C. Robert Fine and Wilma Cozart Fine c.1961 (Source: T. Fine)

C. Robert Fine and Wilma Cozart Fine c.1961 (Source: T. Fine)

Today at Preservation Sound dot com we are pleased to present a special guest: T. Fine, son of high-fidelity recording pioneers C.R Fine and W.C. Fine. The elder Fines were active studio owners/engineers in the early days of stereophonic LP recording and their efforts brought the world one of the most successful series of LPs ever manufactured: Mercury Records’ Living Presence series (click here for a contemporary reissue of much of this material).

The younger Mr. Fine presents a history of Fine Recording, INC., the studios, and the equipment that was used; he has also generously provided PS Dot Com with some previously unavailable images of the operation. We’ll begin with a five-page article from Popular Science (1967) which documents a recording session at Fine Recording, INC.

Click here to read the original article at Popular Science Dot Com

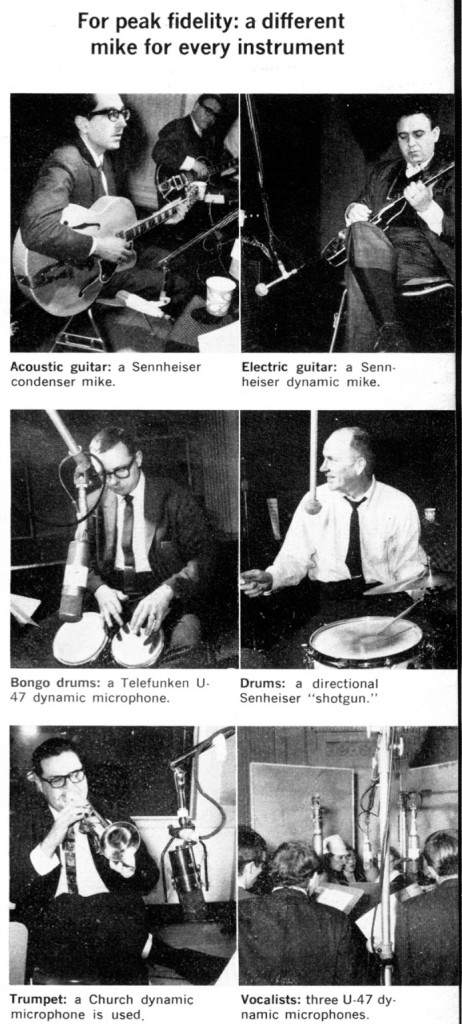

(image source: Popular Science, August 1967)

T. Fine: ” Fine Recording Inc. (h.f. FRI) was a production complex that eventually encompassed four studios, extensive disk-mastering operations, and Walter Sear’s Moog laboratory. FRI was located in the Great Northern Hotel on 57th Street in Manhattan.

The Great Northern Hotel, Home of FRI., as it appeared in the 1950s (SOURCE: T. Fine)

The Great Northern Hotel, Home of FRI., as it appeared in the 1950s (SOURCE: T. Fine)

“The building was torn down in the late 1970’s and the Parker Meridian Hotel is on the site now.

Pouring of the foundation of the Parker Meridian taken from the 7th floor of Sterling Mastering circa 1977 (photo: Bob Ludwig)

Pouring of the foundation of the Parker Meridian taken from the 7th floor of Sterling Mastering circa 1977 (photo: Bob Ludwig)

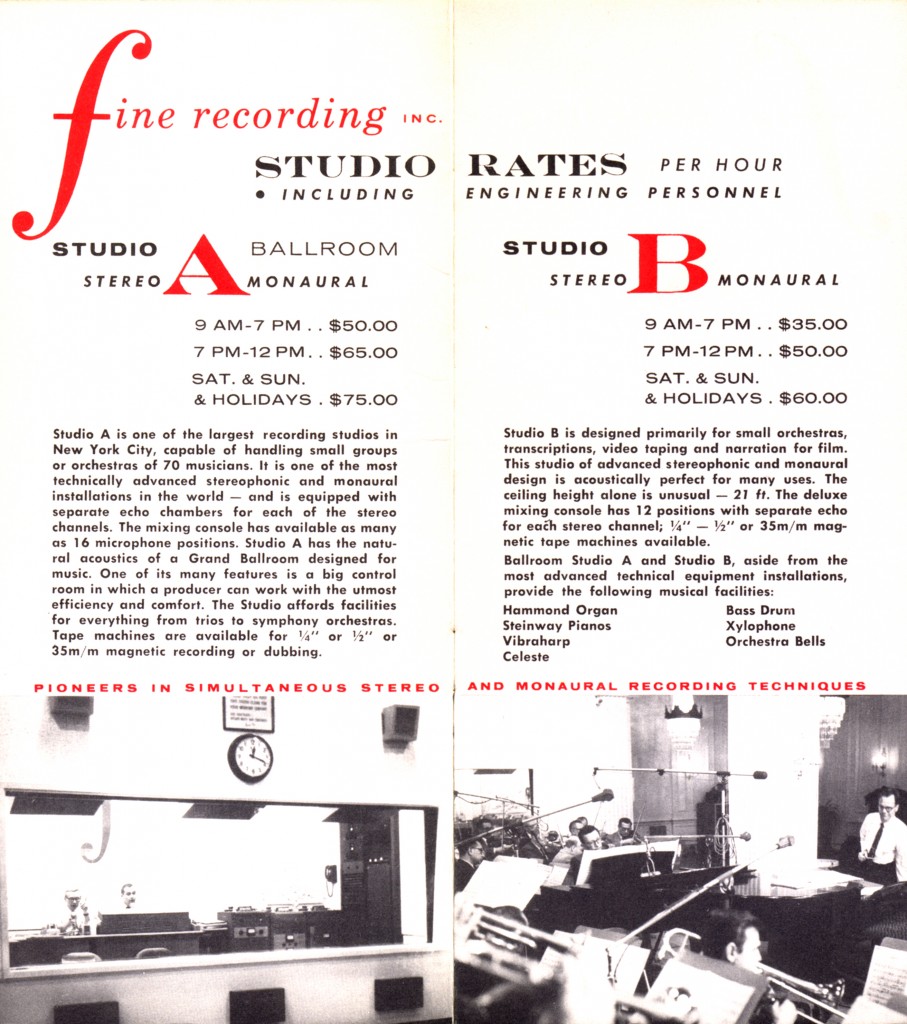

“Fine Recording began operation in 1957, first doing mixing and disk mastering while the hotel’s former Ballroom was transformed into a recording space.

