Download a seven-page scan of some interesting hardware on offer in “Making 4-Track Music,” Track Publishing 1987:

Download a seven-page scan of some interesting hardware on offer in “Making 4-Track Music,” Track Publishing 1987:

DOWNLOAD: 4trackMusic_JohnPeel

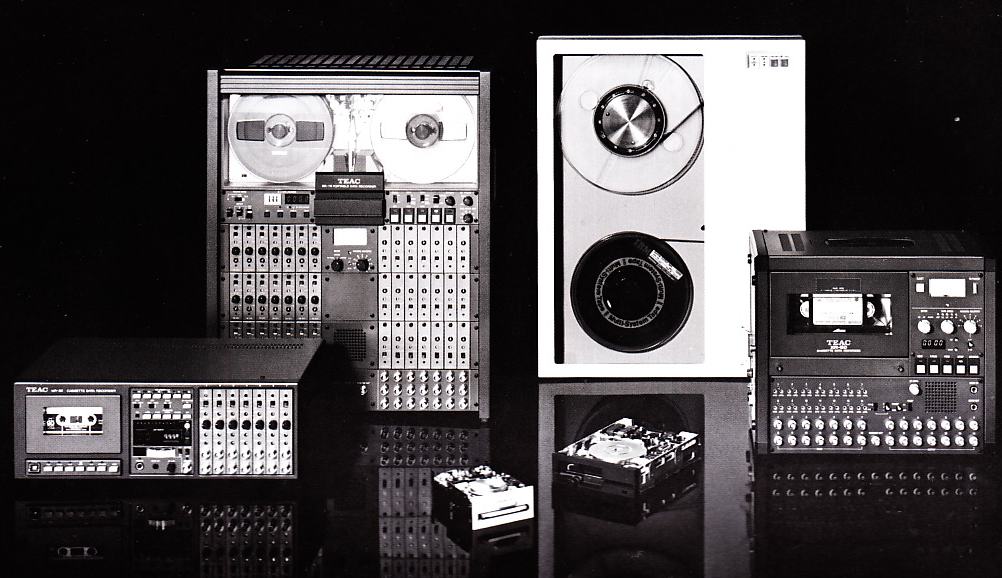

Includes advertisements for Yamaha MT2X, DX100, and RX17 drum machine; Akai MG614 four-track machine, Tascam Porta2 4-track, Fostex 160, the Boss Micro-Rack series (RDD-20 delay, RPS-10 pitch shifter, RCL-10 compressor, RRV-10 reverb, plus a ton more), and KORG’s multieffects.

