Above: Mato (drums) and Jon (seated) during drum tracking. Recognize the space? If so, you are one of the 12 people who saw this cinematic debacle, filmed largely in this very building.

Above: Mato (drums) and Jon (seated) during drum tracking. Recognize the space? If so, you are one of the 12 people who saw this cinematic debacle, filmed largely in this very building.

Several years ago, before I had Gold Coast Recorders, I had a modest recording-studio setup in the former American Fabrics factory on the east side. It was a small operation with a large control room and two small ‘booths’ with observation windows linking all the spaces. Nothing fancy, but I did manage to make a number of successful productions there. NEways… due to the very small size of the tracking rooms I sometimes resorted to tracking after-hours and on weekends in other parts of the floor. A few tracks from one of my final sessions there were recently released.

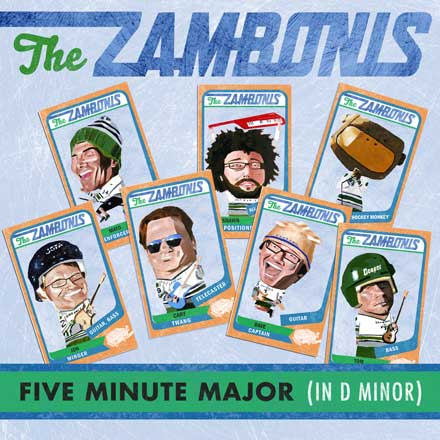

Have a listen to “Brass Bonanza,” the lead-off track from Five Minute Major (In D Minor), the latest album by The Zambonis. The record was released in February 2012 to great response from The New Yorker, The Examiner, and NPR.

Have a listen to “Brass Bonanza,” the lead-off track from Five Minute Major (In D Minor), the latest album by The Zambonis. The record was released in February 2012 to great response from The New Yorker, The Examiner, and NPR.

LISTEN: Brass Bonanza

Horn tracking space for “Brass Bonanza.”

Horn tracking space for “Brass Bonanza.”

I love Pro Tools. I’m not afraid to say it. I love the convenience, the low cost, the rapid editing ability, the fact that it leaves essentially no limits to music production other than the imagination and the skill of the artists/engineer. And while I tend to use plug-ins (audio-processing sub-programs that run within the pro tools software body) for more corrective rather than creative purposes, preferring to ‘get-the-right-sound-on-the-way-in,’ I don’t have many issues with how they sound either. The one thing, the one little thing that I can’t quite fall-in-with, though, is digital reverb.

Back in the ole’ days when I used a Yamaha Rev7 and ADATs I really did not mind the sound of digital reverb; the recording media was lower-resolution, the Rev7 was 12-bit and had much less high-frequency content to begin with, and I was certainly less critical of a listener. In my current set-up of Pro Tools HD3 with Lynx convertors and a properly tuned control room, though, I just can’t seem to fool myself into thinking that the digital reverb plug-ins effectively create the sound of an actual space. Not that this is the only possible function of reverb; reverb is also useful for smoothing out pitch issues and simply creating multiple planes of depth within a sonic field. But when I’m recording a rock band, trying to capture the energy and volume of a performance, I feel like it does the band the most justice to ‘put it in a space.’ And what better space than real space? In the case of ‘Brass Bonanza,’ there was no artificial reverberation used. The drums were tracked in the space that you see them in: approximately 30% of the way along a 100-foot hallway. The horns were tracked in the tiled restroom that you see, with the single ribbon mic depicted in the photo. How much additional value/merit does this give to the recording versus running a reverb plug in? That’s up to you to decide. The band wanted a very reverberant sound and the only way that I can be satisfied with heavy reverb is if it has some if the complexity, texture, and non-linearity that a real space offers.

So what do you do if you don’t have a 100-foot hallway or an 1100-sq ft live room to track drums in? I’ll begin with some advice given to me several years ago by the great producer Martin Bisi. I was subletting studio space from Martin at the time and in one of our many wonderful conversations Martin offered me this bit of wisdom which I paraphrase for you here. Life is complex; reality is complex. What we experience in the world is complex. The more sonic complexity you introduce into a recording, the closer you come to recreating actual lived experience. I hesitate to say “you make it life-like,” since this is ultimately not possible, but you get closer to that impossible goal.

So if this is true, what does it mean for process? Well, first of all, notice that there is no mention here of musical complexity. We’re talking about adding sonic interest to a musical performance. This ultimately holds the promise of allowing us to simplify and streamline the musical lines/performances while still creating and maintaining a huge amount of interest for the listener. With enough detail, care, and complexity achieved in the audio rendering of a musical performance, even the most utterly simple melody, phrase, line, or note can create incredible meaning. This is the most basic, and the most profound, goal of creative audio engineering.

Second, but no less important, is this idea that perhaps it is the complexity of the sonic-event, and not necessarily any verisimilitude to any actual acoustic even/space, that really matters most. So while I may have coveted the sound of that long hallway and that super-reflective restroom, perhaps what I really gain from those sonic generators is the infinite amount of complexity that they bring to the sound, and not necessarily the fact that I think the qualities of actual physical space are accurately described in the mix. Here’s something you can try at home. Create your mix using whatever digital reverb tools you have. Print the output of the reverb as an audio stem. Solo that stem. Find the space in your house/apartment/studio that has the most interesting sonic quality and a pleasing frequency-response character. Put your monitor speakers and a stereo pair of mics in that space and re-amp the reverb stem only. Record that to its own stereo track. You have now added an infinite (within the limitations of the A/D convertors) amount of complexity to a digital reverb that is, necessarily, somewhat limited in detail. See if this new, 2nd-generation reverb adds interest and complexity to the mix. You will probably need to EQ it a bit, but you can do this fairly easily by using the first-generation digital print as a guide. Consider using this 2nd gen reverb as perhaps a ‘spotlight’ reverb for the ld vox, chorus snare drum, or percussion stem. When we re-orient our awareness to the problem/promise of complexity in sound-recordings rather than fidelity, great things can and will happen.

You can learn more about The Zambonis and stream their new record at TheZambonis.com. “Brass Bonanza” and “Fight On The Ice” are my two productions on the record; the rest of the album was produced and engineered by the great Peter Katis and Greg Giorgio at the world-renowned Tarquin Studios, also located in scenic Bridgeport Connecticut.

7 replies on “What do we get from the sound of a space?”

“When we re-orient our awareness to the problem/promise of complexity in sound-recordings rather than fidelity, great things can and will happen.”

Right on. Never said better than that.

thanks man! Good to see you round these parts again… LMK if yr ever back in CT… c.

I’m concerned that this newfound aloofness to fidelity is at least partially because, unlike the people one generally recorded fifty or even thirty years ago, so many “artists” today _can’t play_.

The general technical level of musicianship of people coming into the studios I have done work for is depressing. The singers are terrible. The drummers are terrible.

The guitar players know a lot of licks but they don’t have any comping skills.

And the songwriting skills suck. Really.

The first requirement for recording, to me, is to have something worth recording.

I don’t often comment back on these sort of things, since my views are all readily on display on the 1000+ pages of this blog, but here’s my $.02. What you say may be true of your experiences. That being the case, I have never found there to be any necessary connection between ‘fidelity in the audio-rendering of an artist’s performances’ and their level of skill and/or imagination. For instance: I cannot think of a better Dylan album than the basement tapes. I cannot think of a better 90’s songwriter than Bob Pollard (well, maybe malkamus in his earlier years but it’s all about the same there as far as fidelity). There is a definite limit to the gains that can be made to the quality of a recording through enhancing the fidelity; the uncertainty of the playback apparatus further ensures this. Complexity, the adding of sonic detail in an audio rendering, however, offers limitless potential for new ideas/and direction.

Although I’m not by any means a huge Judy Garland fan, I thought the remastered Garland Carnegie Hall album a few years back was, bar none, the most impressive thing I’d heard in years. The backstage jabber you hear before the intro was so realistic, and so detailed, and so correct sounding I actually got up and looked around the room.

It was complex, but it was a complex rendition of reality. That’s impressive.

I think the reason songwriting skills are so bad, is that no one today has to have the kind of English composition skills which were required years ago to graduate high school .

People have no concept as to sentence structure, don’t know what assonance or alliteration are, and have never hears of a thesaurus, let alone a rhyming dictionary, the best of which were the secret weapons of many of the old timers.

Now, a recording artist has to be a performer, a lyricist, a composer, a business person and more and more an engineer/producer. Technically, things were better in the old days, because except for Les Paul no one was more than one or two of those. And few of us could do that many things that well. Something, usually everything suffers.

You really (usually) can’t have it all. I’d rather be a success at one thing than at none, and all too often in our modern world that’s what happens.