Above: The ballroom of the Great Northern Hotel c. 1900, later to become Fine Recording Studio A. The Tiffany glass ceiling remained throughout. (SOURCE: T. Fine)

Above: The ballroom of the Great Northern Hotel c. 1900, later to become Fine Recording Studio A. The Tiffany glass ceiling remained throughout. (SOURCE: T. Fine)

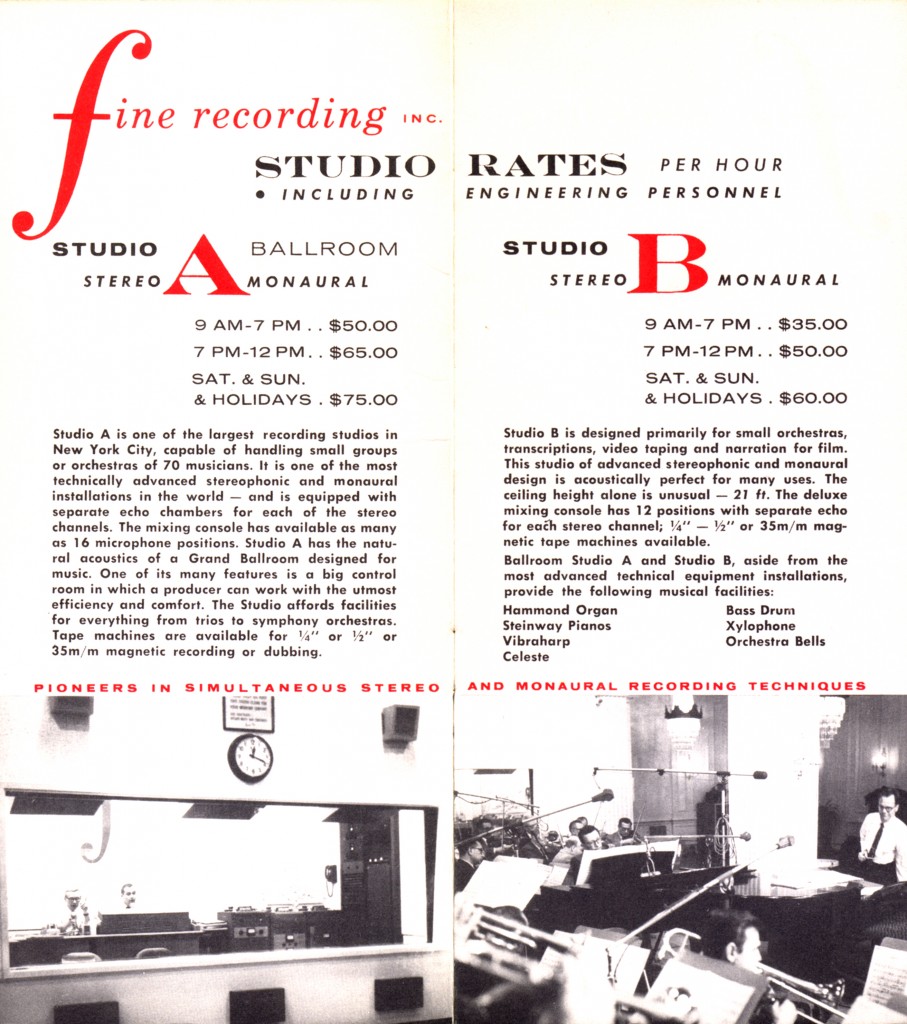

“In the summer of 1958, the first recording sessions took place in Ballroom Studio A, and continued almost daily until 1971. Studio B, which was located in what had been the ballroom’s service kitchen, was used for small-group sessions, voice-over recording, transcription services and other purposes not requiring a large recording room.

Fine Recording, INC rate-card c. 1959. In today’s currency: multiply by 11. (SOURCE: T. Fine)

Fine Recording, INC rate-card c. 1959. In today’s currency: multiply by 11. (SOURCE: T. Fine)

“A growing sound-for-film business required a film-specialized space, and Studio C was built in 1959, in the suite of rooms on the top floor where conductor Dimitri Mitropoulos had lived. A few years later, the adjoining suite became available, and Studio D was built as a second sound-for-picture studio. Studio C and D shared a film-machine room and both were equipped for 35mm and 16mm synchronized picture and sound work. The disk-mastering suite, also on the penthouse level, had stereo and mono mastering rooms.

In the late 60’s, Walter Sear had a studio/Moog synthesizer production lab on the 12th floor. Sear was Walter Moog’s NYC regional representative and he provided Moog effects exclusively to Fine Recording clients. After the success of Walter (later Wendy) Carlos’s Moog album, “Switched On Bach” (Columbia), other artists quickly jumped on the Moog bandwagon. Among them were Dick Hyman and Richard Hayman, who recorded several Moog-centric albums for Command. (Ed. note: click here for an excellent Moog cut from Hyman). Walter Sear did the Moog programming and some of the engineering on those albums, and also recorded his own Moog album for Command, “The Copper Plated Integrated Circuit.”

From the early 1960’s until the end of operations, there was a large tape-duplicating operation in the basement. Duplicating was originally set up for quarter-track, full-track and 2-track reels, but Fine Recording was also one of the first east coast facilities to duplicate 4-track “Muntz” cartridges, 8-track Lear cartridges and the Philips Compact Cassette.

The studio ceased operation and was sold to Reeves Cinetel in 1971.

************

*******

***

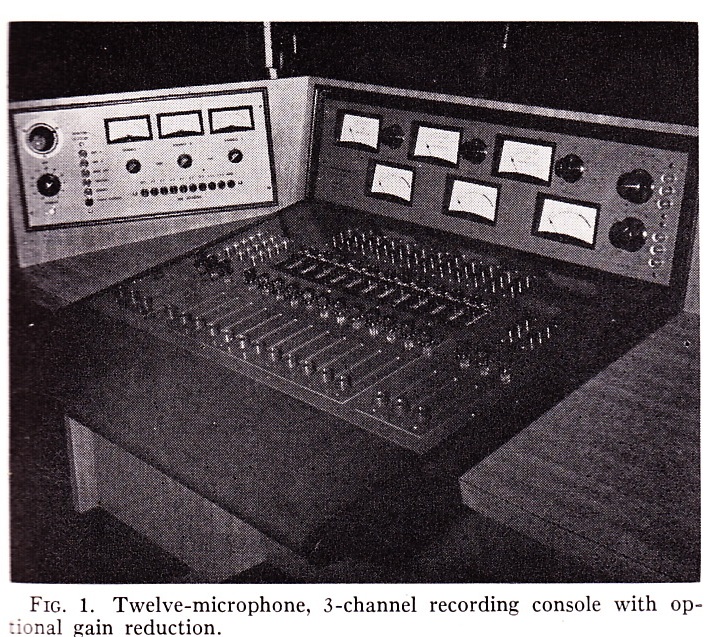

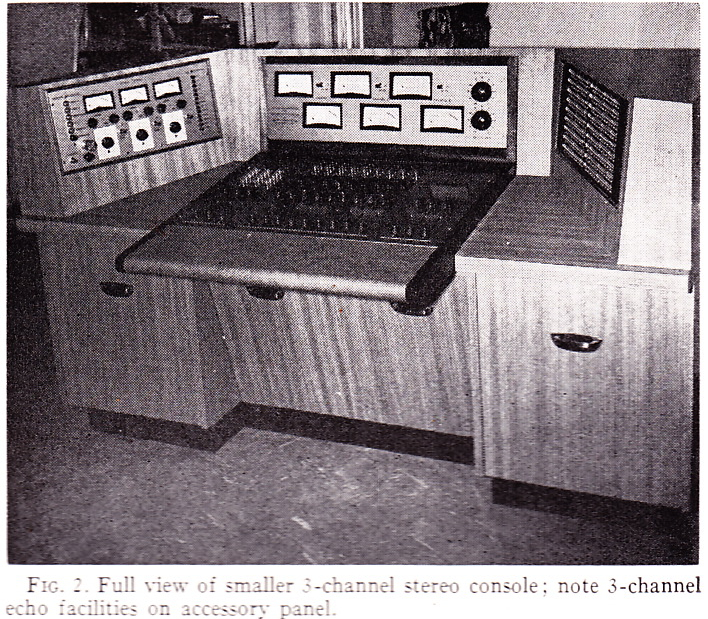

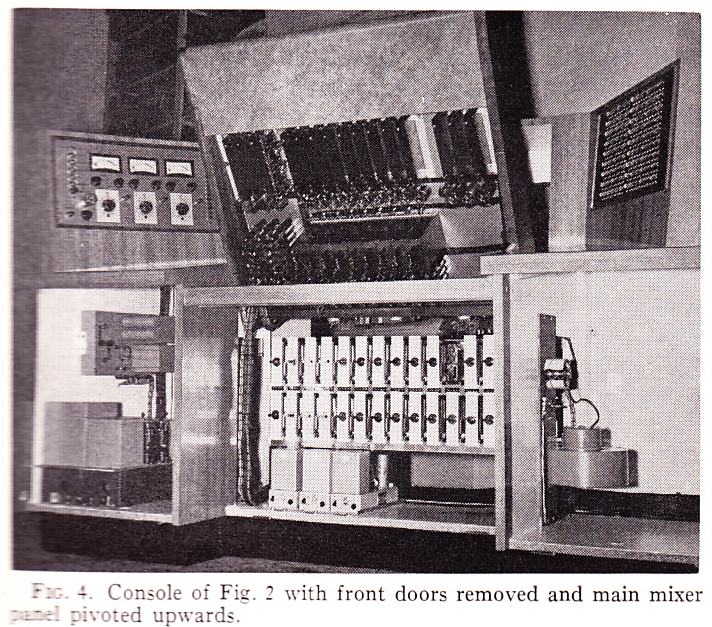

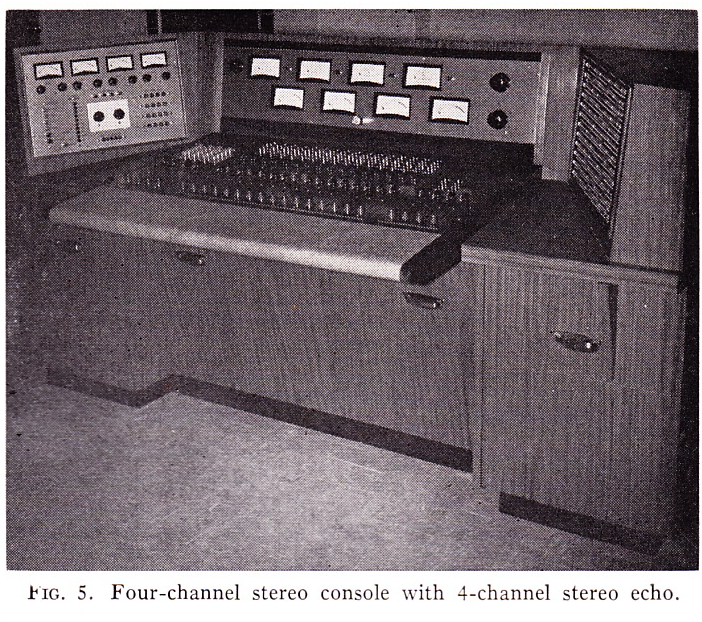

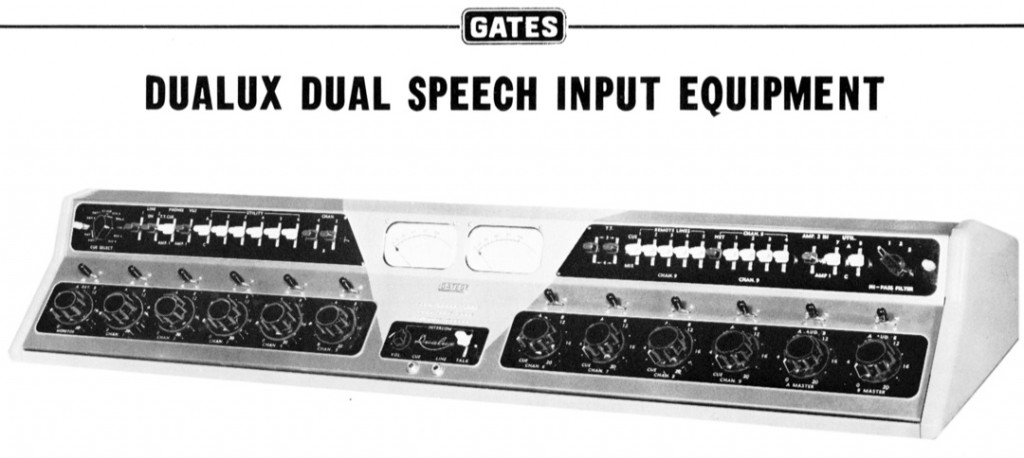

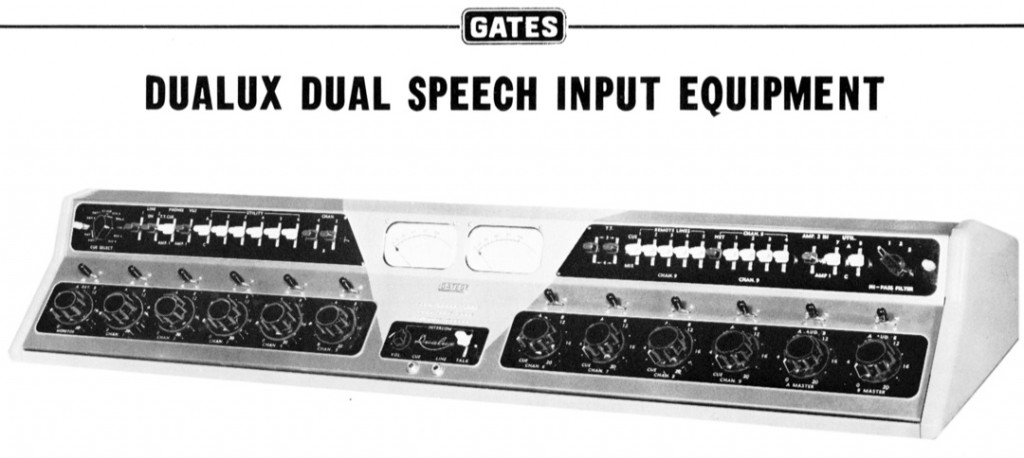

As for equipment: Studio A started out with a Gates Dualux mixing console, which was modified heavily over the years. By 1960, a center-channel buss had been built, and facilities for echo send and return were present from the get-go. The version pictured in the PopSci article (see above – ed.) shows the full extent of the modifications.

Above: the 1960 Gates Dualux console, a slighter later version than installed at FRI. The Dualux at FRI used 5879 tubes in the mic preamps rather than EF86. Click here to DL schematics for the Gates 5879 preamps: Gates-M5215_preamp. Click here to download data on the Gates Dualux: Gates_Dualux_1960

Above: the 1960 Gates Dualux console, a slighter later version than installed at FRI. The Dualux at FRI used 5879 tubes in the mic preamps rather than EF86. Click here to DL schematics for the Gates 5879 preamps: Gates-M5215_preamp. Click here to download data on the Gates Dualux: Gates_Dualux_1960

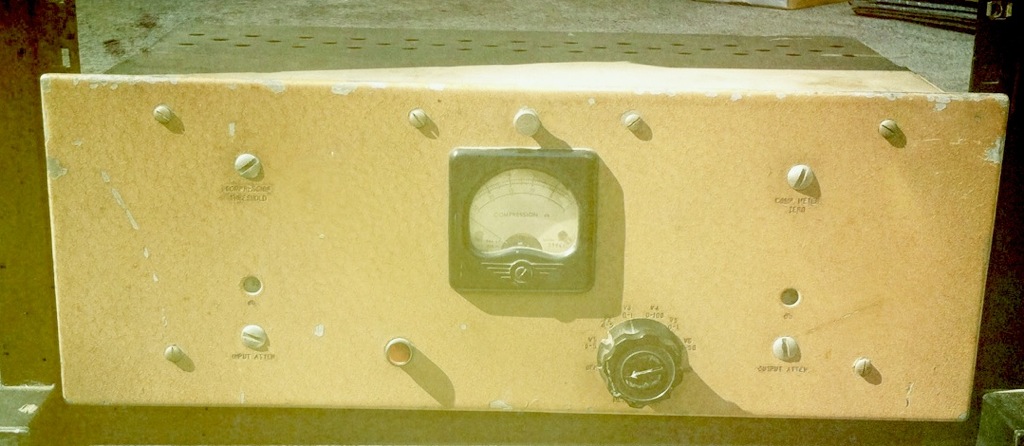

“Fine Recording did not use the Gates Console’s line amps. Instead the console outputs went through Altec 322C Limiter Amplifiers, which were set to a fixed gain (click here to DL the Altec 322C schematic: Altec-322C)). If you wanted a clean, linear signal (IE., no compression), you just used the console channels conservatively. If you drove the channels beyond a certain level, you’d hit the threshold of the limiter/compressor. This is how the “Command Sound” was achieved, characterized by bright up-front horns and crunched drum set, but retaining dynamics and punch in the percussion. (ed. note: ‘Command’ was a prominent record label in the 1960s. For an example of the typical Command sound, click here)

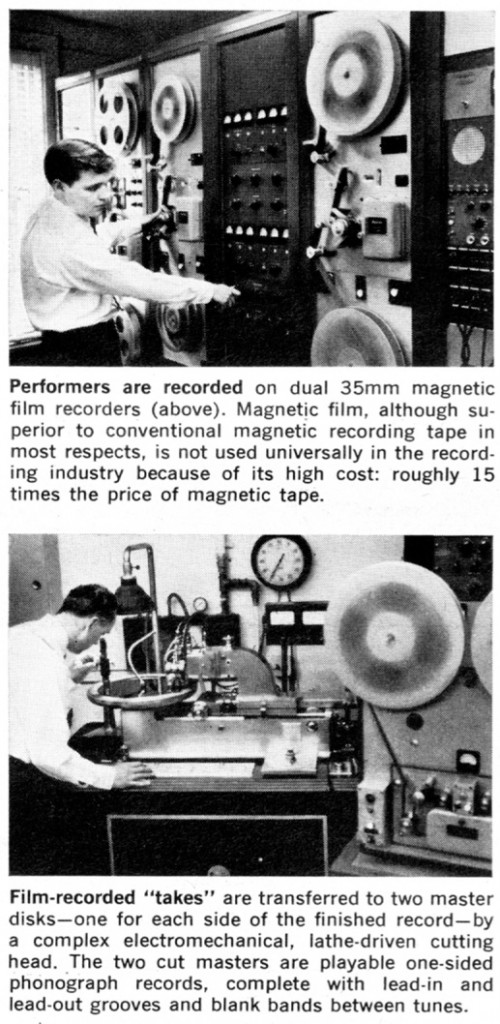

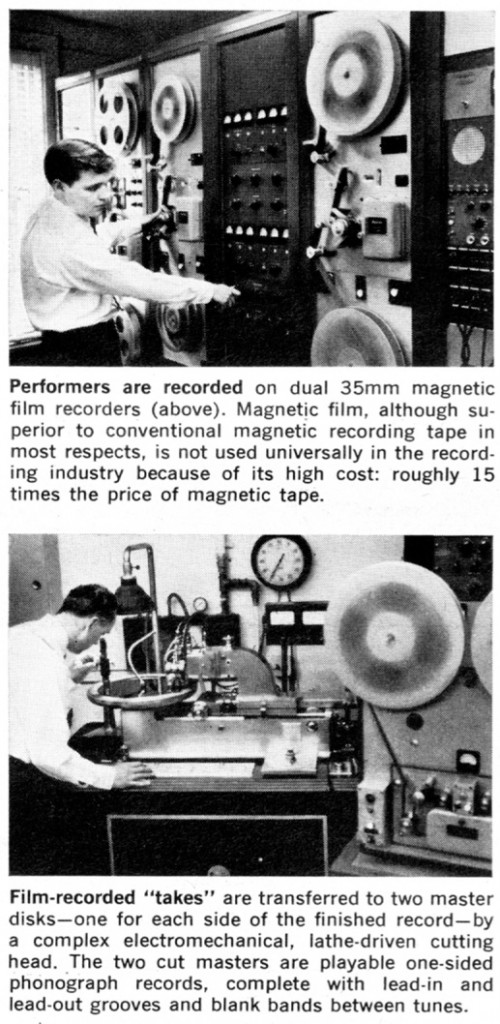

Regarding the session depicted in the Popular Science article: it is of special interest because the master medium was 35mm magnetic film, not tape. The article covers the process from session to mastering to pressing plant. The record in question was one of Enoch Light’s early releases on his Project 3 label (Light started that label after he left Command Records in 1966).

(image source: Popular Science 8/67)

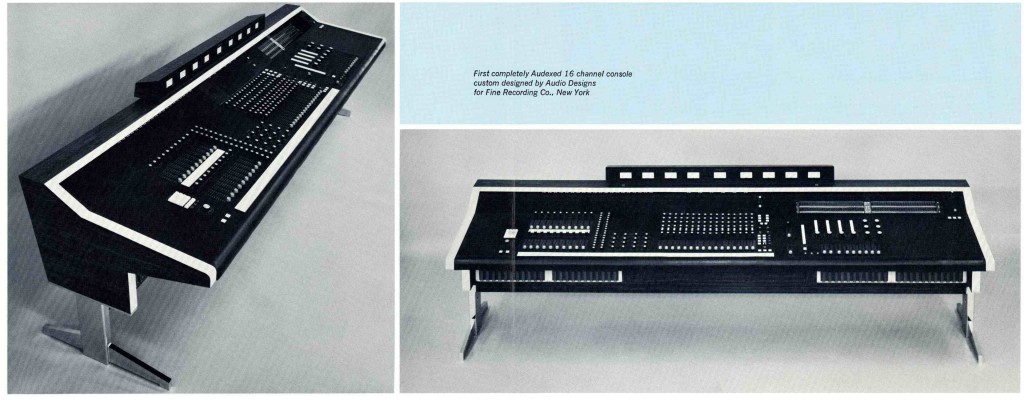

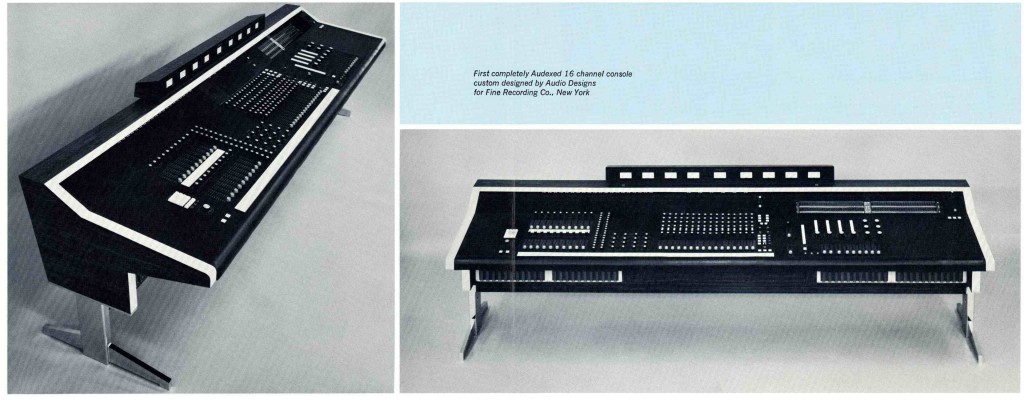

“In 1969, Studio A was rebuilt. The new Audio Designs & Manufacturing (ADM) console installed was, at the time, among the largest desks outside of Hollywood.

Above: The Fine ADM Console. (SOURCE: T. Fine)

“It featured early assign-automation featuring a patented system. Studio A was originally mono and 2-track. It later evolved to mono and 3-track, and the 1969 build was for 16-track recording and also 6-track monitoring and mixing for films.

Studio B started out with an RCA console from the former Fine Sound studio on 5th Avenue. This desk had been rebuilt for 3-channel in the mid-50’s (it was based on 3 separate mixers of 4 inputs each, with 3 echo sends and returns). In 1967, Studio B was rebuilt for 8-track, with a new ADM mixing desk. In those days, engineers like to monitor all the tape tracks, but using 8 Altec 604 monitors was not practical. Fine Recording contacted JBL and the famous JBL model #4310 three-way monitor (which was also sold by the thousands as a home-stereo speaker, the Century L-100) was born. (click here to download further information regarding the JBL/ FRI connection). Studio B later evolved to a 12-track (a short-lived 1? tape format made by Scully), and then 16-track.

Studio C, the first film-mixing room, had a 1940’s vintage Western Electric/MGM all-passive console, also originally installed at Fine Sound on 5th Avenue. The console took line-level from the machine room and its output was down to about mic level, so Altec amplifier/compressors were used to get back the gain and control peak modulation. Hundreds of films, TV commercials, and special productions were mixed on this console over the years. It later lived at Sear Sound and is now owned by the Museum of Sound Recording group. Studio D’s console was the first all-transistor board at the studio, built in 1966 out of early ADM modules by studio chief engineer Bob Eberenz.