*******

***

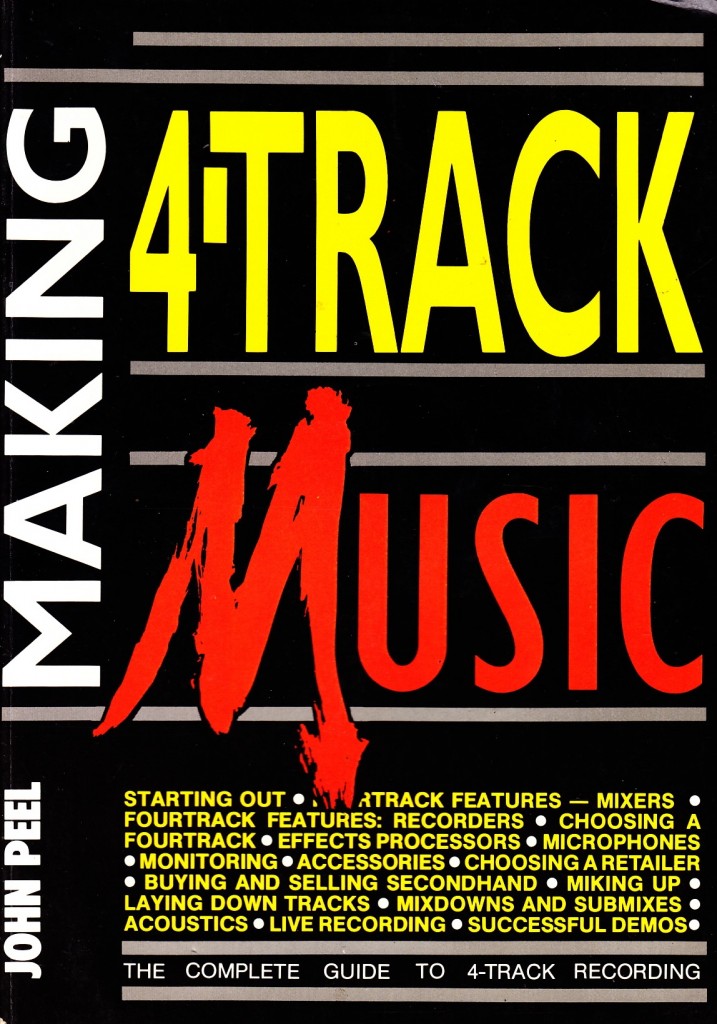

First-things-first: I have no idea if the ‘John Peel’ to whom this book is credited is the John Peel, he of legendary status as a DJ and taste-maker for an entire generation of rock and pop music. There is nothing whatsoever in this 98pp paperback volume (found in a Manchester OXFAM back in the early 00’s) that offers any indication pro or con. A third option would seem to be the ghostwriter scenario. Anyhow. “Making 4-Track Music” (h.f. “M4TM”) is an A5-sized paperback that attempts to introduce readers to the equipment and processes of using 4-track recorders.

The 4-track recorder, for those unfamiliar, is a category of product first introduced by the TASCAM corporation in 1979 with their model 144.

The 1979 TASCAM 144. Bruce Springsteen recorded his greatest album on this small plastic machine, believe-it-or-not. (Image source)

The 1979 TASCAM 144. Bruce Springsteen recorded his greatest album on this small plastic machine, believe-it-or-not. (Image source)

TASCAM already dominated the home-recording market with their 3440 1/4″ open reel tape recorder and the associated mixer-units that were marketed alongside it. These systems had a rather high cost of entry, though: they cost much more than a good used car. The 144 brought the basic concept of multi-track audio recording and mixing to a far lower price-point by using consumer cassette tape rather than 1/4″ open reel tape as the recording media, and by combining the audio-recording device and the audio-mixing apparatus into one single item. This made for a much more affordable system and it also made for easier use: no wires to hook up, no redundant or unnecessary features. Just the basic technology needed to record a performance and then add 3 additional performances in perfect synchronization while retaining the ability to control relative volumes and treatments of each track. With a creative user, the 4-track machine is capable of much more, but this is the basic concept.

“M4TM” covers all of this, and more; there is an explanation of the various recording and mixing features that the consumer would encounter in the marketplace, plus good treatment of the various types of additional processing equipment that a 4-track owner might like: digital time-based effects (delay, etc), compressors, gates, EQs., etc.

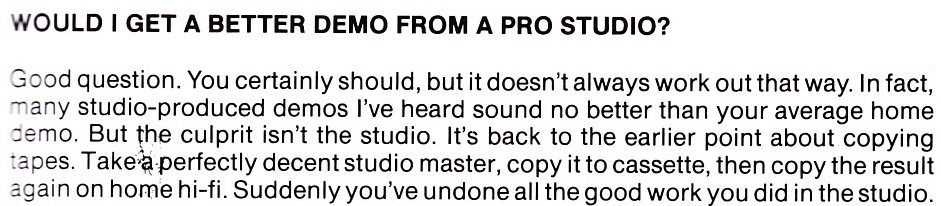

The aesthetics/art of making recordings is not really considered at all; there is a lot of talk about money, costs, (e.g., KORG’s above-depicted rainmaking) and the improved ‘recording quality’ that such expenditures can deliver but no mention of improving the presentation of songs and sonic ideas via any of this technology. Here’s a typical passage:

