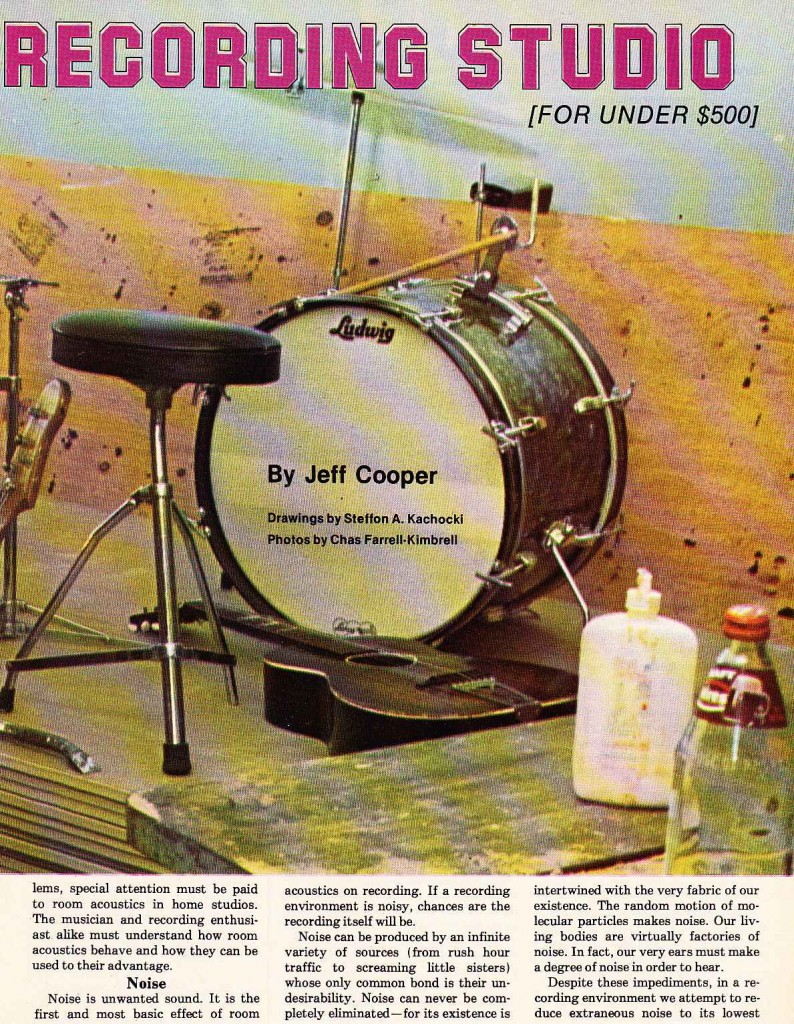

Decided to build a recording studio. It won’t cost me a ton of bread.

Decided to build a recording studio. It won’t cost me a ton of bread.

I heard that it’s important to have a private, personal space to ‘work out ideas’ etc.

I heard that it’s important to have a private, personal space to ‘work out ideas’ etc.

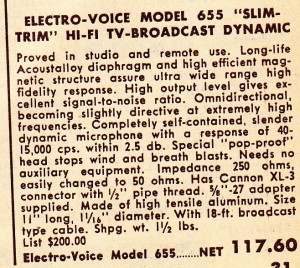

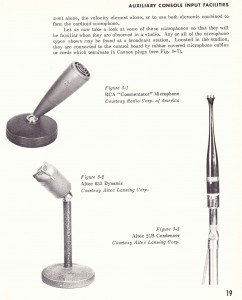

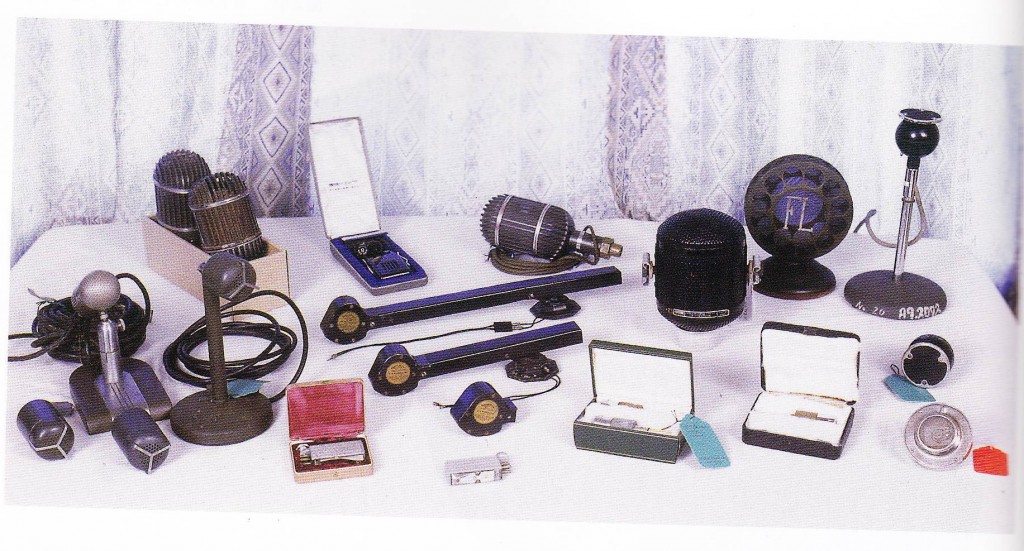

I’ve been reading up on where to stick the microphones. So many loud noises.

I’ve been reading up on where to stick the microphones. So many loud noises.

This shit is hella confusing tho. Might have to go to special recording school/camp.

This shit is hella confusing tho. Might have to go to special recording school/camp.