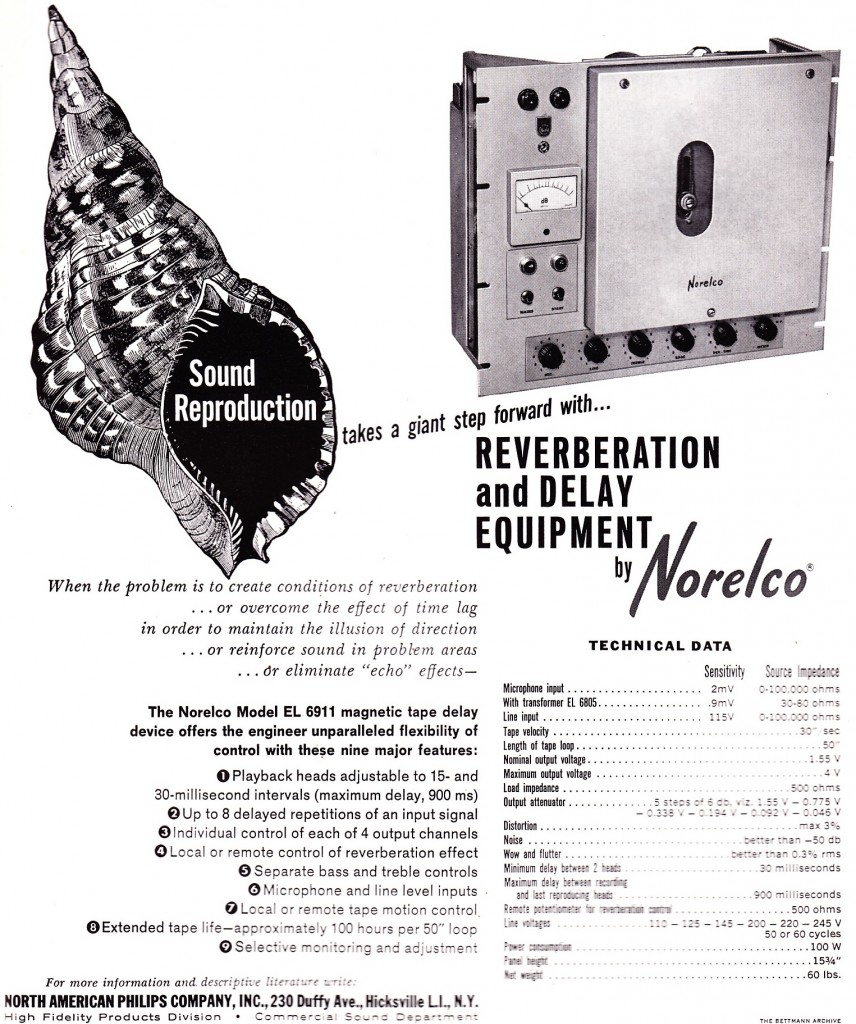

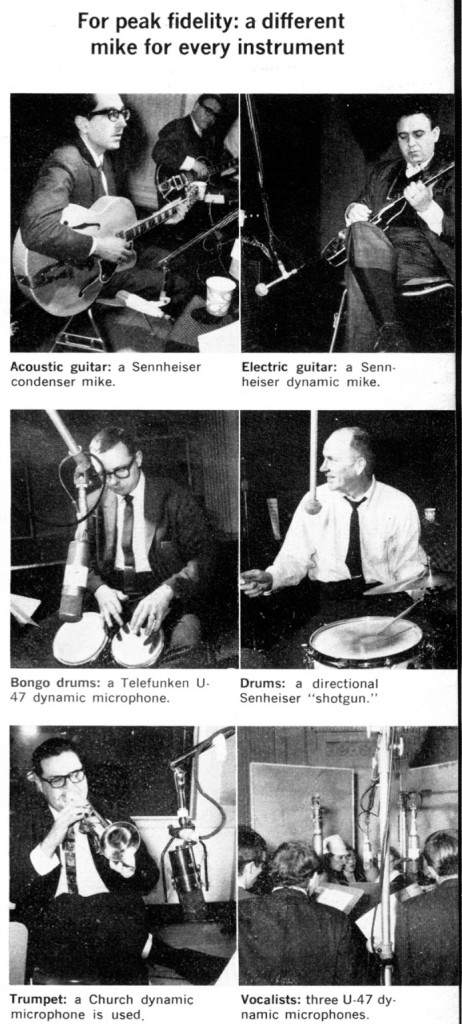

Monitoring was done on Altec A7’s powered by McIntosh amps. Studio B eventually ended up with 8 JBL 4310 speakers powered by smaller McIntosh amps. Tape machines were generally Ampex, but there were Scully 8-tracks and 12-tracks in Studio B for a while. Mics included a bunch of U-47’s, a bunch of RCA ribbon mics (mainly 44BX and 77DX), some EV 666 dynamics, Church mics acquired from Everest, Schoeps M201’s (used on the Mercury Living Presence recordings, and in the studio), and a few other types here and there. There were Pultec equalizers all over the place. Also, there were many special-purpose effects devices and modifications to “stock” pieces in order to gain various sounds and effects desired by clients.

From Popular Science 8/67: The mics of Fine Recording. Evidently there was some editorial confusion regarding microphone-type classification.

From Popular Science 8/67: The mics of Fine Recording. Evidently there was some editorial confusion regarding microphone-type classification.

