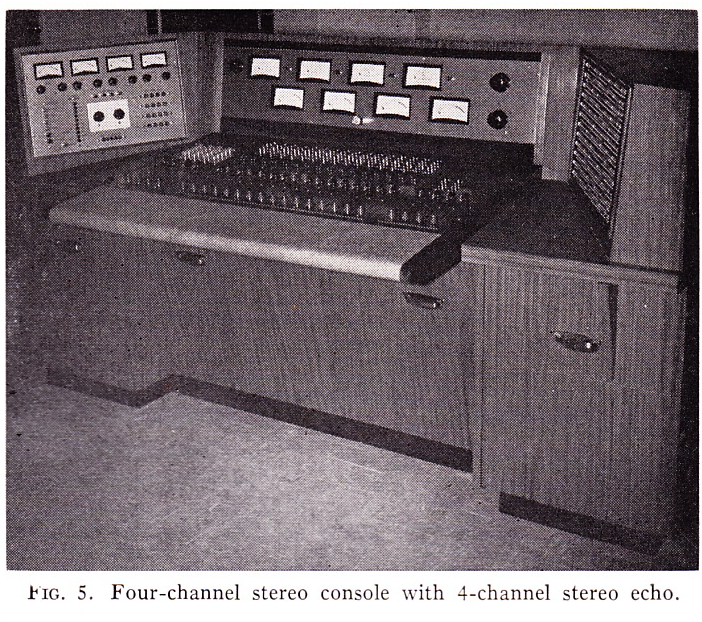

Above: 12×3 Audiofax mixing desk circa 1961.

Above: 12×3 Audiofax mixing desk circa 1961.

I was reading a 1961 AES journal when I came across this piece by Phillip Erhorn of Audiofax associates in which he details “New trends in stereo recording consoles.” Erhorn will let you have your channel EQs and compressors, but only very begrudgingly.

Here’s Erhorn describing how he feels the trend for extensive channel EQ developed:

I mean, yeah, I agree, many condenser mics are hyped in the high end. But why the hostility, buddy? Oh and about all those channel compressors?

I mean, yeah, I agree, many condenser mics are hyped in the high end. But why the hostility, buddy? Oh and about all those channel compressors?

Remember what I said a few posts back about The Pre Rock Era? How long did it take for our culture to shake off the idea that ‘verisimilitude to an actual acoustic event is the fundamental function of audio’? I’ll remind you that in only about 3 years’ time, EMI staff engineers would be pushing their modded’ Altec compressors hard to get the sounds that helped create the Beatles’ success. Oh the times they are a’changing.

Remember what I said a few posts back about The Pre Rock Era? How long did it take for our culture to shake off the idea that ‘verisimilitude to an actual acoustic event is the fundamental function of audio’? I’ll remind you that in only about 3 years’ time, EMI staff engineers would be pushing their modded’ Altec compressors hard to get the sounds that helped create the Beatles’ success. Oh the times they are a’changing.

