In a previous article, we offered a thorough treatment of Fine Recording, INC. (hf. “FRI”), the NYC recording studio that pioneered high-fidelity music recording in the 1950s and 60s. FRI principal Bob Fine also built and maintained a high-fidelity remote recording truck beginning in 1951. This recording truck was used to create master recordings for dozens of albums for the Mercury Living Presence and Command Classics labels. Perhaps most remarkably, the truck saw thousands of hours of action not only throughout the United States, but on several European tours as well. In 1962, it was the first American recording unit to be allowed into the Soviet Union to record Russian musicians. PS dot com contributor Tom Fine, son of Bob Fine, has provided us with some rare period documentation of the truck along with many never-before-published photographs of the operation in action. Here’s the story of Bob Fine’s remote truck as told to us by Tom Fine.

In a previous article, we offered a thorough treatment of Fine Recording, INC. (hf. “FRI”), the NYC recording studio that pioneered high-fidelity music recording in the 1950s and 60s. FRI principal Bob Fine also built and maintained a high-fidelity remote recording truck beginning in 1951. This recording truck was used to create master recordings for dozens of albums for the Mercury Living Presence and Command Classics labels. Perhaps most remarkably, the truck saw thousands of hours of action not only throughout the United States, but on several European tours as well. In 1962, it was the first American recording unit to be allowed into the Soviet Union to record Russian musicians. PS dot com contributor Tom Fine, son of Bob Fine, has provided us with some rare period documentation of the truck along with many never-before-published photographs of the operation in action. Here’s the story of Bob Fine’s remote truck as told to us by Tom Fine.

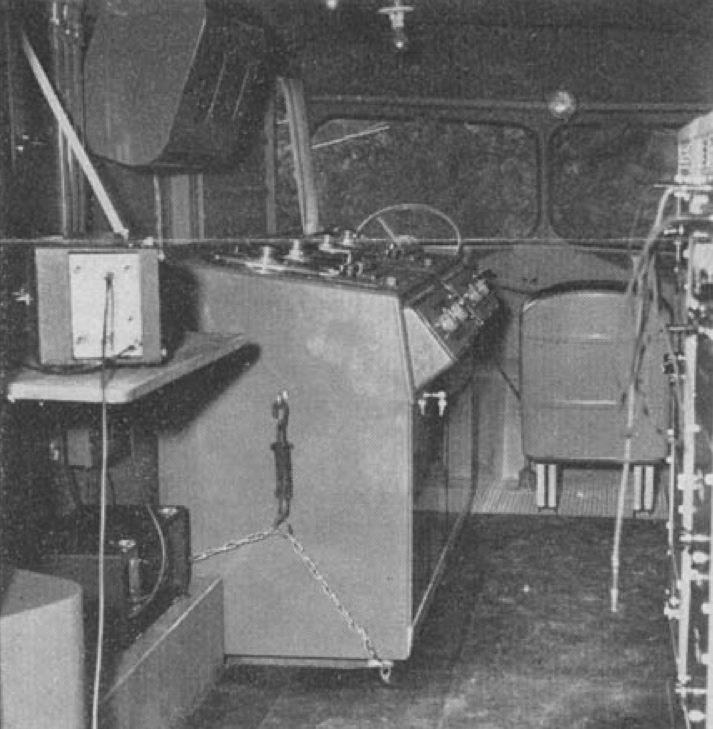

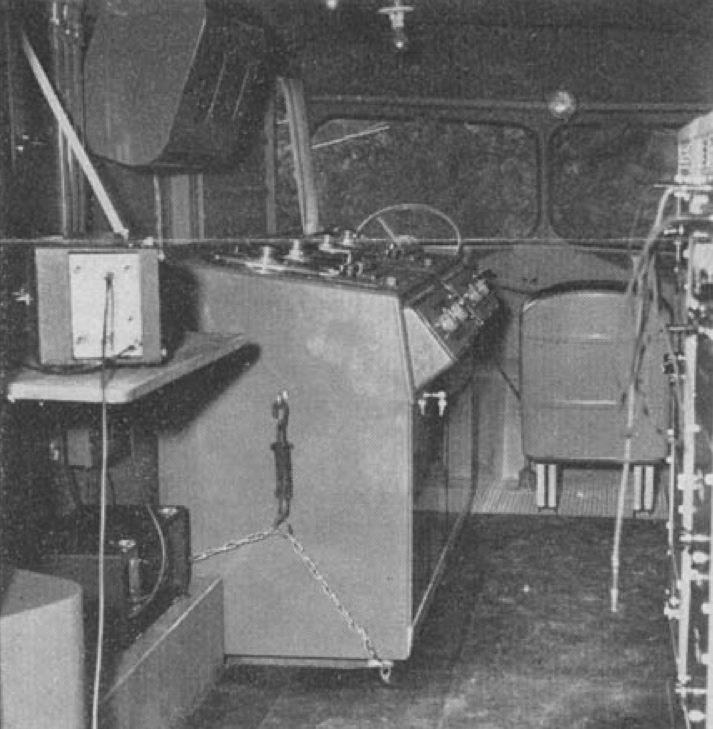

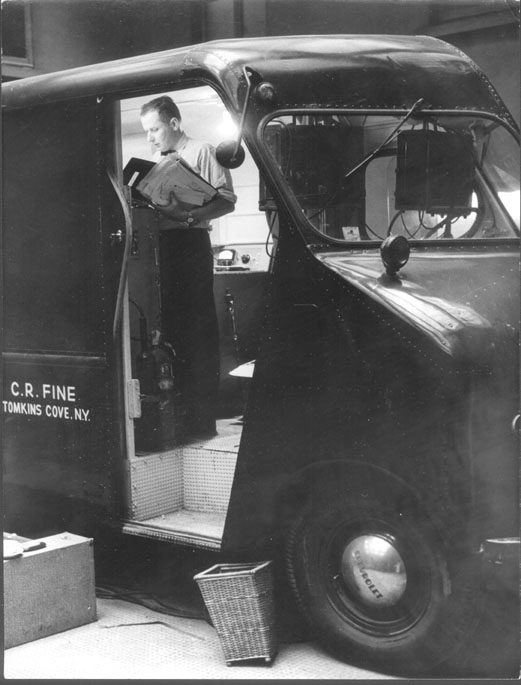

Interior of the truck (1951)

Interior of the truck (1951)

“Jerome Hill was an heir to the Great Northern Railroad founder. Hill was a documentary film maker as well as a painter and philanthropist. One of his early movies was a documentary on the painter Grandma Moses. The film’s soundtrack was recorded and mixed at Reeves Studios in NYC, where Bob Fine was the chief engineer. Hill had a house in Rockland County, near Bob Fine’s home in Tomkins Cove.”

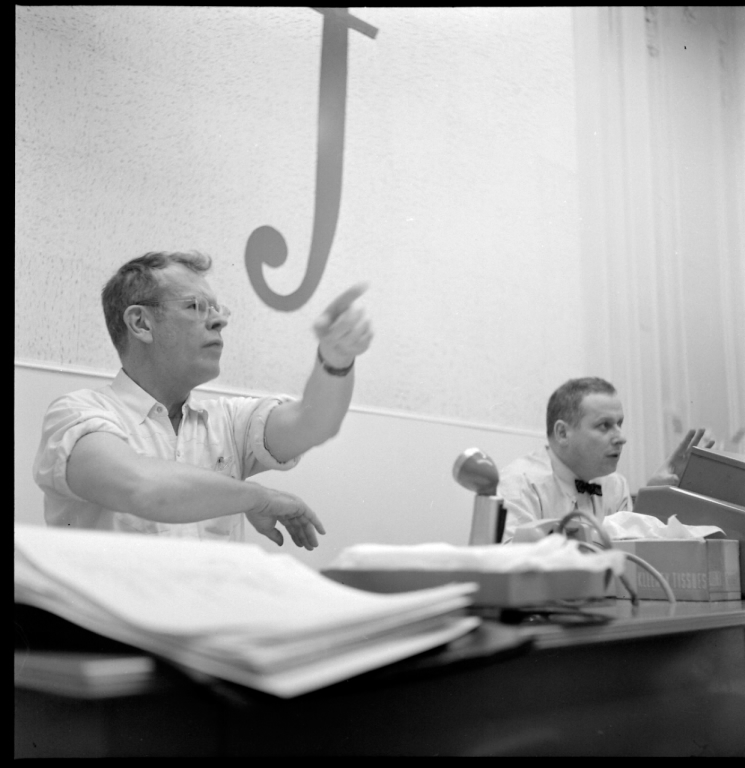

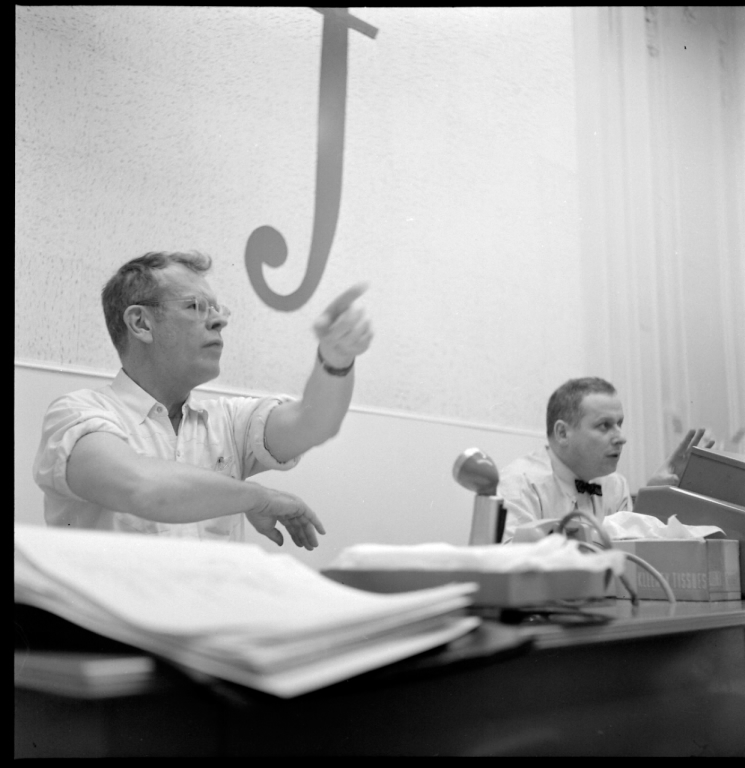

Hill (L) and Fine (R) mixing Hill’s film “The Sand Castle” at Fine Recording Studio A.