***********

*******

***

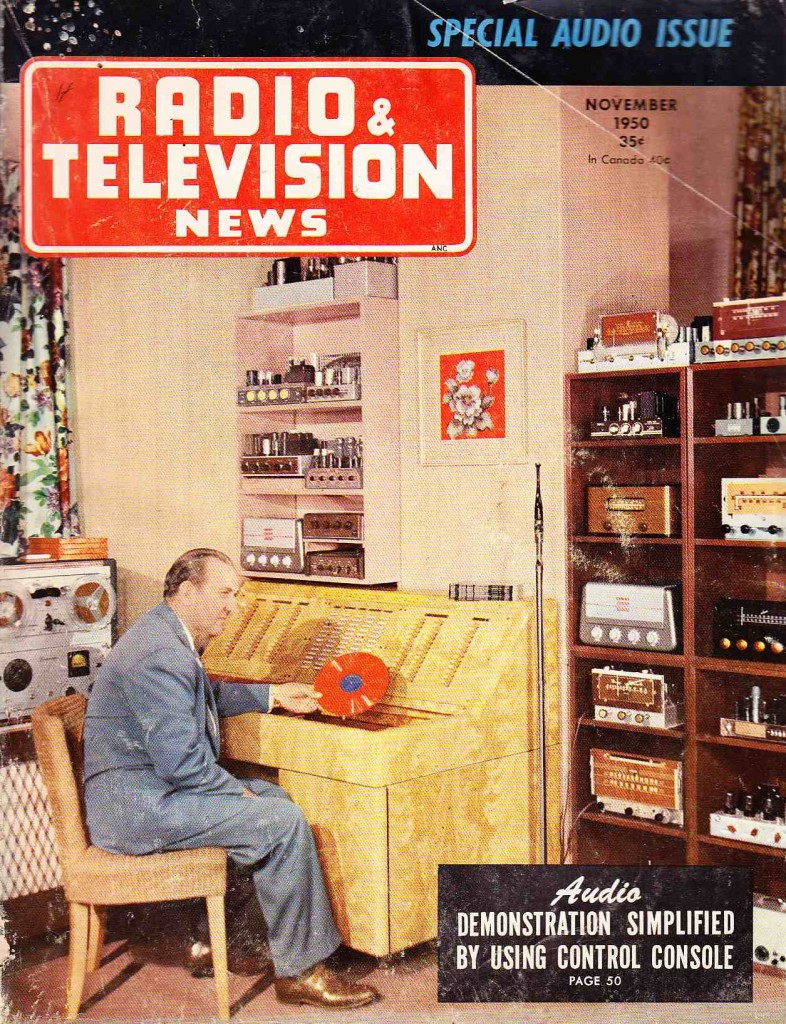

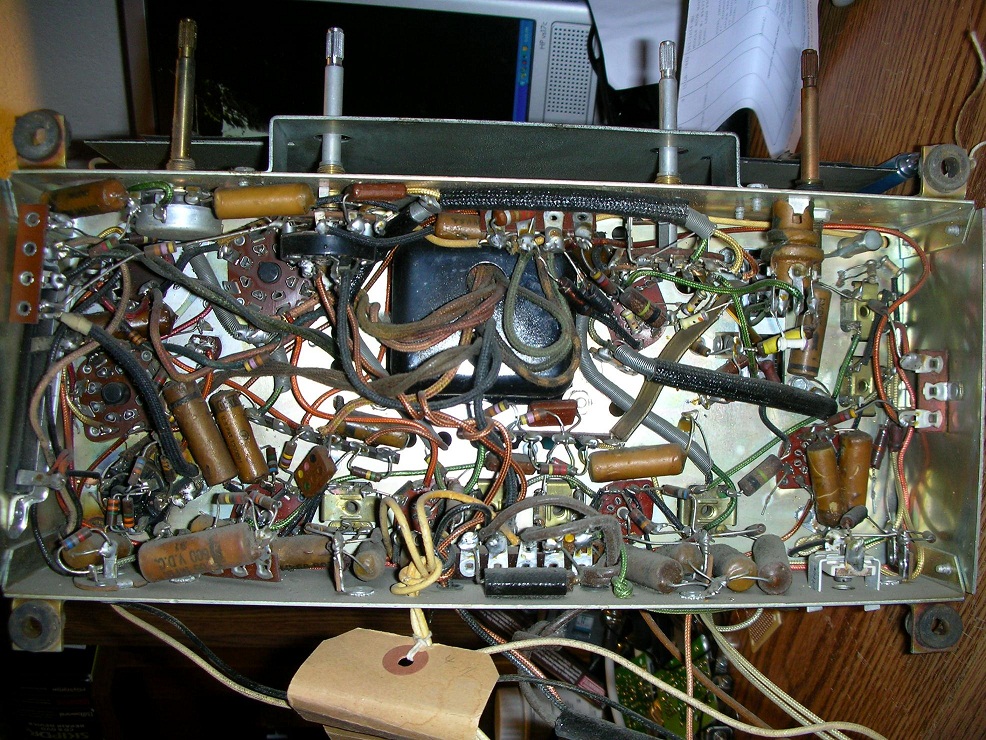

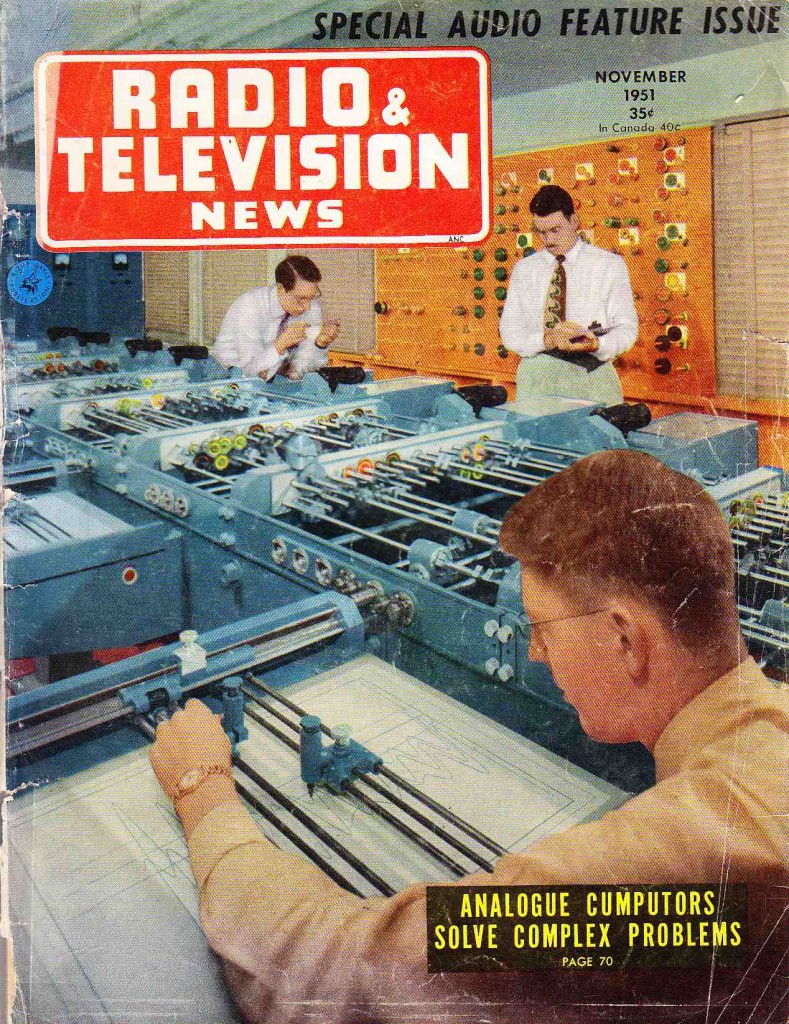

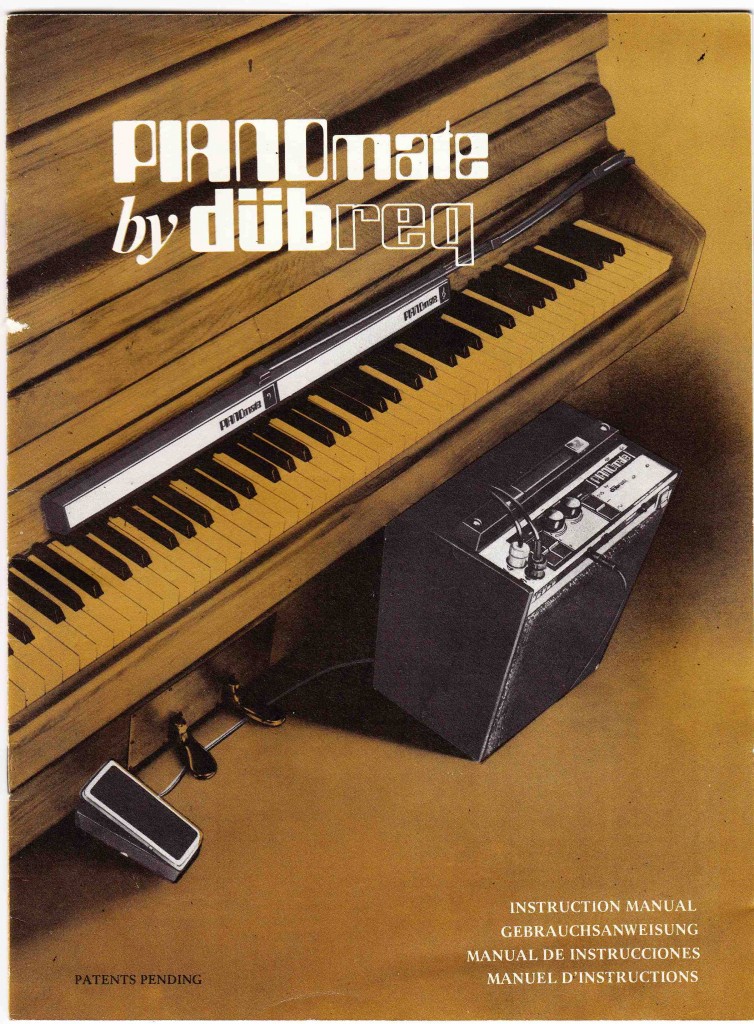

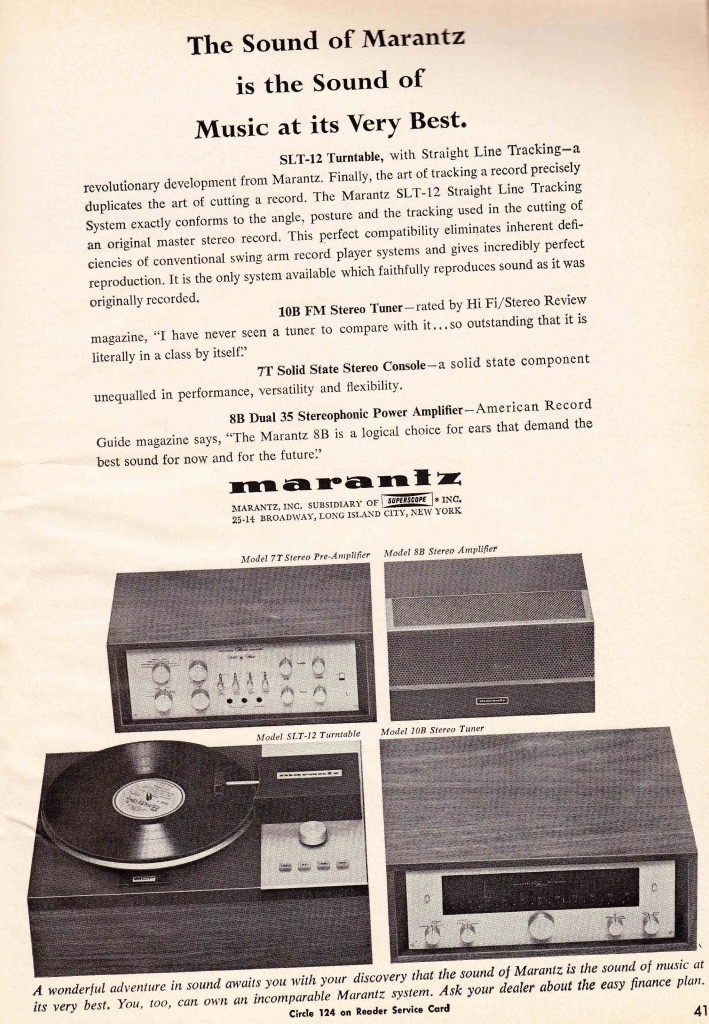

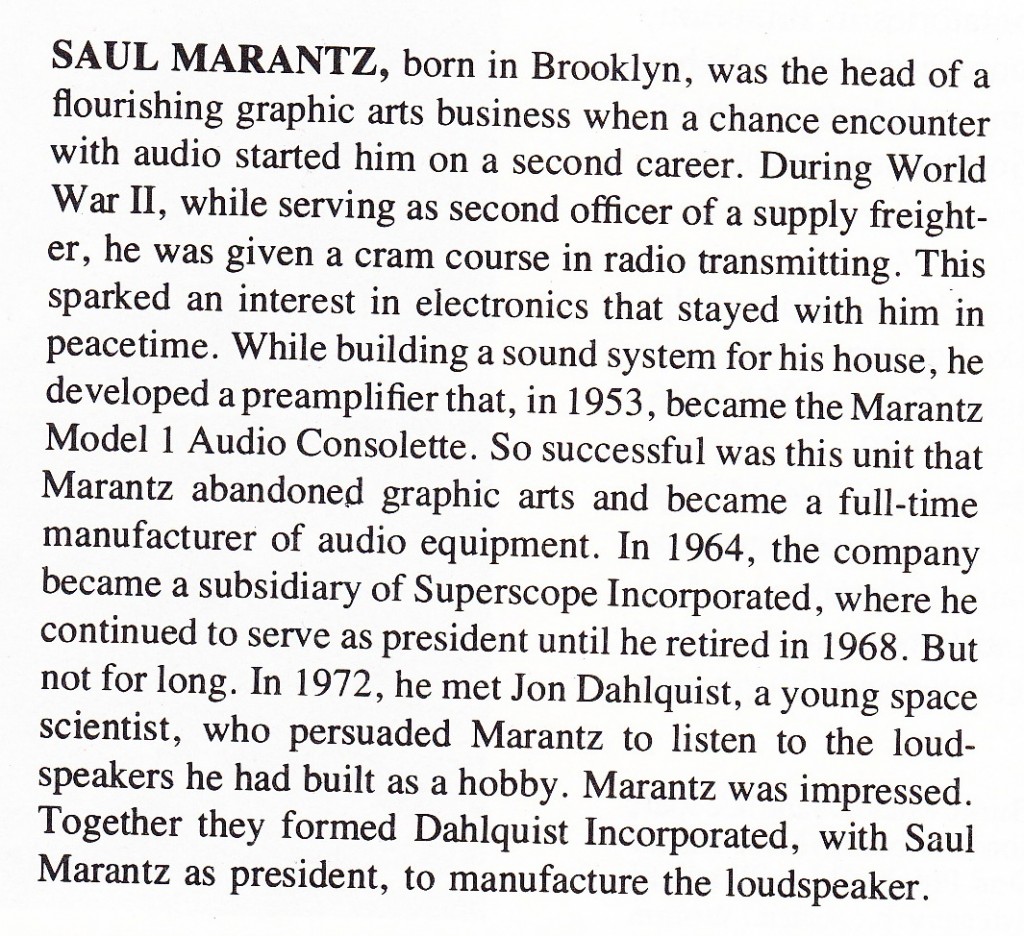