The aesthetics/art of making recordings is not really considered at all; there is a lot of talk about money, costs, (e.g., KORG’s above-depicted rainmaking) and the improved ‘recording quality’ that such expenditures can deliver but no mention of improving the presentation of songs and sonic ideas via any of this technology. Here’s a typical passage:

As someone who’s work is largely based on the commercial recording studio that I own and operate, I find it rather… alarming/offensive that the prime benefit of making a recording in a pro studio is the sound-quality, to extent that this benefit could be completely undone by several generations of tape-duplication. Jesus. I like to hope that I give my clients something more than a good signal-noise ratio and even frequency response. The passage above kind of makes it seem like it’s the EQUIPMENT in a studio that is doing the work, rather than the engineer… is this how most musicians feel about studios? Is this how I used to feel about studios, when I was 4-tracking at home at age 19?

(me at home, age 19: via Tascam Porta 03, Boss Micro -Rack effects): 07 The End

Furthermore, M4TM does not even entertain the aesthetic or artistic possibilities of all of this ‘4-track’ equipment. Rather, the emphasis is very much on ‘making-a-demo’ en route to possibly getting a ‘record deal,’ and all that this will entail (presumably the “Riches and Fame” for which you will have KORG to thank). The idea of possibly creating a compelling piece of artwork with this equipment is simply absent.

I wonder when this changed. By the time I started recording heavily on a four 4-track machine, a mere 8 years later (1995), musicians like Bill Callahan (aka SMOG) and Jeff Mangum (aka Neutral Milk Hotel) were already getting attention specifically as masters of 4-track recording. These guys did not appear too interested in making a ‘real record’ in a ‘pro studio.’ The 4-track medium, with its attendant tape hiss, awkward usage once you went past four tracks, and total absence of any sort of editing ability, was a huge part of the artwork that they created. Artwork that has truly endured.

I went to see Jeff Mangum perform last week here in CT. He did a solo set at the Shubert Theatre in New Haven. Jeff Mangum has not released a major album of his own in 13 years. The Shubert was nearly sold-out to it’s 1591 capacity.

Have a listen (above) to “Naomi” from Neutral Milk Hotel’s 1996 4-track masterpiece “On Avery Island.” Would these songs have been rendered any more compelling had they been tracked and mixed in a studio? I think we all know the answer to that… Ultimately, though, what Mangum’s solo-acoustic-gtr-and-voice performance at the Shubert last week demonstrated to me was more the fact that it probably honestly didn’t matter how he had made those seminal recordings: the songs themselves are so good and his voice and affect are so well-wrought that their properties can impress regardless of the presentation.

Perhaps I am reading into this all too much…perhaps my ideas and taste are a bit ‘off’ and therefore I have ‘niche’ values. Mangum seems, to me, to be a very straightforward singer/songwriter.. but perhaps my appreciation for artists like Jeff Mangum simply indicates that I have ‘weird’ taste, that I am out-of-step with ‘mainstream’ values… Goggle seems to think so. Here’s what you will see if you play a Neutral Milk Hotel song on Youtube:

Is your significant-other cheating on you? Maybe you need to lose those glasses: improve yr appeal? Fuck it, man, you’re a GEEK. Face it. Geek geek geek. Date another geek.

Is your significant-other cheating on you? Maybe you need to lose those glasses: improve yr appeal? Fuck it, man, you’re a GEEK. Face it. Geek geek geek. Date another geek.

I am so confused.

1987/2012: Maybe our John Peel simply wrote “M4TM” in a lost era, simple as that… an era when there still was a vigorous economic basis for the music-recording-industry and therefore the idea of recording music as INDUSTRY rather than EXPLOIT was still the dominant theme. It’s also interesting to consider that around the time of the first Neutral Milk Hotel album we also saw the introduction of Tape Op magazine, the first (that I am aware of…) widely-distributed publication that embraced the ethos of home-recording as a serious art form. And all of this happened just-in-time for the introduction of the first affordable DAWs (e.g., Pro Tools LE), which completely changed both the technique and the aesthetics of audio recording forever. You still need to be able to write a good song though. That much hasn’t changed.

Previous 4-track coverage on PS dot com: