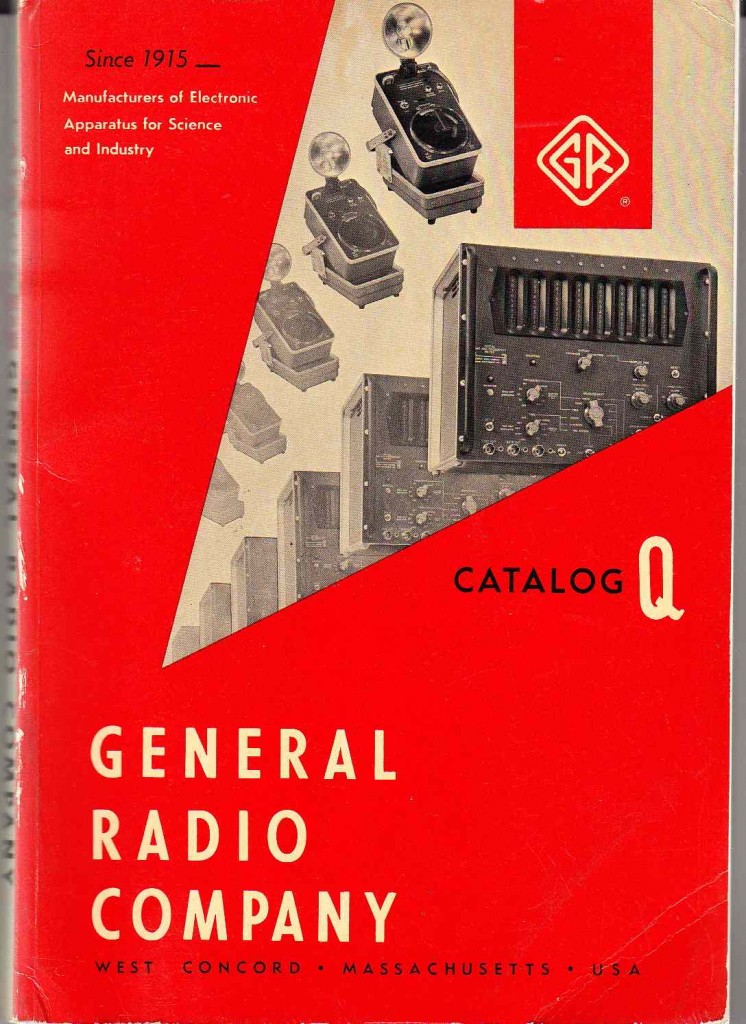

So. 5 years later. 1981. How had ‘home-recording’ coverage changed? The range of products had increased, certainly. There is still a focus here on consumer and prosumer tape decks and tape stock, vague ‘reader-questions’ such as “what does a producer do,” and of course the Teddy-Pendergrass tracking session notes. The publication does seem to have gotten more sophisticated though. We now see ads for expensive test equipment and console automation. Let’s take a look at some of the more interesting bits and bobs c. ’81.

So. 5 years later. 1981. How had ‘home-recording’ coverage changed? The range of products had increased, certainly. There is still a focus here on consumer and prosumer tape decks and tape stock, vague ‘reader-questions’ such as “what does a producer do,” and of course the Teddy-Pendergrass tracking session notes. The publication does seem to have gotten more sophisticated though. We now see ads for expensive test equipment and console automation. Let’s take a look at some of the more interesting bits and bobs c. ’81.

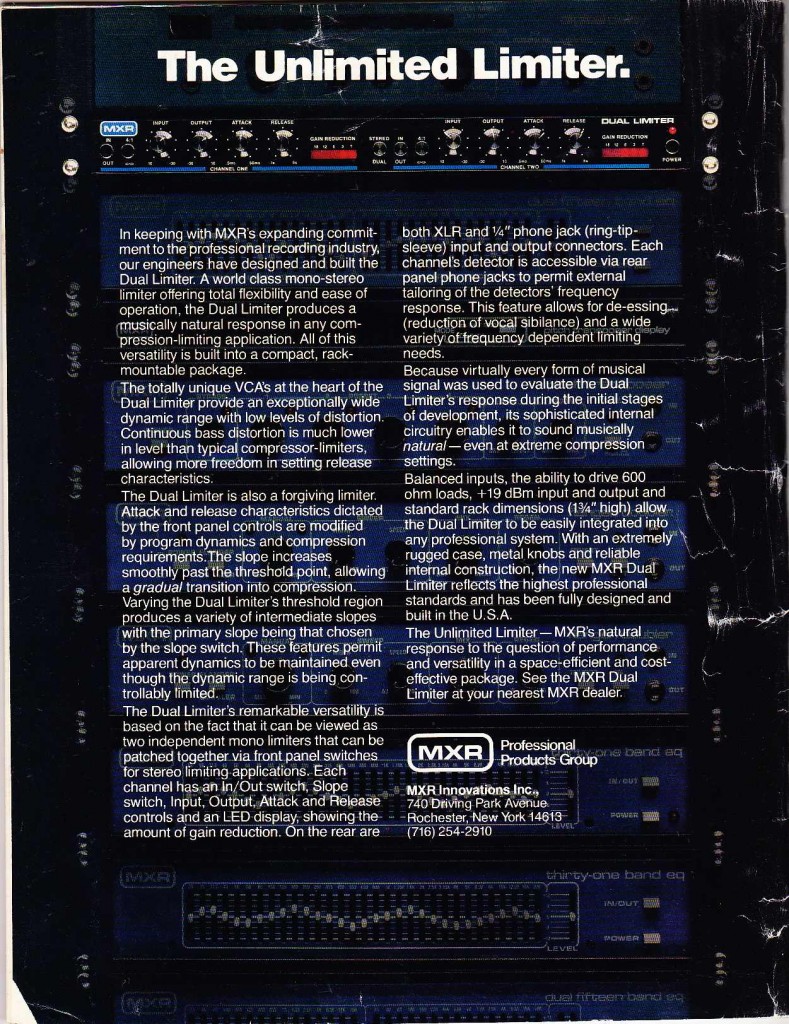

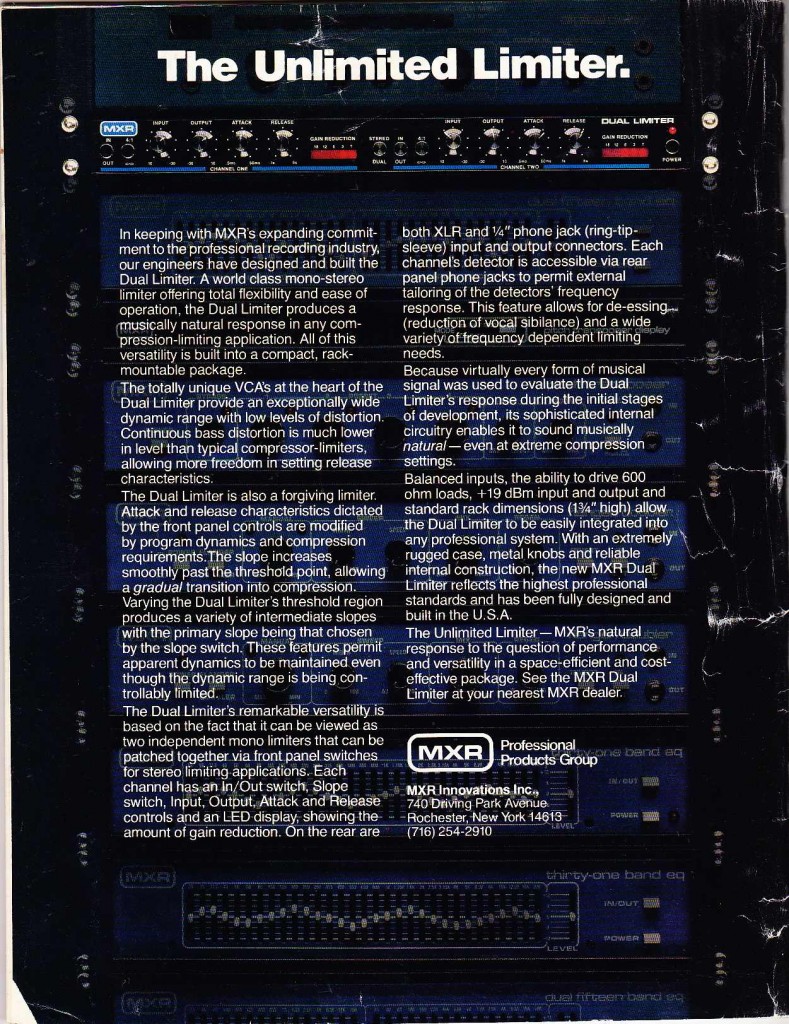

I have one of these MXR limiters. They can be purchased for under $100. Initially I used it often to group-compress drums together with bass for hip hop tracks; lately I’ve been using it for parallel drum compression and it works great for that. Very aggressive sound; quiet, good fidelity. The ‘channel-link’ button seems to do very little; also the input (or output?) gain is not matched between the channels; annoying to work around but it’s worth the hassles for the sound. Pick one up if you can.

I have one of these MXR limiters. They can be purchased for under $100. Initially I used it often to group-compress drums together with bass for hip hop tracks; lately I’ve been using it for parallel drum compression and it works great for that. Very aggressive sound; quiet, good fidelity. The ‘channel-link’ button seems to do very little; also the input (or output?) gain is not matched between the channels; annoying to work around but it’s worth the hassles for the sound. Pick one up if you can.

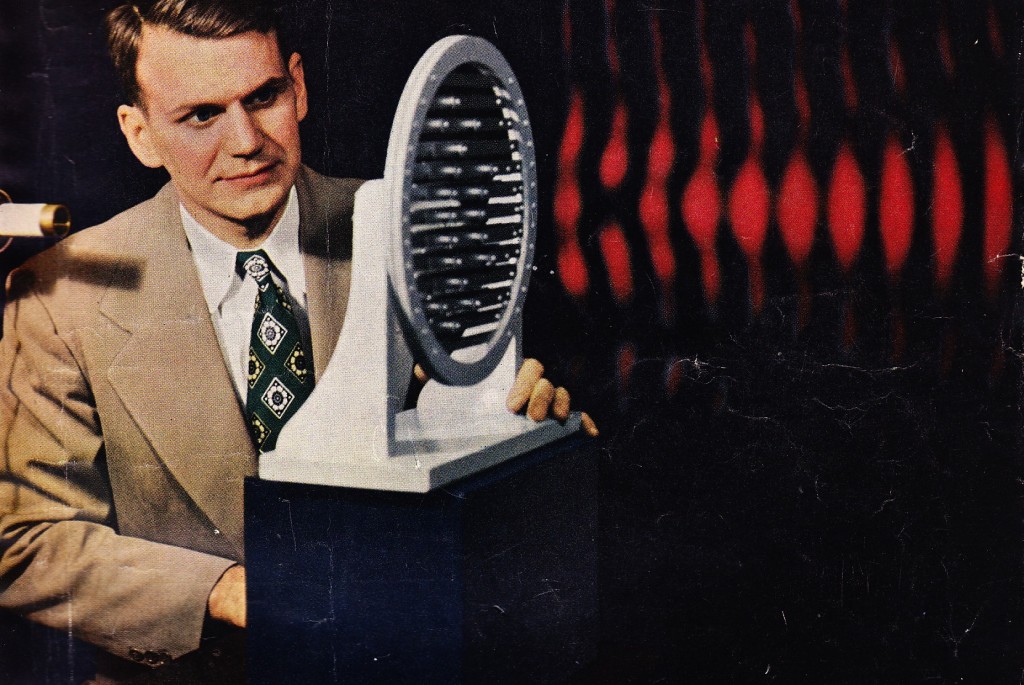

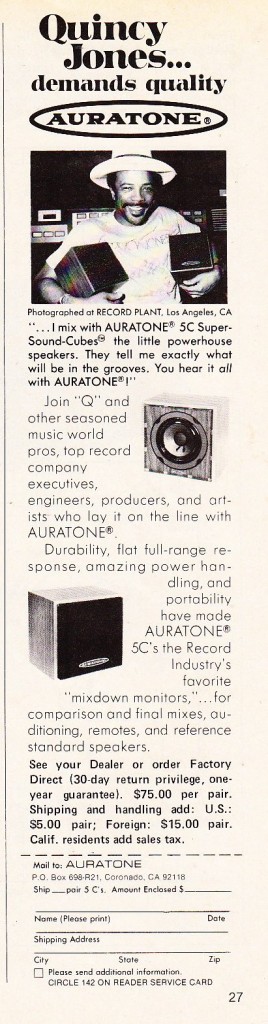

Q is right to demand his Auratones.  This is a truly great product. I had an old banged-up pair for years, and about 5 years ago I put a newly-manufactured pair of “Avantones” in their place. The Avantone is just as good, if not better. What are these speakers and why are they so good? First off, don’t believe the language in this ad. These speakers do not sound great, and they CERTAINLY do not give a mixer “all that will be in the grooves.” These speakers are ‘real-world reference speakers.’ Unlike big, expensive ‘Studio Monitors,’ Auratones/Avantones have no low end and no high end. They sound, instead, like the majority of actual speakers that normal people will actually hear your work on. This is crucial to mixing. In the audio-post-production (IE,. sound work for video mediums) world we call these ‘TV speakers.” As-in, ‘hey charlie, lemme hear it on the TV speakers.’ As-in, Auratones/Avantones sound pretty similar to the speakers that are built in to a decent TV set. But: even better: they can handle very high power. If you need to, you can put pretty heavy watts into these guys (well, at least the Avantones) and you will not damage them.

This is a truly great product. I had an old banged-up pair for years, and about 5 years ago I put a newly-manufactured pair of “Avantones” in their place. The Avantone is just as good, if not better. What are these speakers and why are they so good? First off, don’t believe the language in this ad. These speakers do not sound great, and they CERTAINLY do not give a mixer “all that will be in the grooves.” These speakers are ‘real-world reference speakers.’ Unlike big, expensive ‘Studio Monitors,’ Auratones/Avantones have no low end and no high end. They sound, instead, like the majority of actual speakers that normal people will actually hear your work on. This is crucial to mixing. In the audio-post-production (IE,. sound work for video mediums) world we call these ‘TV speakers.” As-in, ‘hey charlie, lemme hear it on the TV speakers.’ As-in, Auratones/Avantones sound pretty similar to the speakers that are built in to a decent TV set. But: even better: they can handle very high power. If you need to, you can put pretty heavy watts into these guys (well, at least the Avantones) and you will not damage them.

I love editing audio on the Avantones. They just sound good at low volume levels. Audio playback on really expensive speakers at low level always puts me off. If I have to spend 3 hours editing drums, i would much rather do it at a quiet level on these little guys. BTW – in my experience – artists generally hate these things. The artist will always prefer hearing playback loud, and on the expensive speakers. Be prepared.

I applaud Avantone for being straight-forward and celebrating their product as being ‘bass-impaired’ and ‘real-world.’ I think that if you had believed this 1981 ad and purchased a pair of Auratones as your main mixing speakers, you would have been very disappointed. As a 2nd or 3rd pair of studio speakers, tho, they are great.

Pretty incredible that tape stock once made such an enormous difference in the quality of your recordings. It is a similar concept as data compression today. But while bytes are basically free, i.e., we all seem to have more data-storage capacity than we need, regardless of the bit rates and sampling frequency that we chose, tape was expensive! I remember once purchasing a blank cassette tape for almost $60. The shell was made from a ceramic composite. What mix-tape could have possibly justified this expense? I think I was like 12 years old btw.

Pretty incredible that tape stock once made such an enormous difference in the quality of your recordings. It is a similar concept as data compression today. But while bytes are basically free, i.e., we all seem to have more data-storage capacity than we need, regardless of the bit rates and sampling frequency that we chose, tape was expensive! I remember once purchasing a blank cassette tape for almost $60. The shell was made from a ceramic composite. What mix-tape could have possibly justified this expense? I think I was like 12 years old btw.

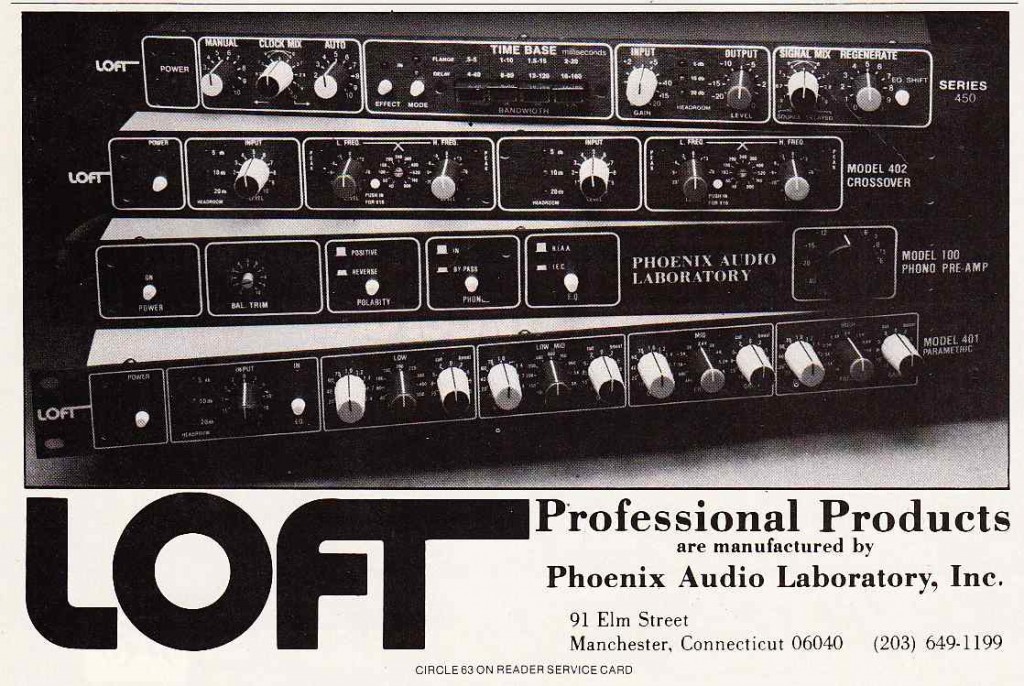

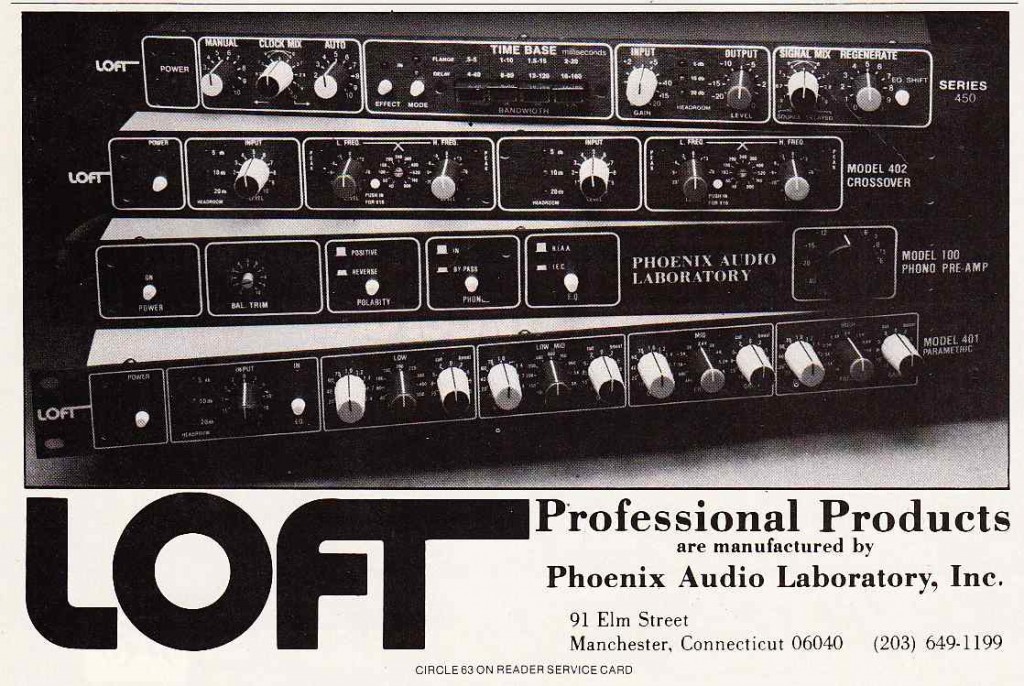

Nice. Another piece of CT pro-audio history. I recently came upon a large folio of original documentation on the entire ‘Loft’ line. There is very little information on the web about this short-lived manufacturer, other than the later employment of its founder Peter J. Nimirowski. Looks like this man ran fast+far from the pro audio world. If I can ever scare up a piece of this hardware I plan to write a feature on them.

Nice. Another piece of CT pro-audio history. I recently came upon a large folio of original documentation on the entire ‘Loft’ line. There is very little information on the web about this short-lived manufacturer, other than the later employment of its founder Peter J. Nimirowski. Looks like this man ran fast+far from the pro audio world. If I can ever scare up a piece of this hardware I plan to write a feature on them.

Update: Peter got in touch with PS.com after we published this article. Peter tells us that he stayed involved with LOFT for several years after the firm was sold. Peter also turned us on to the existence of LOFT consoles. We have no information regarding these consoles in the archive, so if anyone out there can share any images/data ETC., please do.

Ah. The classic. These Technics decks just look so great, and they sound great too. I had 3 or 4 of these at one time, literally pulled from the dumpster of an Ad Agency that ran out of storage space. Someday another will turn up. I don’t believe that these decks had balanced I/O, which would put them well in the camp of consumer audio gear, but if I remember right the sound quality was on par with any Tascam or Otari 50/50 that I ever owned.

Ah. The classic. These Technics decks just look so great, and they sound great too. I had 3 or 4 of these at one time, literally pulled from the dumpster of an Ad Agency that ran out of storage space. Someday another will turn up. I don’t believe that these decks had balanced I/O, which would put them well in the camp of consumer audio gear, but if I remember right the sound quality was on par with any Tascam or Otari 50/50 that I ever owned.

********************

***********

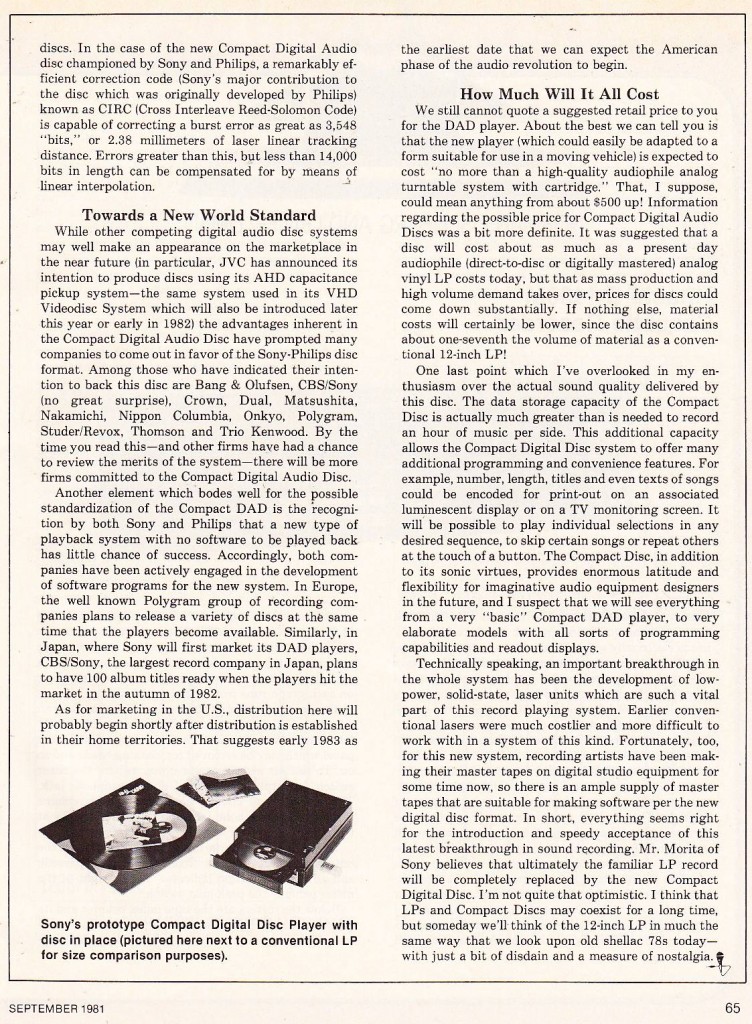

The biggest development of the year in audio, however, was no fleeting piece of hardware: it was a new audio-product-delivery technology that would forever change the world of music and audio. The Compact Digital Audio Disc. The CD.

There has been a lot of discussion about the recent decline of the Recording-Industry. A lot of accusations of poor moral decision-making on the part of music (non) purchasers; a lot of charges of greed and short-sightedness on the part of the industry; a lot of chatter that this was all ‘inevitable’ due to ‘information sharing’ in the ‘internet age.’

Can we consider, though, that perhaps it was not illegal file-sharing that began the collapse of the economic basis of the Recording Industry. Perhaps instead we can trace the problem to the decision to encode consumer audio as data. To forever free audio from issues of mechanical reproduction and the consequent loss of fidelity that occurs every time a mechanical copy (be it magnetic tape or embossed disc) is made. Once the Recording Industry made the decision to offer these digital copies (I.E., CDs) of their content for sale, they essentially surrendered the one piece of control that they possessed up to that point: The ability to manufacture clones of their products which were identical in quality to the original. By making and marketing CDs of their recordings, Record Companies essentially gave away the privileged access that they once had sole control over.

Sure, there were bootleg LPs and Tapes sold before 1981. But they did not, COULD NOT, sound as good as a Label copy. A bootleg CD sounds exactly the same as a Label CD. It has to. And a downloaded WAV file ripped from a CD sounds exactly the same as a label CD. It has to.