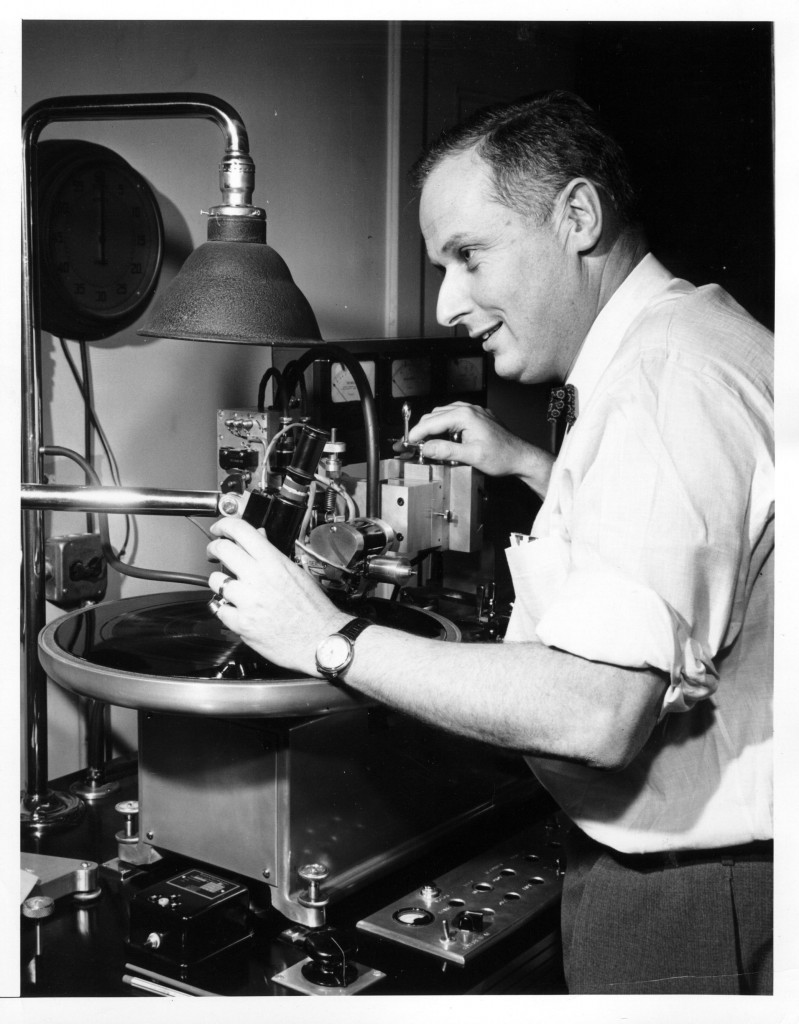

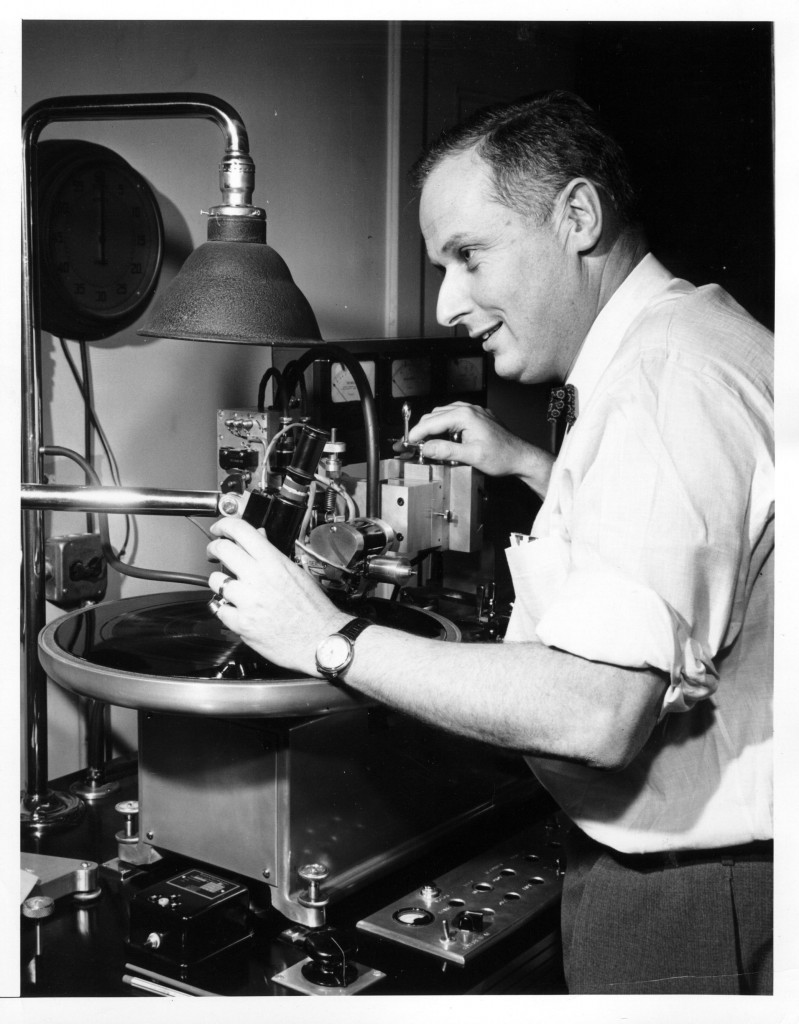

“The cutting lathes were Scully, with customized Westrex heads. Stereo cutting amps were McIntosh 200W, capable of 1kW clean peak power! Mono cutting amps were Westrex. Most of the equipment in the duplicating operation was customized or modified.

R. Fine at the Lathe, c. 1959 (SOURCE: T. Fine)

R. Fine at the Lathe, c. 1959 (SOURCE: T. Fine)

“In 1960, Fine Recording acquired the defunct Everest recording studio in Bayside Queens (see image at head of this article – ed.). This was operated as a separate studio for several years. The Everest studio had a custom Westrex console and was designed for 3-channel 35mm mag-film recording. Eventually, the Bayside location was shut down and the equipment integrated into the Manhattan facility. The old Westrex console sat in a store room and was eventually tossed; think of the value of those components today! (UPDATE: we’ve added detailed information about the Fine Bayside location at the end of this article. Click here and scroll down to read more).

The principle players at Fine Recording were owner/president C. Robert Fine, VP and head of mastering George Piros, VP and chief technical engineer Bob Eberenz. Notable recording engineers who worked at the studio over the years included Fred Christie (later of MediaSound), Russ Hamm (Sear Sound, Gotham Audio), Walter Sear (Sear Sound), John Quinn (The Mix Place), Kenny Fredrickson (The Mix Place) and Gerry Block (Sigma Sound Studios NYC). Projectionists, machine room techs and various other employees also had long careers around the NYC studio scene.

Along with owning and running the studio, Bob Fine owned a recording truck, used primarilly to make the Mercury Living Presence classical recordings. His wife, Wilma Cozart Fine, was the VP of classical music at Mercury Records until she retired in 1964 to raise their family. Bob Fine was also an inventor, receiving ten U.S. patents. After Fine Recording, Bob Fine worked for Reeves Telecine until 1974, and then worked as a consultant and studio designer. Fine designed, oversaw the building of, and initially ran the Armstrong Audio/Video complex in Melbourne Australia (later AAV Australia). He later worked at The Mix Place in NYC. Bob Fine passed in 1982. Wilma Cozart Fine returned to the music business in the 1990’s, remastering more than 100 Mercury Living Presence albums for CD release. Wilma Fine passed in 2009.”

Follow the link below for a list of some noteable albums recorded at Fine Recording INC. And for an excellent + thorough interview of Bob Fine by Bert Whyte, click here to download: Audio-681_Fine_Recording.pdf

Above: the Fairchild 661 Auto-ten (a noise gate, apparently), 740 Lathe, 602 and 600 Conax (de-essers, apparently), 670 stereo limiter, 663 Compact console channel compressor, and 666 compressor, which wants you to know that it is emphatically NOT a vari-mu compressor.

Above: the Fairchild 661 Auto-ten (a noise gate, apparently), 740 Lathe, 602 and 600 Conax (de-essers, apparently), 670 stereo limiter, 663 Compact console channel compressor, and 666 compressor, which wants you to know that it is emphatically NOT a vari-mu compressor.