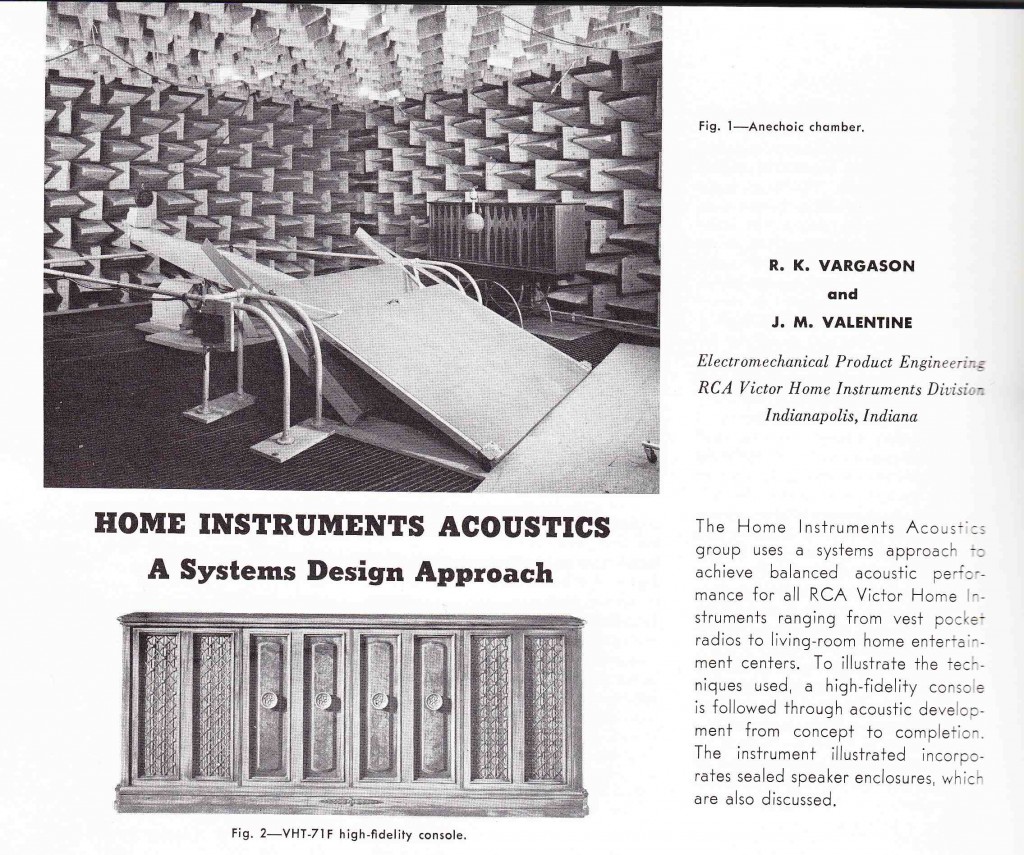

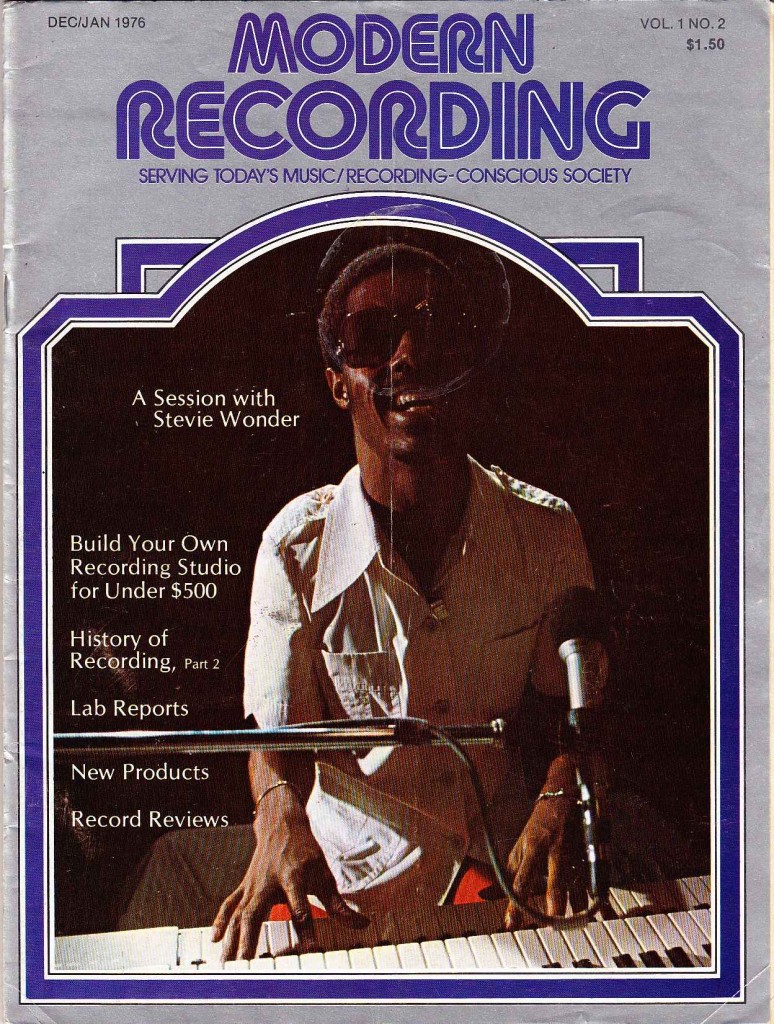

“Modern Recording Magazine” was published from at least 1975 through 1981. This is all I can confirm from both the internet, and from my own digging through physical copies of the magazine. Based on the content of the advertising and editorial, the publication seems clearly aimed at the new species of ‘home-recordists’ birthed by the advent of the TEAC/TASCAM multi-track recording equipment (see scan at head of this article). There is a lot of discussion of tape stock, graphic EQs, where to stick the mics, what goes down in a ‘pro session,’ etc. Unlike “Recording Engineer/Producer,” another publication of the era, this magazine was not aimed at working professional sound engineers. There is plenty of interesting content, though. For instance, well-known music writers Nat Hentoff and Craig Anderton contributed some pieces.