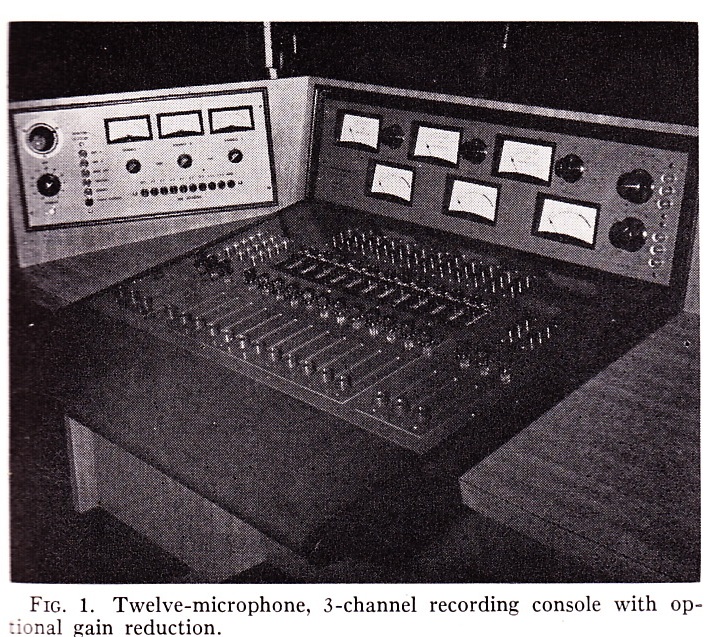

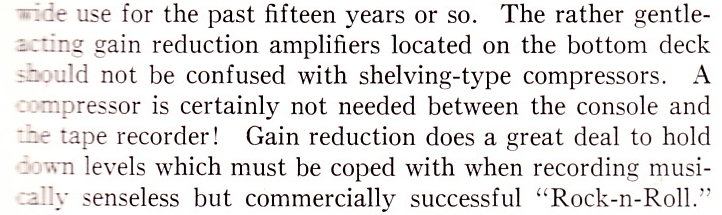

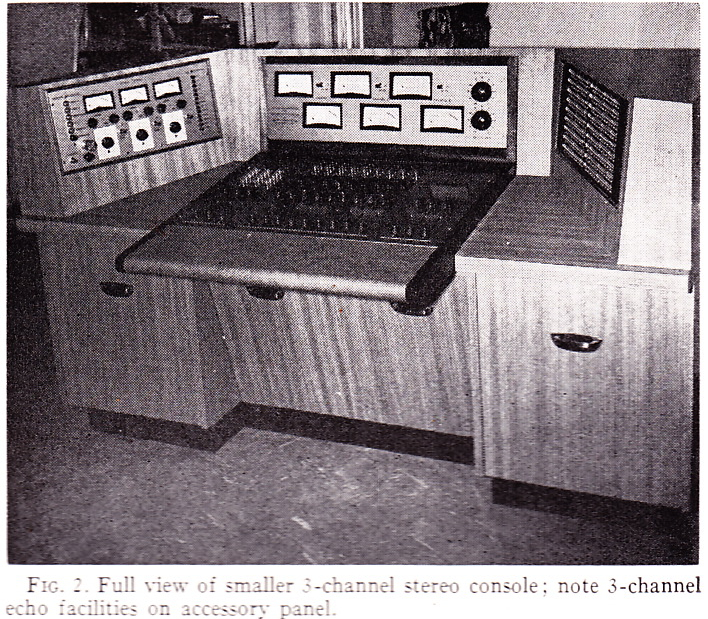

Let’s get back to those swell-looking Audifax consoles tho…

Above, the same 12×3 desk, inside and out. What a work of art this thing is! Someday. I . Will. Build. My. Own. Console.

Above, the same 12×3 desk, inside and out. What a work of art this thing is! Someday. I . Will. Build. My. Own. Console.

************

*******

***

I am going to take a bit of a left turn here. Not exactly like Jung’s Left Hand Path but… Let’s get back to the hostility towards this new idea of audio-as-sound-modification-technology (as opposed to documentation-technology) that we read in the passages above. Erhorn was/is obvs a very talented man who cared deeply about music or he would not have gained the skills/drive to construct the intricate pieces we see above. So his views can’t just be written off. Which begs the question: If Erhorn’s views as an accomplished audio professional were, in 1961, slated for imminent obsolescence, then which of our current paradigms are headed for the dustbin? I don’t think the answer has anything to do with fidelity or even any particular kind of recording technology, necessarily. In 1961, the history of audio trends was simply an upward vector. Higher fidelity was ‘better.’ Frequency response and distortion % was always getting ‘better.’ Progress towards increased fidelity was the paradigm, and any deviation from this progress (such as the need to ‘EQ’ a mic to achieve a supposed marketing prerogative or the need to compress a loud, ‘music-less’ but sale-able band of youths) was bad, right?

Well, the ‘fidelity problem’ was pretty much solved by the late 1970s… the high-end of professional and consumer equipment available at that time is as close-to-perfect, in terms of sheer audio performance, as any user is likely to need. Which is why the manufacturers turned towards the convenience problem instead. This brought us the Walkman, the CD, and ultimately, the MP3. So with the ‘fidelity problem’ solved, and all of our attention now collectively focused on the ‘convenience problem,’ we abandonded the paradigm of the upward vector of fidelity and instead enter an age of fidelity-trends. High-fidelity sounds are in vogue for a while; and them low-fi and distorted sounds become popular. We then tire of the low-fi and artists start making slick-sounding records again. Etc., etc. Now, there are real moments in the culture that precipitate each of these shifts, but the pattern seems likely to keep repeating. The point is: neither hi-fi nor low-fi are going anywhere. We now have a plurality of acceptable approaches to the generation of recorded musical performances. So what’s to obselecse then? Which viewpoint is about to become hopelessly outdated?

It’s my current feeling that the answer has something to do with copyright, ownership, and fair use. Not fidelity, not any particular recording technology, but copyright and the idea of what kind of ‘use’ of existing recorded materials constitutes a valid new work. I really get the sense from younger artists, as well as my students, that existing recordings — audio-masters made and paid for by other people — are fair game for use in their own productions: no credit or compensation necessary. Of course ‘sampling’ occurred in hip hop for ten years before rap artists had to start paying fees to use recognizable samples in their tracks, but I am more talking about the newer trend of simply lifting an obscure existing song, performing some tweaks on it, and calling it your own production. And maybe it is! Who is to say, really. And that’s kind of the point I am trying to make. If you are a young contemporary musician, what is the material that you work with? What are the compositional elements that you are concerned with? It is the notes E2 – E6 on an electric guitar? Or is anything and everything that you can download for free from the internet? If you want some concrete examples of the kind of music that I am talking about, check out this thread on Hipster Runoff. If you are unfamiliar with HRO, the tone might take a little getting used-to, but the musical examples that the author presents are very valid. Listen to the tracks. Be aware that these are some of the most popular, most relevant rock-music acts in the world today. And ask yrself: how do you feel about this? Can you accept the paradigm shift that is emerging? Can you appreciate that this paradigm shift is taking place at the precise moment that the economic base of the century-old Recording Industry is almost fully collapsed? And while you are pondering that, recall the Marxist relation between base and superstructure, this idea that economic conditions necessarily construct cultural conditions?

Here’s those free music-production apps you asked for. Now go… make some music.