Hill (L) and Fine (R) mixing Hill’s film “The Sand Castle” at Fine Recording Studio A.

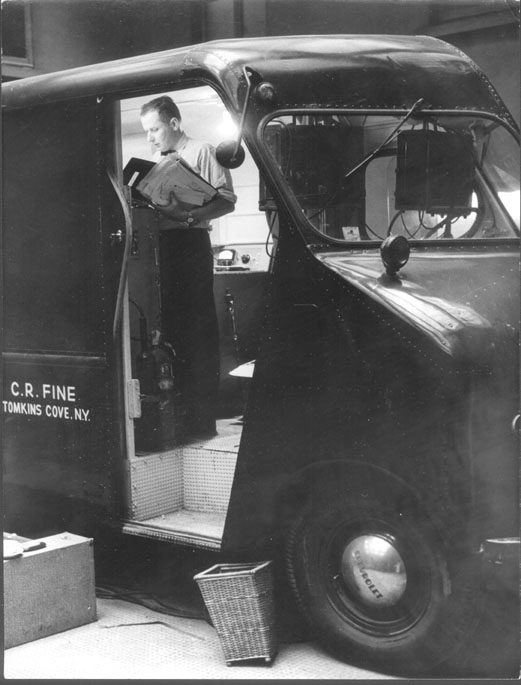

“At the time Bob Fine left Reeves to form his own company, Fine Sound, Hill was beginning work on a film about doctor, humanitarian and organist Albert Schweitzer. When Hill was planning the film in 1951, he decided he wanted a mobile film studio to go to France and spend several weeks filming Dr. Schweitzer in his home town, and also capture Dr. Schweitzer playing the organ in his home church. Hill put up the funding and Fine designed and built a custom vehicle to accomplish this. Built on a 1951 Chevrolet frame, the truck was initially dubbed the “Cinecruiser.”

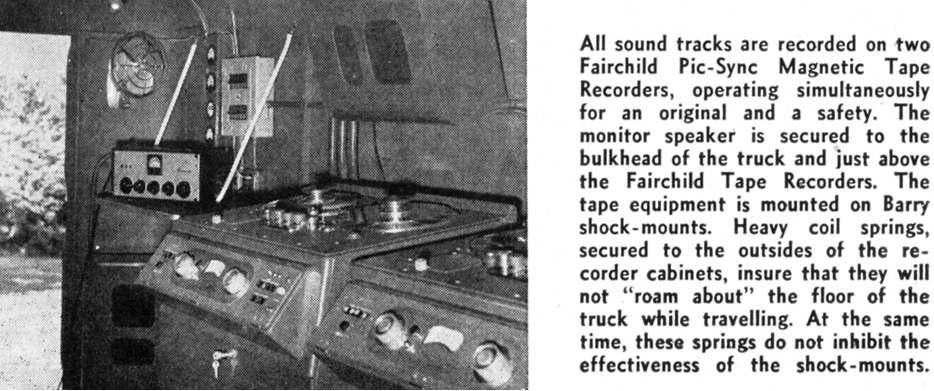

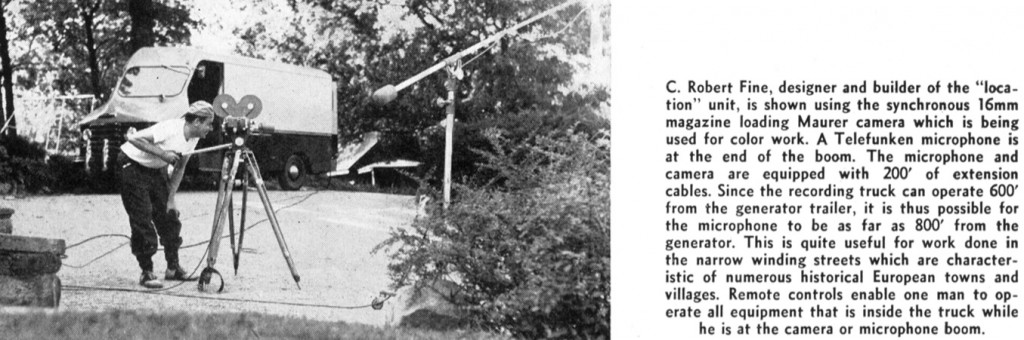

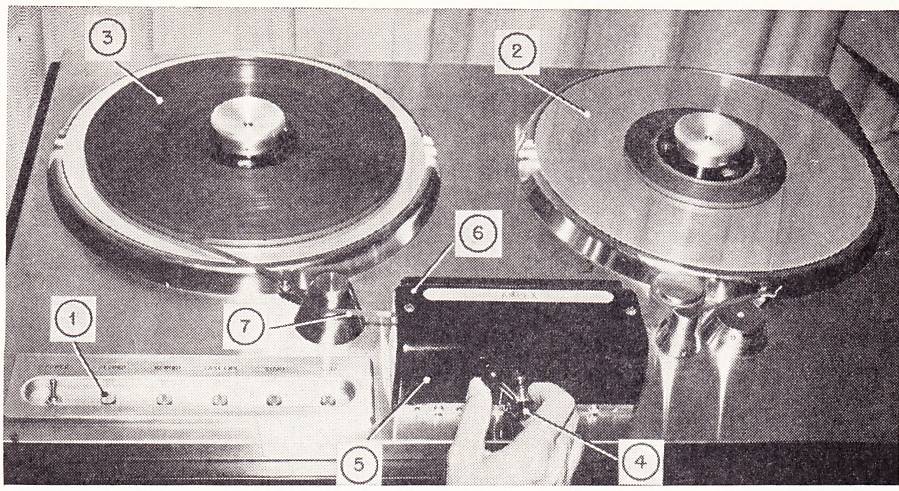

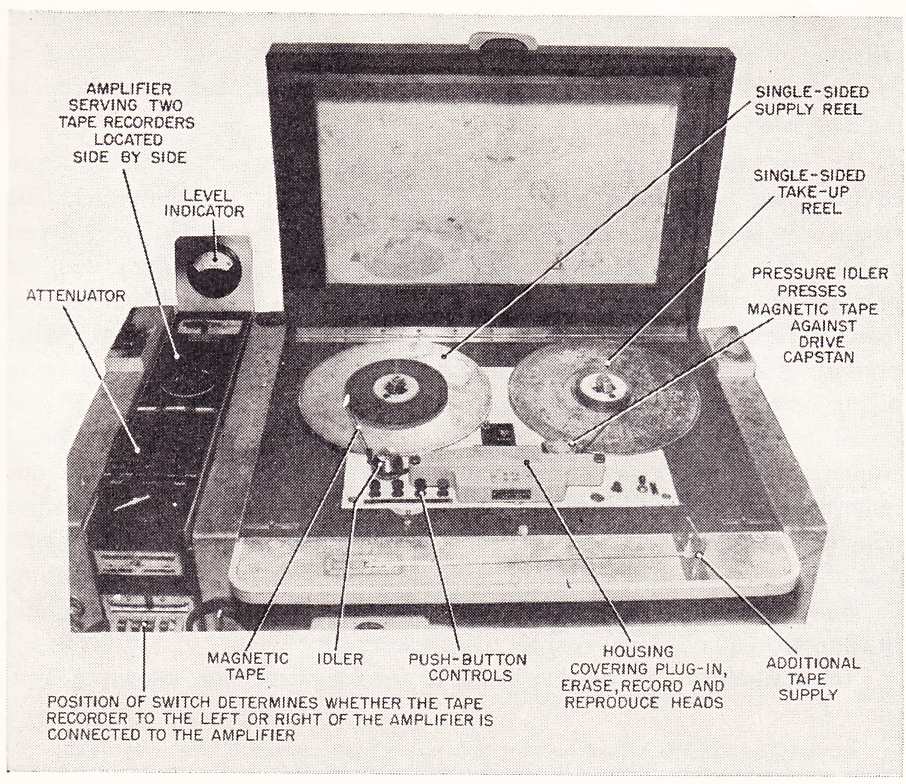

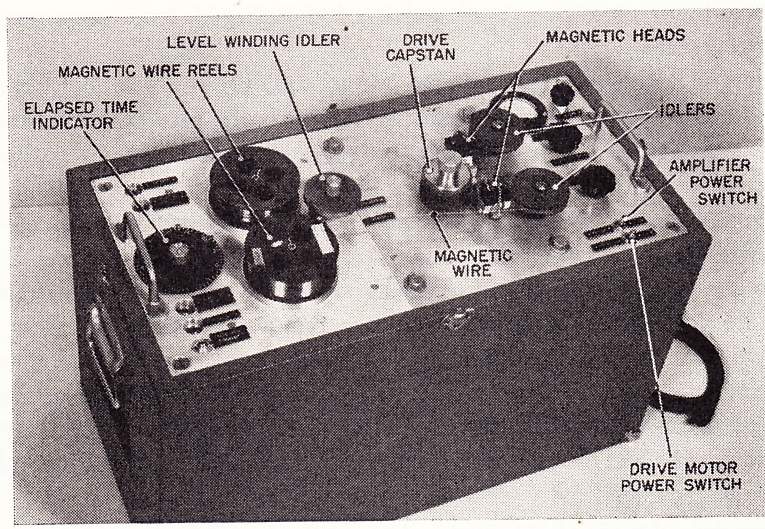

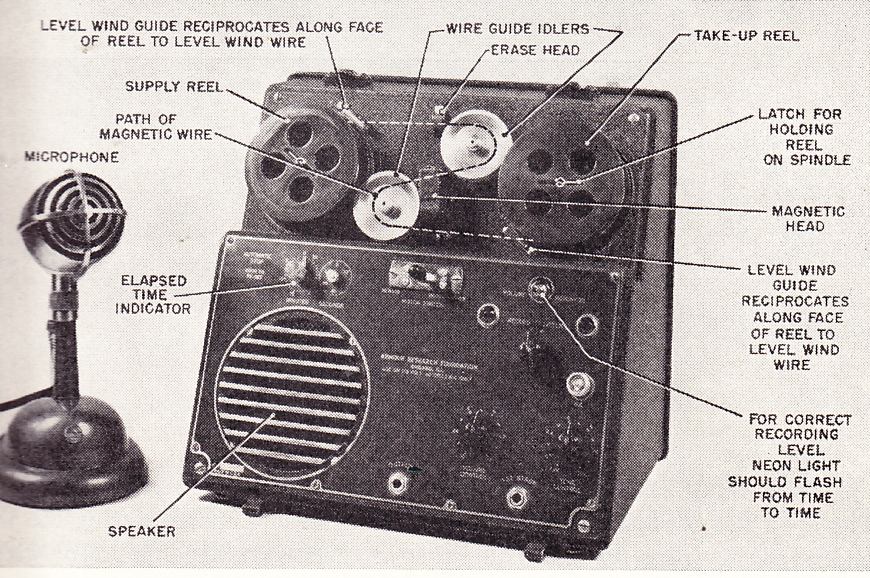

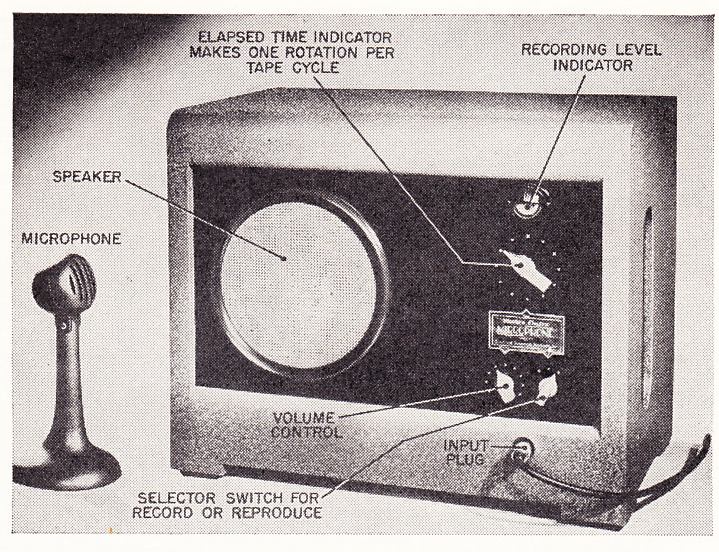

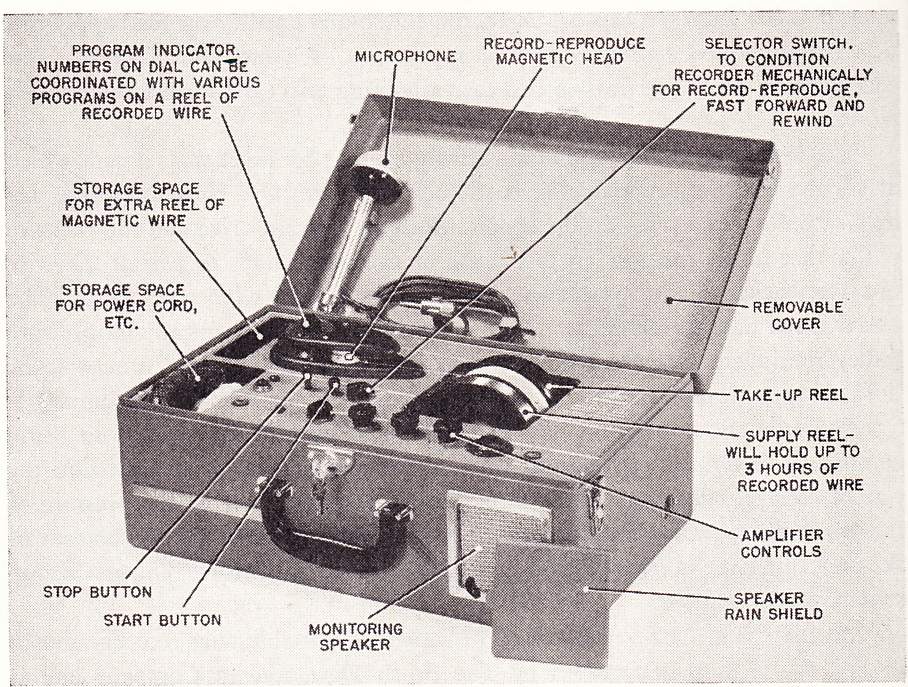

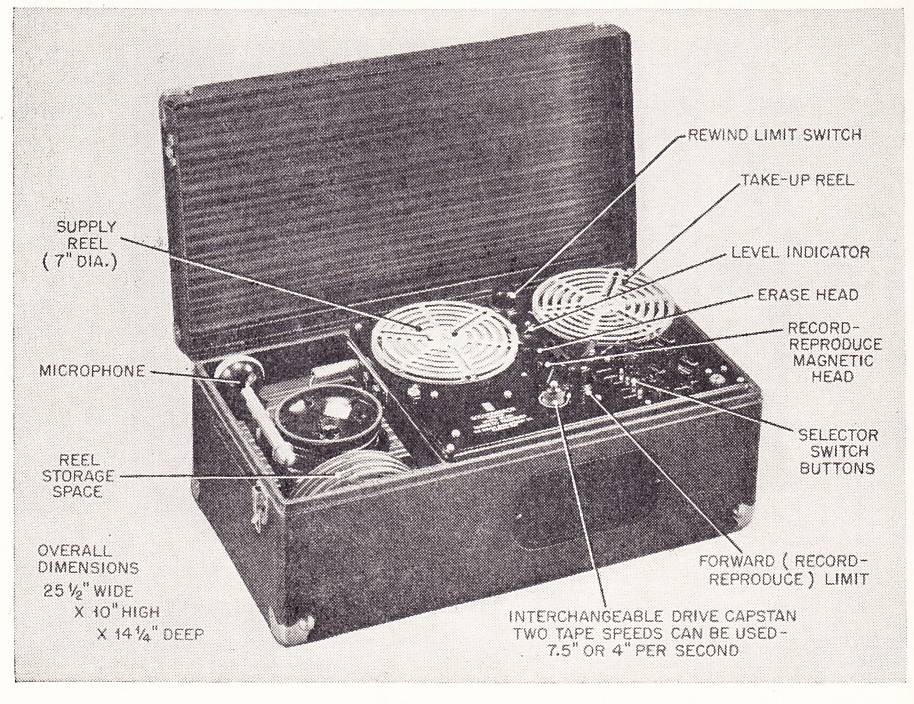

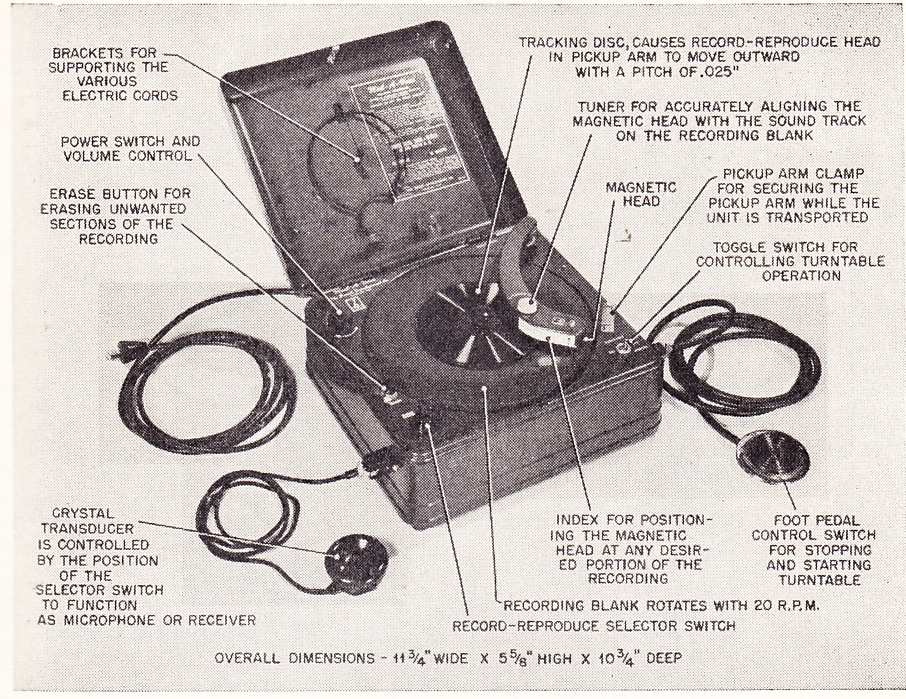

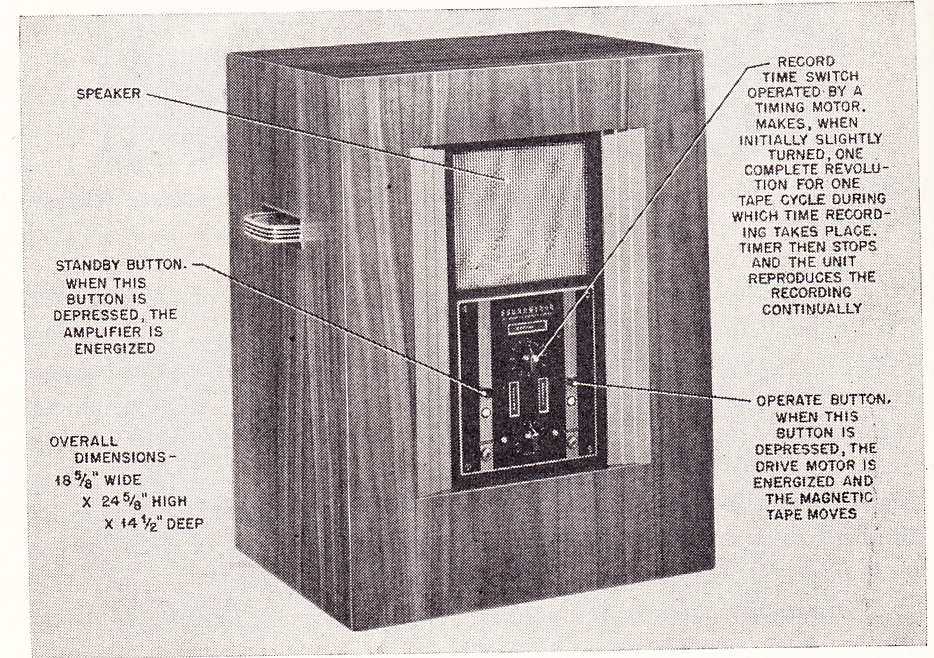

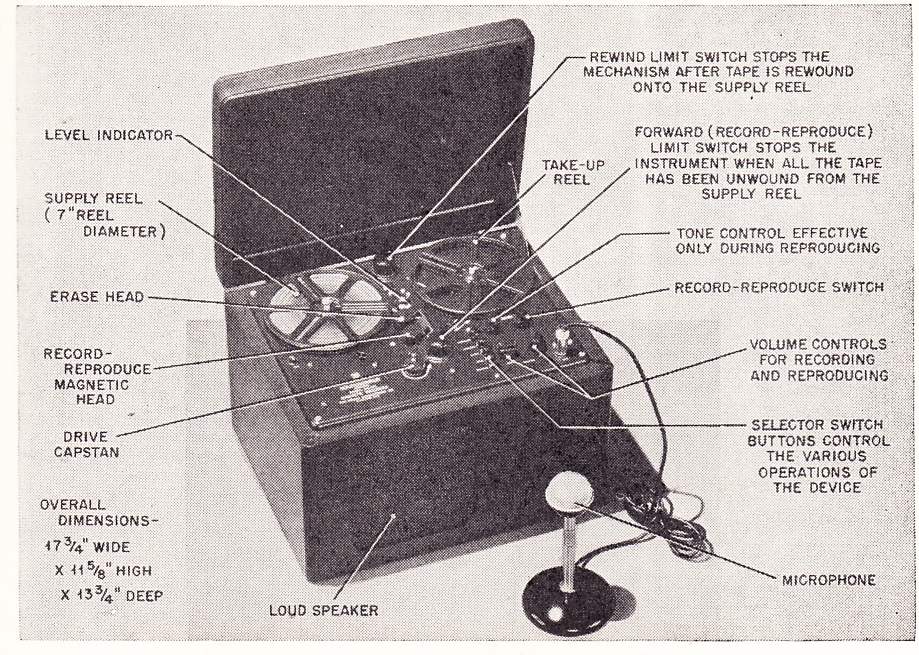

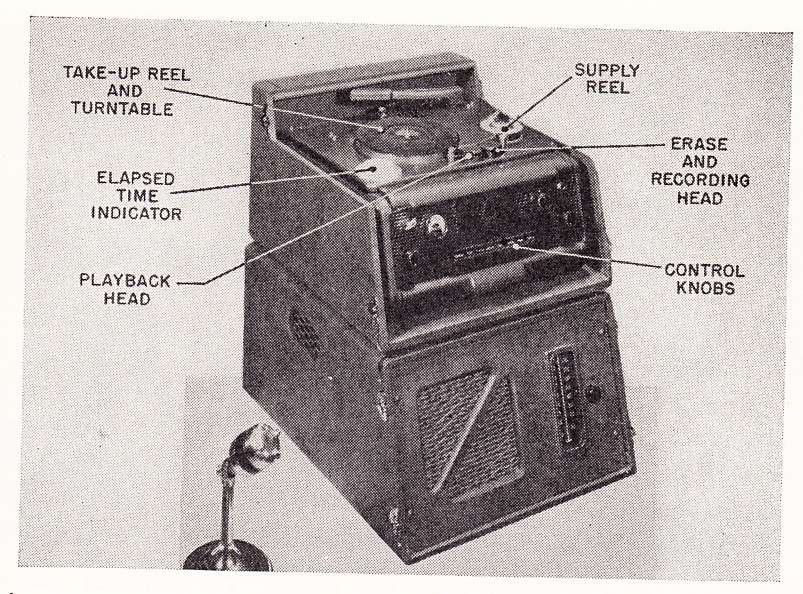

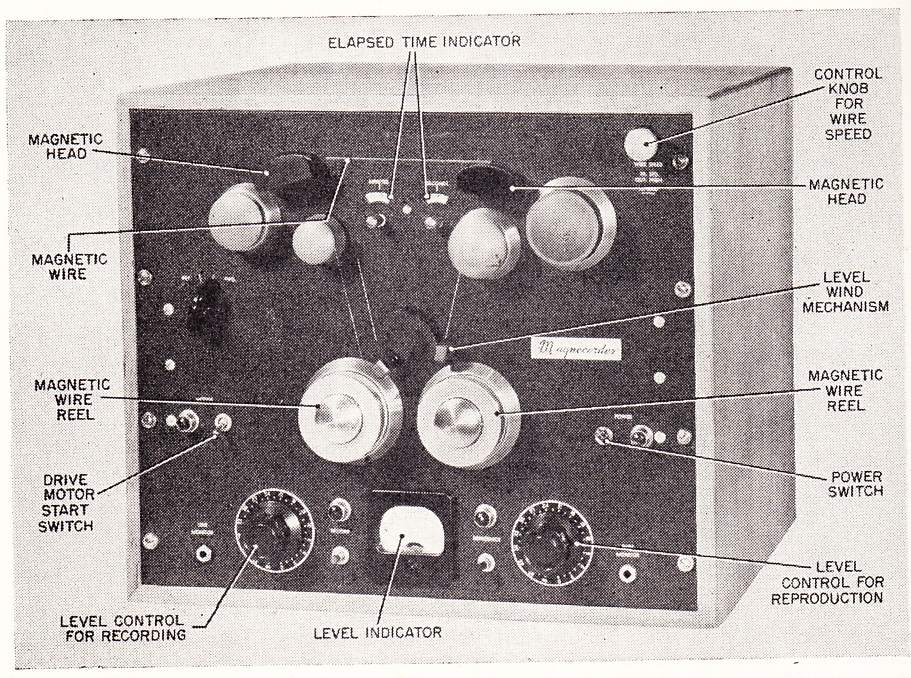

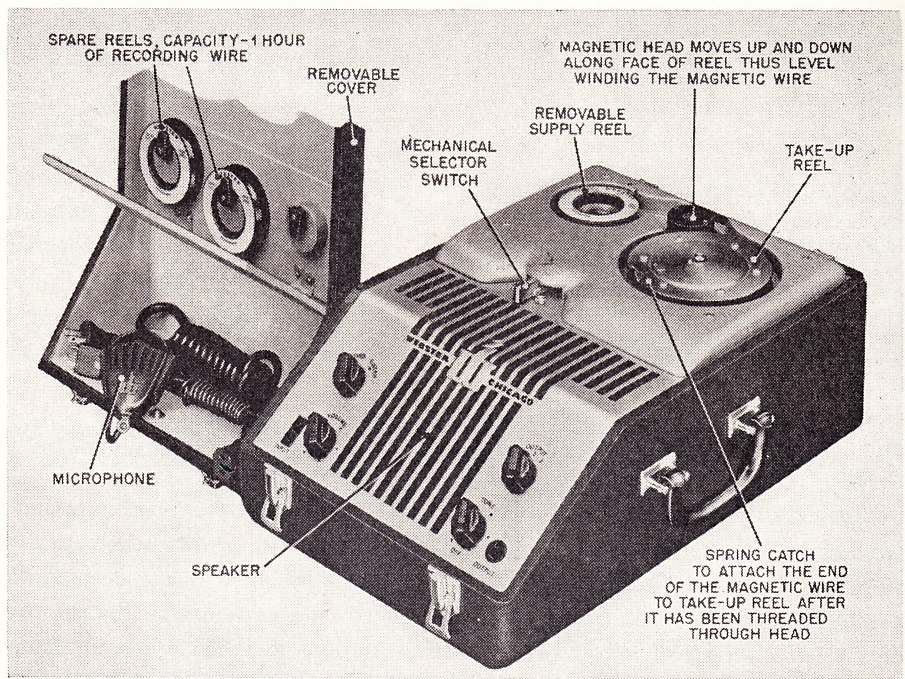

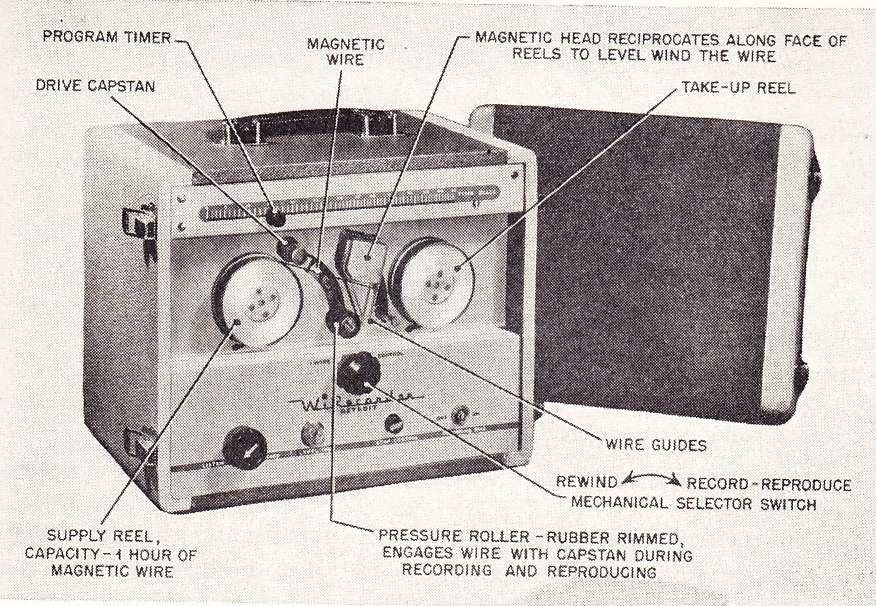

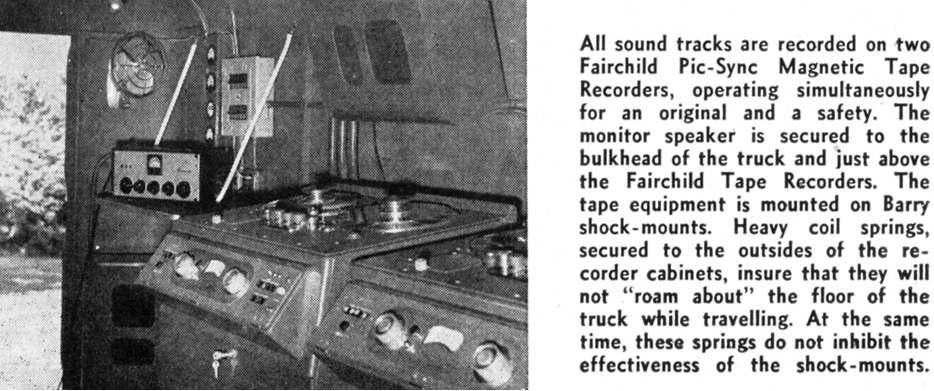

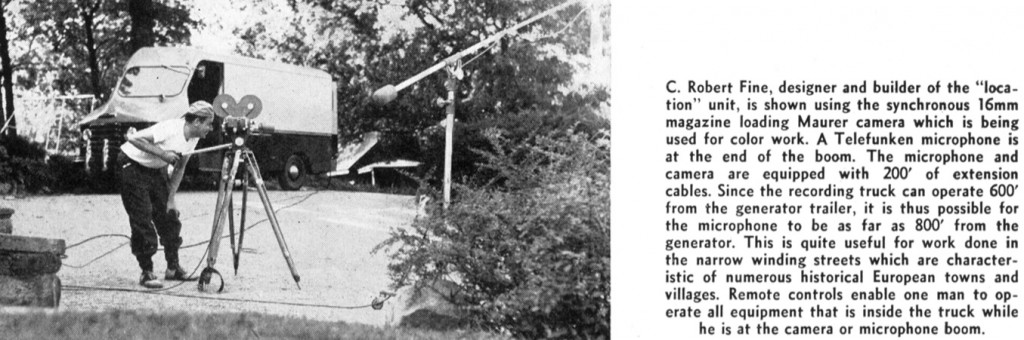

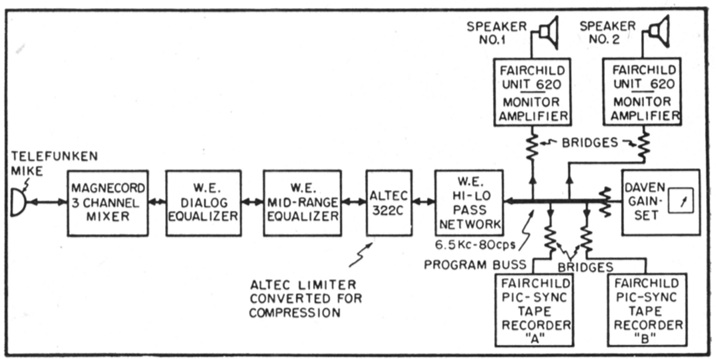

Above image/text from AUDIO ENGINEERING, Oct 1951 (no author attributed). Click here to download the complete article: AE-5110-Fine_Sound-reduced.

Above image/text from AUDIO ENGINEERING, Oct 1951 (no author attributed). Click here to download the complete article: AE-5110-Fine_Sound-reduced.

From Audio Engineering 10/51: “Mr. Fine’s assignment was to design and construct a completely mobile ‘location unit.’ With a thirty day deadline, the unit (…) was designed and constructed, laboratory and road tested, and driven aboard a freighter bound for Europe and its first assignment.”

Above: source: A/E, 10/51

Above: source: A/E, 10/51

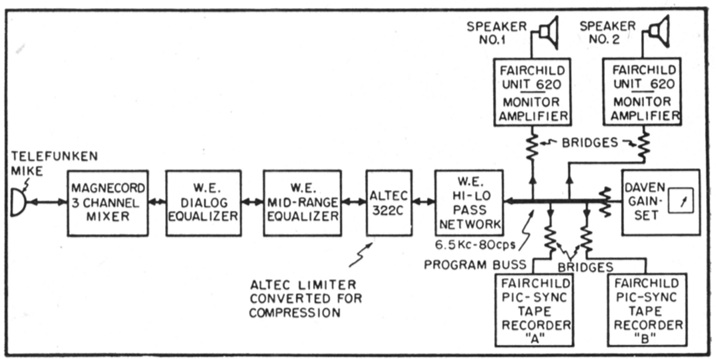

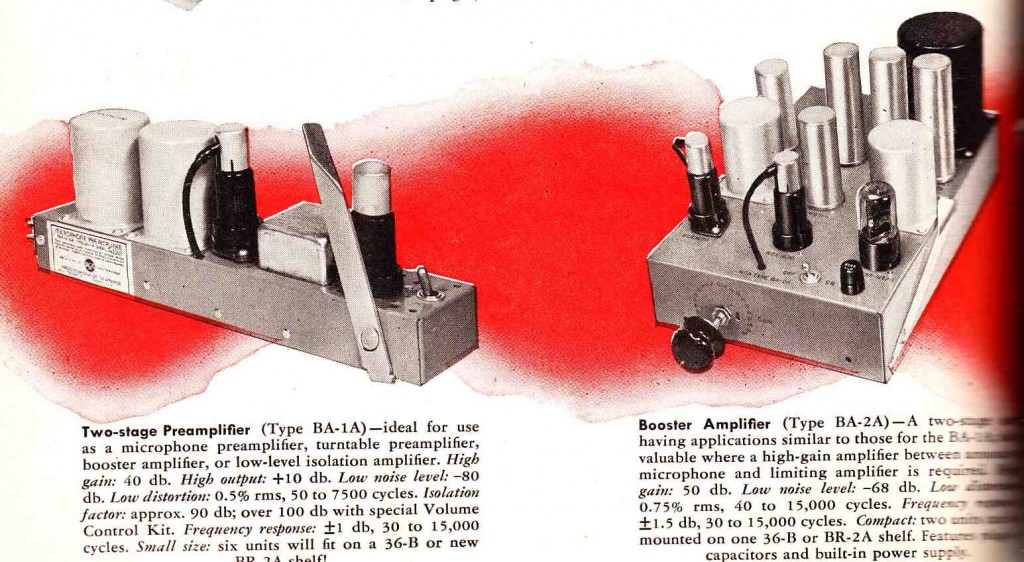

Tom Fine: “In its initial incarnation, the truck was outfitted to shoot 16mm or 35mm film with sound. There was a primitive 3×1 mixer and two Fairchild tape recorders which were locked to the camera via Fairchild’s Pic-Sync system.

Above: Cinecruiser equipment compliment c. 1951 (source: A/E, 10/51)

Above: Cinecruiser equipment compliment c. 1951 (source: A/E, 10/51)

“The Schweitzer film was eventually completed and went on to win the 1957 Oscar for Best Documentary Feature. The full film is available now for viewing on Vimeo.

“After completing production on the Schweitzer assignment, Hill generously loaned the truck out for Mercury Living Presence recording trips, beginning in 1952 in Minneapolis.

Above: photos by Bill Decker (via Tom Fine).

Above: photos by Bill Decker (via Tom Fine).

“The photos above show the truck in Minneapolis in 1954, during a hot day of recording. Bob Fine and Mercury recording director David Hall are seen sitting on the tailgate. The two photos above were shot by Bill Decker. Bill was a Rockland County neighbor of Bob Fine. Bill was hired on for almost all Mercury recording trips as the truck’s driver and on-site assistant to Bob Fine and associate engineer Bob Eberenz. Bill was also a photographer, and his images of Mercury recording sessions were used on album covers and CD booklets.

“Jerome Hill gave the truck to Bob Fine in the mid 50s, and it continued to be the Mercury mobile recording studio into the mid-60′s.

Above: the Truck re-outfitted with one of the earliest AMPEX 300 3-Track tape machines (right) c. 1956

Above: the Truck re-outfitted with one of the earliest AMPEX 300 3-Track tape machines (right) c. 1956

“Although it was initially called the ‘Cinecruiser,’ the truck did much more time as a regular music-recording truck than a sound-for-picture truck. It was used to make all of the on-location Mercury recordings from 1952 through 1965. It traveled to Europe (England, Austria, France, Italy) and to Russia in 1962.

“The photo above was shot by Harold Lawrence, Mercury’s Musical Director at the time. In the photo you can see my father getting scolded by a Moscow policeman for parking the truck on Red Square. They were driving toward the Tchaikovsky Conservatory after picking up the truck at a rail yard outside Moscow, and everyone wanted to snap photos at Red Square, so my father pulled over. CBS News captured footage of Mercury’s recording trip to Moscow which was edited into a feature story that ran on the CBS Evening News. Here is the full clip via YouTube:

“The photo above was shot by Harold Lawrence, Mercury’s Musical Director at the time. In the photo you can see my father getting scolded by a Moscow policeman for parking the truck on Red Square. They were driving toward the Tchaikovsky Conservatory after picking up the truck at a rail yard outside Moscow, and everyone wanted to snap photos at Red Square, so my father pulled over. CBS News captured footage of Mercury’s recording trip to Moscow which was edited into a feature story that ran on the CBS Evening News. Here is the full clip via YouTube:

*************

*******

***

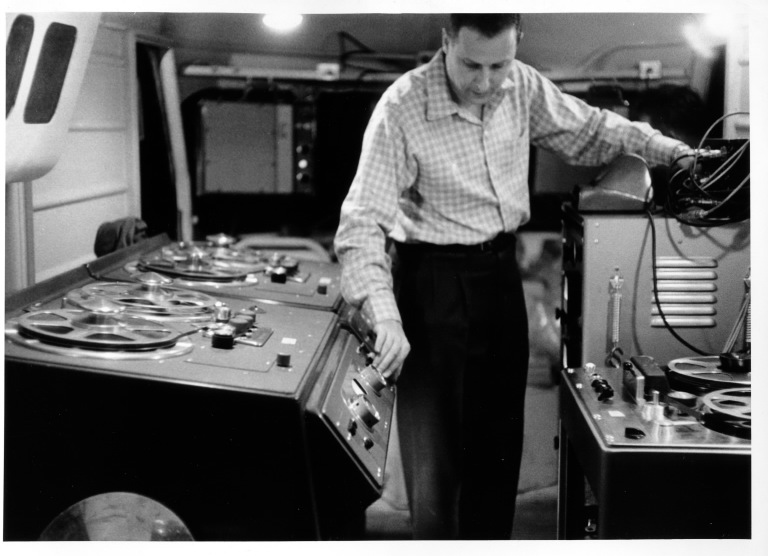

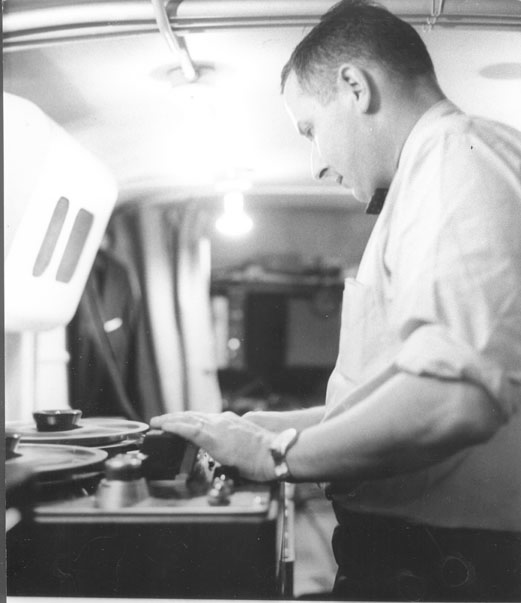

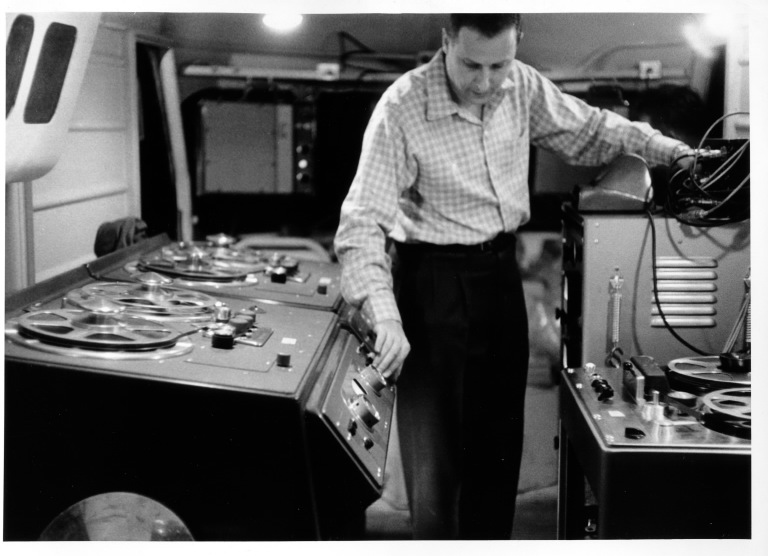

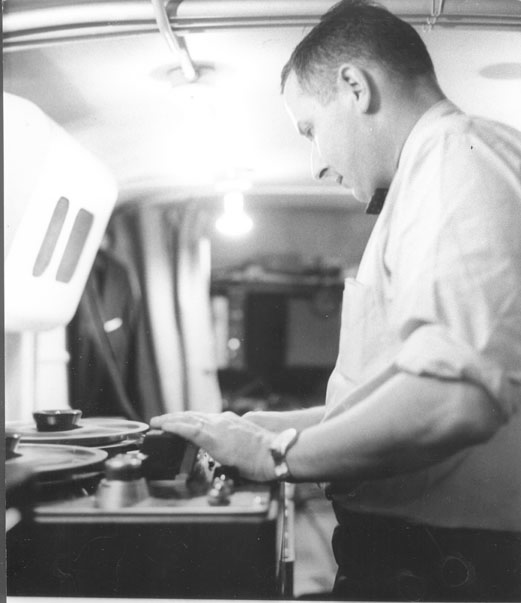

“The two photos above show Bob Fine in the truck in Italy in 1958. Mercury took the truck to Italy to make opera recordings in 1957 and 1958. The truck was rebuilt in 1958 and both Fairchild mono recorders were replaced by Ampex 300 full-tracks. From 1961-63, the truck also carried a Westrex 35mm magnetic film recorder to many Mercury Living Presence and Command Classics recording sessions.

“The two photos above show Bob Fine in the truck in Italy in 1958. Mercury took the truck to Italy to make opera recordings in 1957 and 1958. The truck was rebuilt in 1958 and both Fairchild mono recorders were replaced by Ampex 300 full-tracks. From 1961-63, the truck also carried a Westrex 35mm magnetic film recorder to many Mercury Living Presence and Command Classics recording sessions.

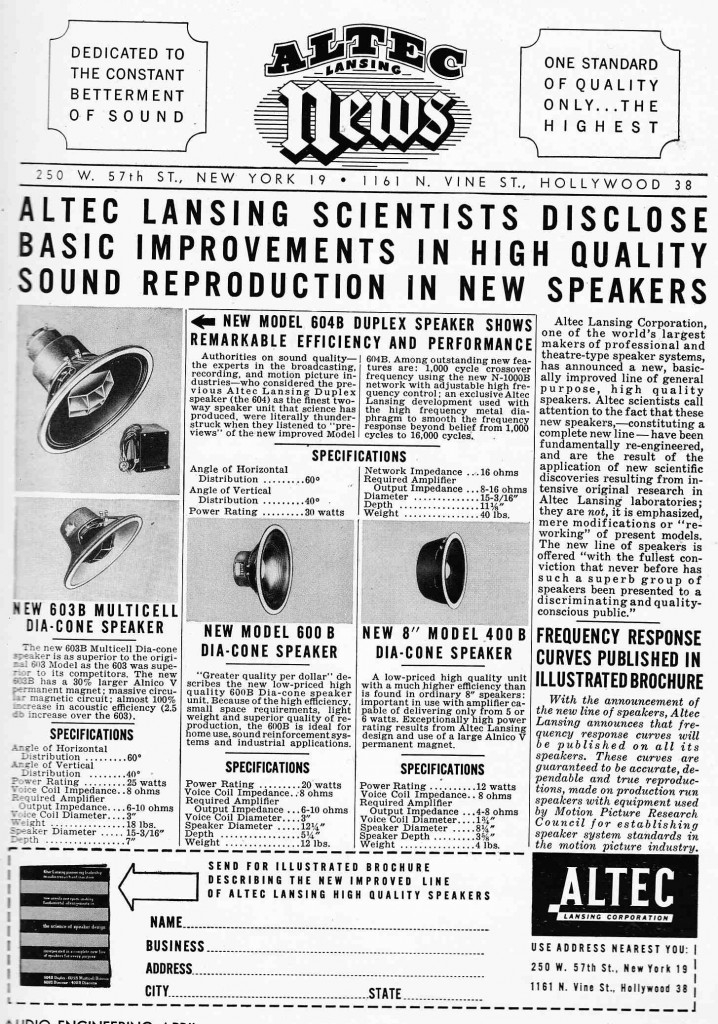

In the early days of the Mercury Living Presence series, the truck would carry at least two microphones (the main recording mic and its backup), ropes to hang the mics in the recording venue, the two Fairchild tape recorders, a single Altec monitor speaker and a McIntosh amplifier to power it and plenty of blank tape.

When stereo came along, the process got much more complicated: 3 mics plus spares (at least 6 mics), all the extra cabling and ropes, the two Fairchilds plus two Ampex 300-3 machines, three Altec A7 monitor speakers and three McIntosh amplifiers, an ingenious monitor-control system based on a surplus telephone stepper relay (the producer would use a rotary dial to call up the mics or whatever tape machine she wanted to hear in the speakers), and all the blank tape (and/or film) required.”

“In the photo above, Bob Eberenz adjusts the faders at a Detroit Symphony session in 1962 with the truck outfitted for 35mm magnetic film recording. At the time the truck was fitted for 3-track mag-film recording, 3-track 1/2″ tape, and full-track 1/4″ mono tape. Bob Eberenz was a native of Jackson MI, and was Bob Fine’s long-time ‘right hand man.’ Eberenz was hired at Fine Sound after previously having worked at Altec (then called All Technical Services), and at MGM’s Sound Department in Hollywood. Eberenz served as chief technical engineer at Fine Sound. He was later hired for Bob Fine’s second studio, Fine Recording (see previous article – ed), where he ran the maintenance and engineering department. Eberenz also rebuilt the recording truck in 1958.

“In the photo above, Bob Eberenz adjusts the faders at a Detroit Symphony session in 1962 with the truck outfitted for 35mm magnetic film recording. At the time the truck was fitted for 3-track mag-film recording, 3-track 1/2″ tape, and full-track 1/4″ mono tape. Bob Eberenz was a native of Jackson MI, and was Bob Fine’s long-time ‘right hand man.’ Eberenz was hired at Fine Sound after previously having worked at Altec (then called All Technical Services), and at MGM’s Sound Department in Hollywood. Eberenz served as chief technical engineer at Fine Sound. He was later hired for Bob Fine’s second studio, Fine Recording (see previous article – ed), where he ran the maintenance and engineering department. Eberenz also rebuilt the recording truck in 1958.

Above: Bob Eberenz sitting on the tailgate of the truck after it was rebuilt in the late 50s.

Above: Bob Eberenz sitting on the tailgate of the truck after it was rebuilt in the late 50s.

“As Fine Recording grew and got busier in the 1960′s, Eberenz became the main engineer on the Mercury Living Presence and Command Classics recording sessions. Often, Bob Fine would make the initial mic placements and fine-tune the setup to the satisfaction of the producer, then fly home to NY for a never-ending heavy schedule of recording sessions at the studio. Bob Eberenz would run the recording equipment for the entire on-location session and then see to it that the truck got back to NY in good shape.

“Eberenz left Fine Recording in 1967 and went on to work for two decades at the movie-sound equipment maker Magnatech, ending his career as President of that company.

“In the 1990s, Eberenz was instrumental in the Mercury Living Presence CD reissue project. He restored the Ampex 300-3 tape machine and Westrex 35mm magnetic-film machine, and rebuilt producer Wilma Cozart Fine’s custom 3-to-2 mixdown console, which was made out of Westrex modules.

*************

*******

***

Fine in Milan ’58

Fine in Milan ’58

“Just about every Mercury Living Presence recording made from 1952 through 1964 that wasn’t made at Fine Recording (in other words, about 90% of them) was tracked on the Recording Truck, as was every Command Classics recording made from 1961 to 1966.

“Probably the most famous Mercury records with the truck were the Moscow recordings of the balalaika orchestra and the Byron Janis piano concerto records with Soviet orchestras and conductors. Also of note: the two ‘Civil War’ deluxe 2-LP albums, which featured extensive sound-documentaries made with real civil war weaponry recorded by the truck at Gettyburg PA and West Point NY. And certainly not least, the mono and stereo ‘1812 Overture’ recordings by Antal Dorati and the Minneapolis Symphony, which also used real-deal 1812-era European cannons, recorded at West Point. Both versions of the ‘1812 Overture’ were Gold Records.

For Mercury alone, the truck logged as many as three months a year on the road from the late 50′s to the mid 60′s. Literally thousands of hours of tape rolled at Mercury sessions on the recording truck. The truck was retired from Fine Recording around 1966. It was donated to the Oradell NJ Explorer Scouts troop, and was last seen alive and working in the early 1970s”

************

*******

***

We’d like to express our thanks to Tom Fine for providing this important piece of sound-recording history. In addition to Tom’s father Bob having engineered the audio for so many of these historic recordings, Tom’s mother Wilma Cozart Fine produced the Mercury Living Presence series and oversaw its re-issue on digital You can learn all about the Mercury Living Presence re-issue series at this link.

One final note: The PRESTO recording corp offered an account of Bob Fine’s recording truck in their 1952 newsletter. You can download that piece by clicking here: Fine_Sound_Truck-presto_1952-150

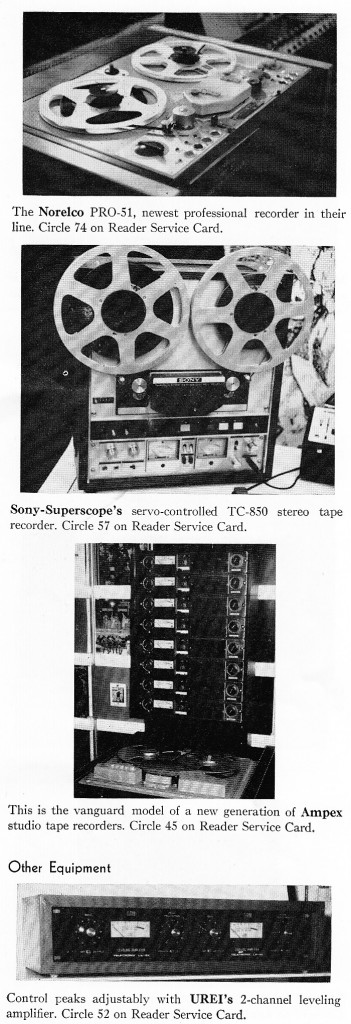

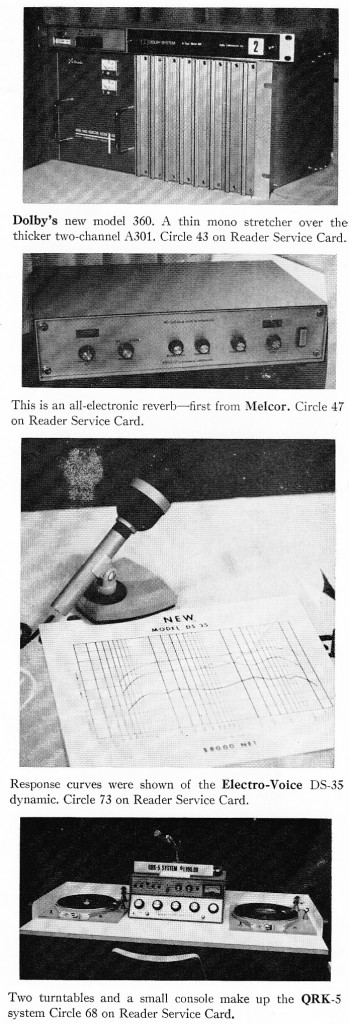

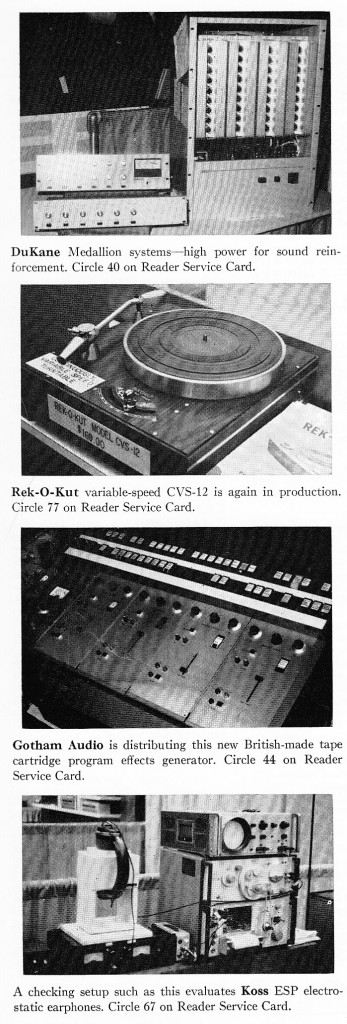

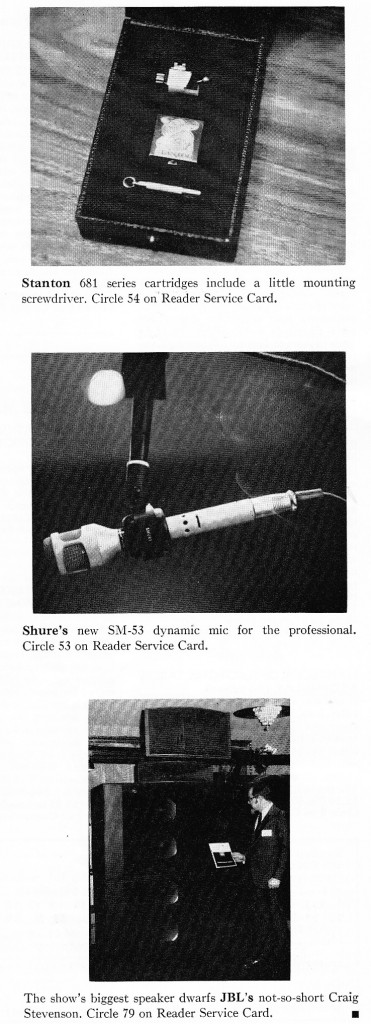

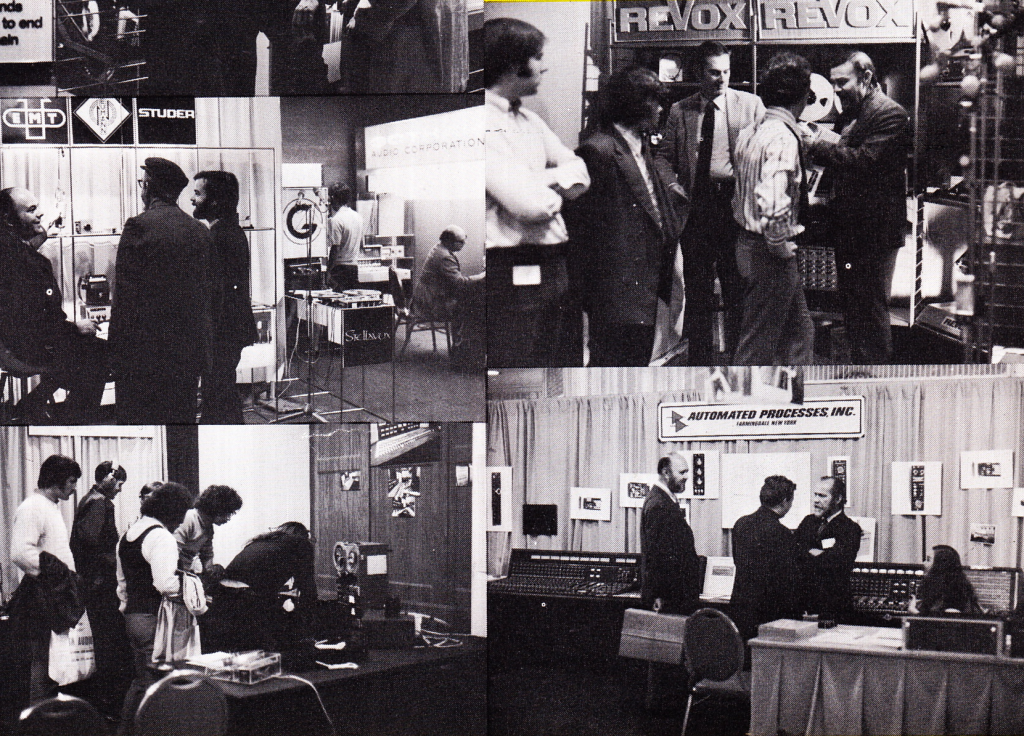

,,,and today, perhaps unsurprisingly: some of the new kit unveiled in 1971 at the NYC AES show, also via DB mag. Of note: Auto-Tec, Scully, Ampex and 3M intro’d new 16-track machines, Neve made a push for a new console (would this have been the series 80?), AKG introduced the BX-20 reverb, Melcor showed its model 5001 electronic reverb (anyone???), and a new company called Eventide introduced a digital pitch-shift device! The Neumann U47-fet and Sennheiser MHK-815 mics were introduced, as were the Marantz 500 and Crown M2000 power amplifiers.

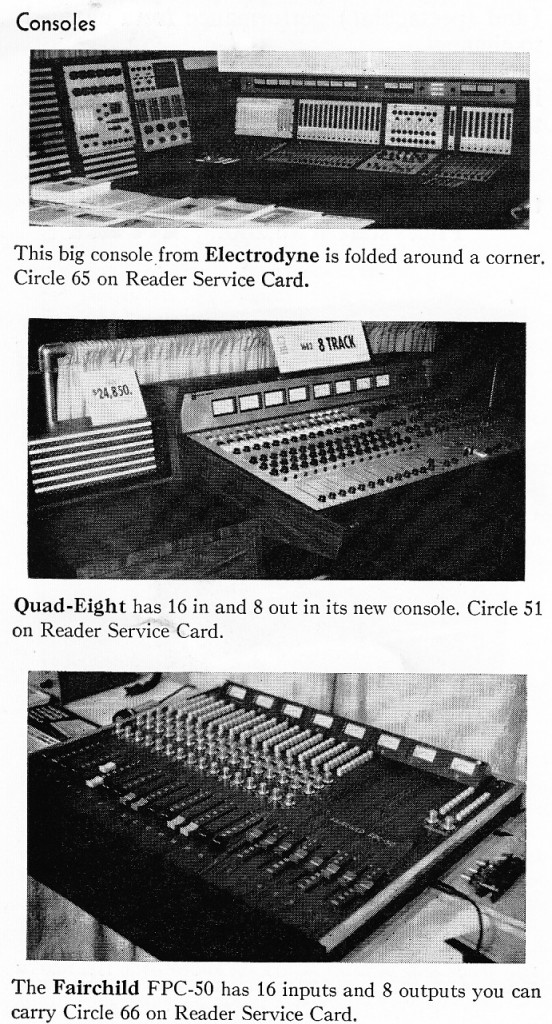

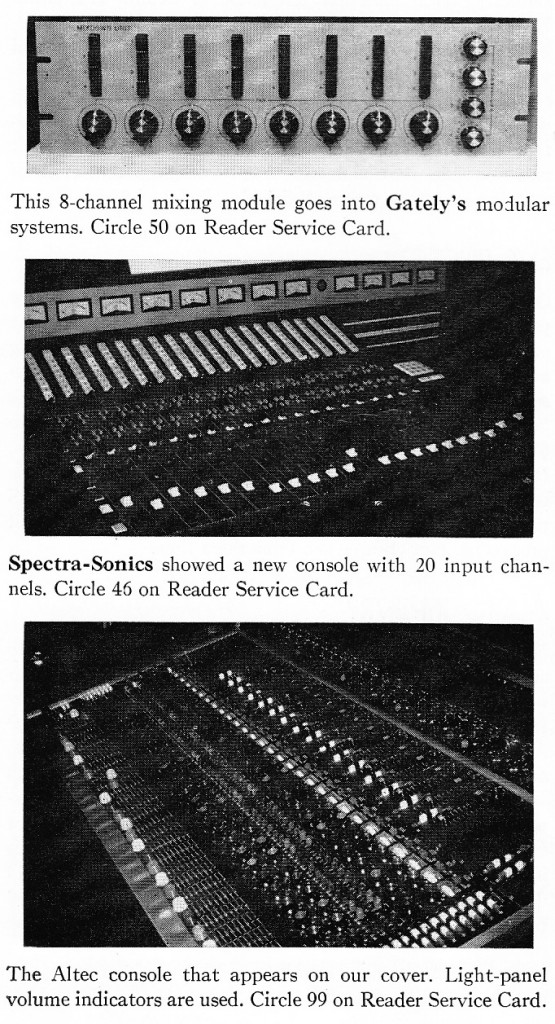

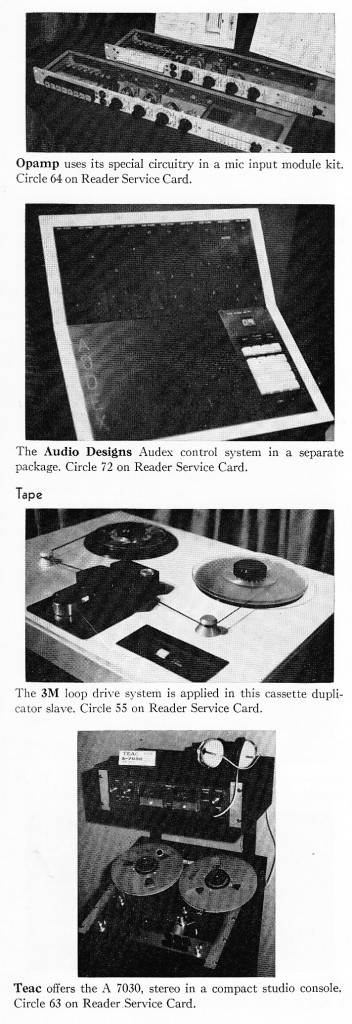

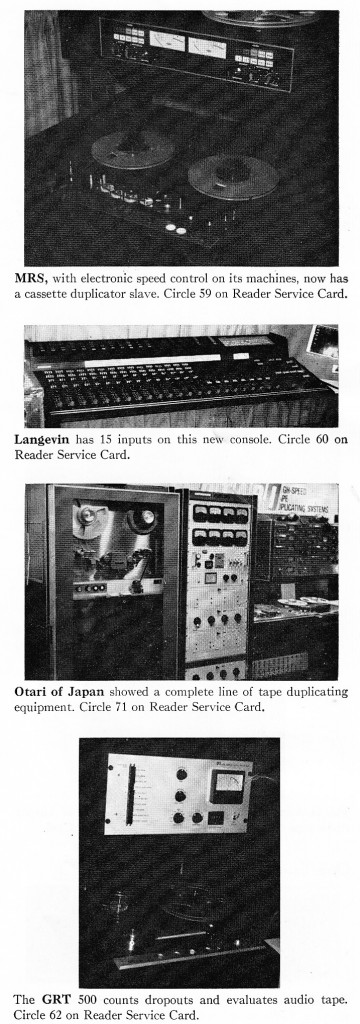

,,,and today, perhaps unsurprisingly: some of the new kit unveiled in 1971 at the NYC AES show, also via DB mag. Of note: Auto-Tec, Scully, Ampex and 3M intro’d new 16-track machines, Neve made a push for a new console (would this have been the series 80?), AKG introduced the BX-20 reverb, Melcor showed its model 5001 electronic reverb (anyone???), and a new company called Eventide introduced a digital pitch-shift device! The Neumann U47-fet and Sennheiser MHK-815 mics were introduced, as were the Marantz 500 and Crown M2000 power amplifiers.