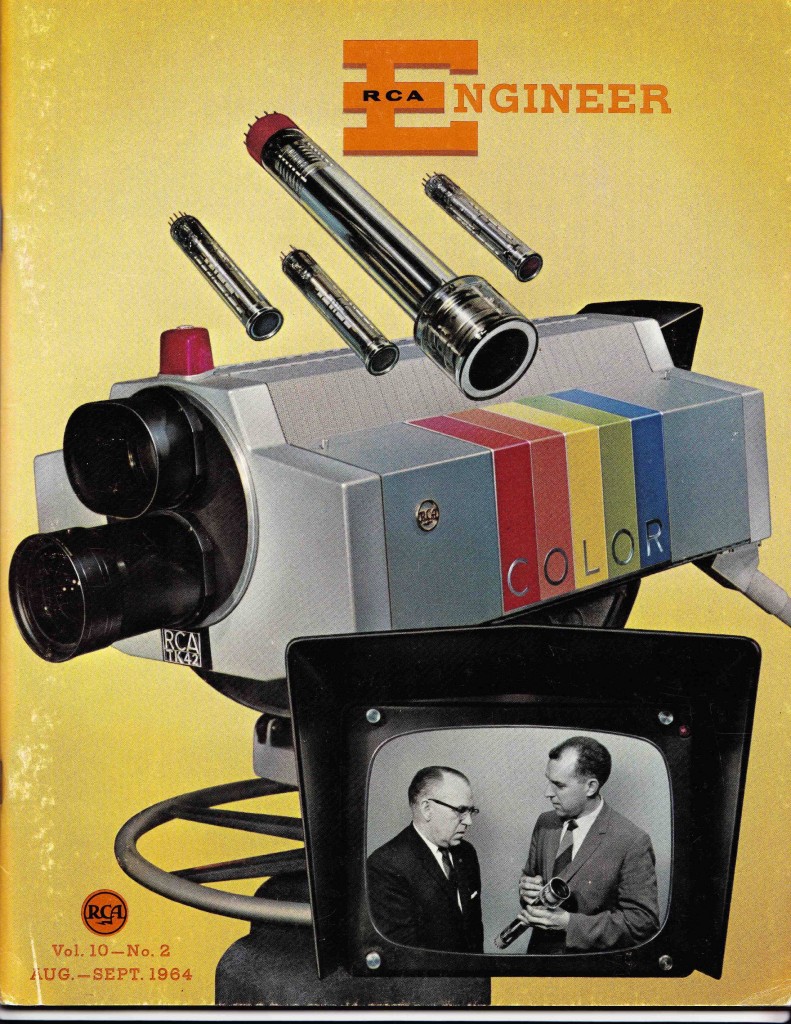

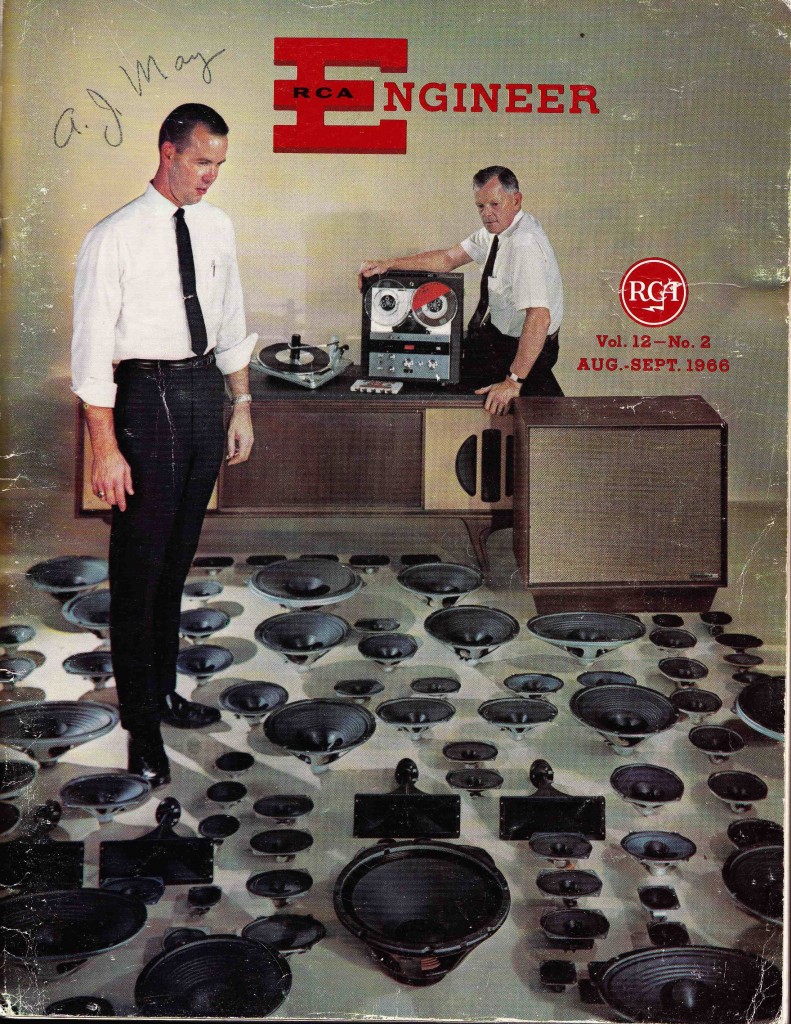

“Modern Recording Magazine” was published from at least 1975 through 1981. This is all I can confirm from both the internet, and from my own digging through physical copies of the magazine. Based on the content of the advertising and editorial, the publication seems clearly aimed at the new species of ‘home-recordists’ birthed by the advent of the TEAC/TASCAM multi-track recording equipment (see scan at head of this article). There is a lot of discussion of tape stock, graphic EQs, where to stick the mics, what goes down in a ‘pro session,’ etc. Unlike “Recording Engineer/Producer,” another publication of the era, this magazine was not aimed at working professional sound engineers. There is plenty of interesting content, though. For instance, well-known music writers Nat Hentoff and Craig Anderton contributed some pieces.