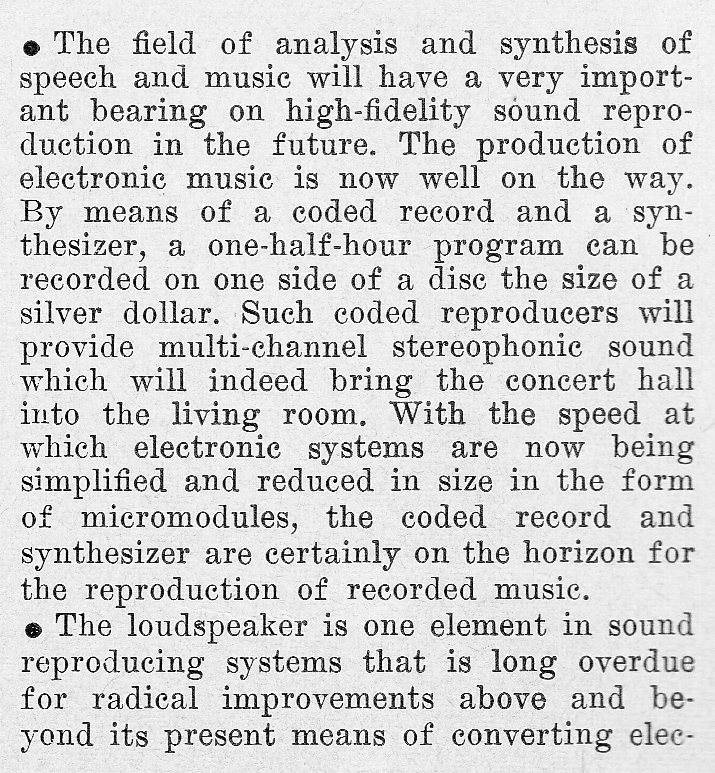

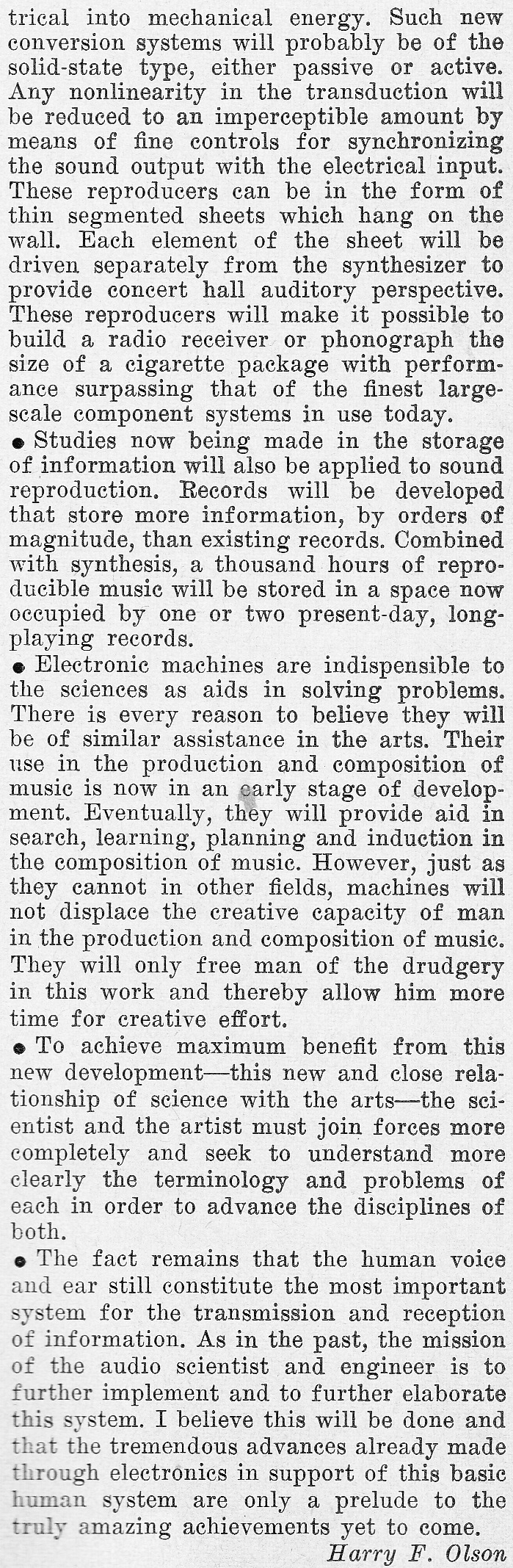

In May of 1962 “AUDIO” magazine celebrated its 15th anniversary. IIRC, AUDIO was the more consumer-facing half of what had initially been AUDIO ENGINEERING magazine; the AES Journal being created sometime in the 50s to carry the more professional articles. Anyhow, for their 15th, AUDIO asked some of the experts of the time to weigh in on THE FUTURE OF AUDIO. Harry Olson, certainly one of the greatest inventors of sound equipment who ever lived, had some comments that struck me as being incredibly prescient. I’ve never seen this reproduced anywhere, so check it out, enjoy it, share it, and take a minute to speculate on where this is all going.

In May of 1962 “AUDIO” magazine celebrated its 15th anniversary. IIRC, AUDIO was the more consumer-facing half of what had initially been AUDIO ENGINEERING magazine; the AES Journal being created sometime in the 50s to carry the more professional articles. Anyhow, for their 15th, AUDIO asked some of the experts of the time to weigh in on THE FUTURE OF AUDIO. Harry Olson, certainly one of the greatest inventors of sound equipment who ever lived, had some comments that struck me as being incredibly prescient. I’ve never seen this reproduced anywhere, so check it out, enjoy it, share it, and take a minute to speculate on where this is all going.