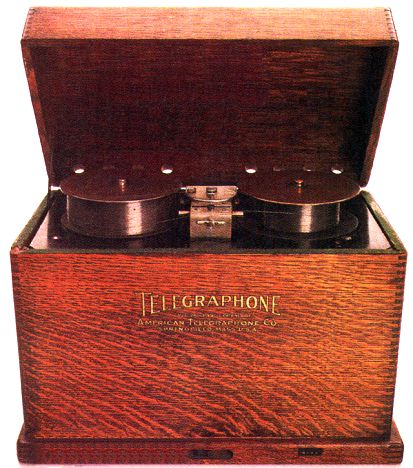

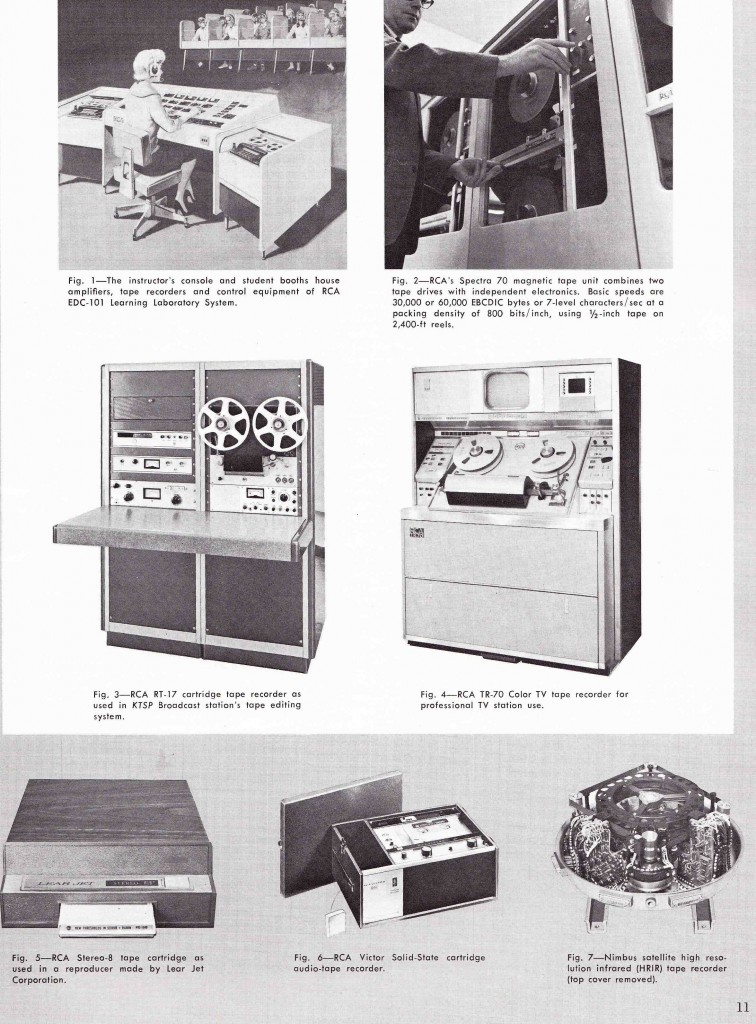

The Jan’76 issue which I read today featured “Part II” of “The History of Magnetic Recording” by a Robert Angus. This article revealed that the earliest magnetic audio recorders were demonstrated in the year 1900 and marketed and sold in the United States as early as 1908. Goddamn that is a long time ago. A young Danish engineer named Poulsen patented the idea in the US around that time. For all the details about Poulsen and his predecessors, visit this page.

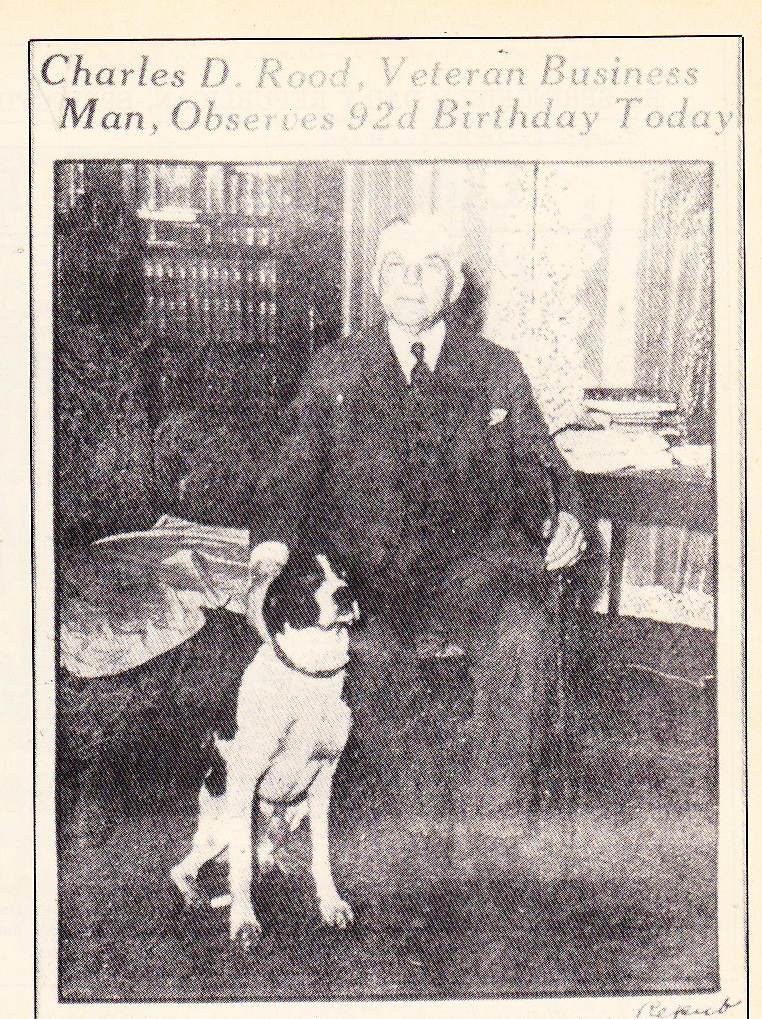

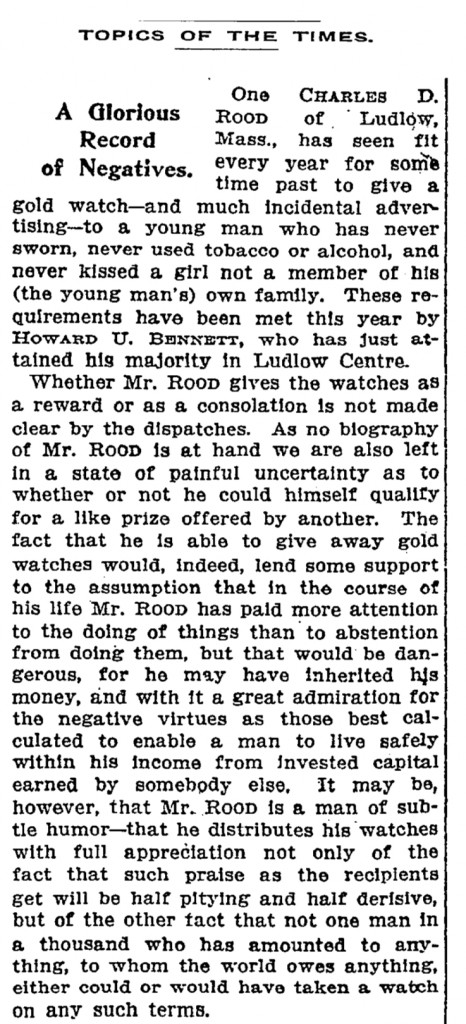

The earliest champion of magnetic recording in the United States was Charles D Rood, pictured above on the eve of his 92nd birthday. Rood was the archetype of the 19th century plutocrat: he made his career as an oil salesman, made his millions popularizing the Hamilton watch, and then lost it all trying to manufacture recording equipment. He was a character of mixed-reputation; here the NYT lampoons him in an article from 1911:

The earliest champion of magnetic recording in the United States was Charles D Rood, pictured above on the eve of his 92nd birthday. Rood was the archetype of the 19th century plutocrat: he made his career as an oil salesman, made his millions popularizing the Hamilton watch, and then lost it all trying to manufacture recording equipment. He was a character of mixed-reputation; here the NYT lampoons him in an article from 1911:

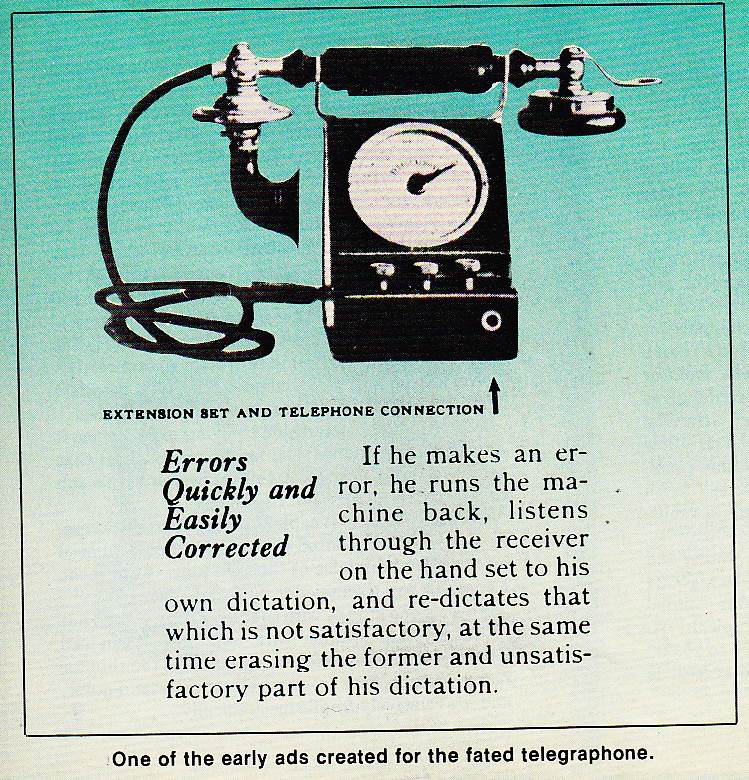

Poulsen/Rood’s Telegraphone was the earliest mass-marketed Wire Recorder, a recording device which works pretty much the same way as a tape recorder, but with a piece of magnetic wire in place of metal-coated tape.

Poulsen/Rood’s Telegraphone was the earliest mass-marketed Wire Recorder, a recording device which works pretty much the same way as a tape recorder, but with a piece of magnetic wire in place of metal-coated tape.

These machines were not intended to record music. Given that (as the NYT article tells us) Rood hated smoking, drinking, cussing, and cavorting, I think we can fairly assume that he was not too much into music. What Rood was into, clearly, was business: and the Telegraphone was created and sold as a business dictation machine, designed to be used with a telephone as the input device.

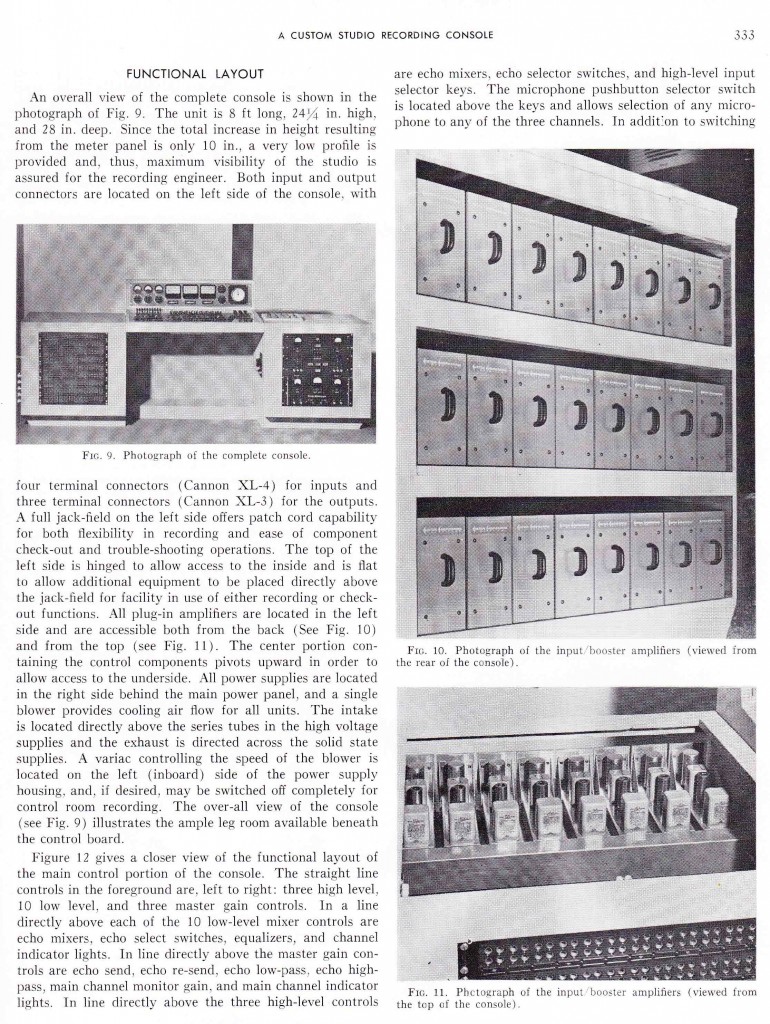

According to Angus’ article in “Modern Recording,” Rood seems to have turned down or ignored every possibility to promote, exploit, and grow the technology that he was manufacturing; instead, he seems to have devoted his energies towards stock manipulation, lawsuits with AT&T, and selling equipment to the German Navy (in the 1930s….). Rood even ignored Lee De Forest’s experiments using the Telegraphone for use in sync with Motion Pictures. In 1912. This is a full 15 years before “The Jazz Singer” debuted. BTW, if you are not familiar with Lee De Forest: He invented the vacuum tube.

If anyone has ever used a Telegraphone, drop a line and tell us about it.