Above: Reeves studio A during music scoring for “Louisiana Story,” a 1949 Oscar nominee for Best Writing, Motion Picture Story. The soundtrack score, composed by Virgil Thomson, won a Pulitzer Prize. L to R: co-director Frances Flaherty, conductor Eugene Ormandy, and C. Robert Fine, mixing engineer. (Source: T. Fine)

Above: Reeves studio A during music scoring for “Louisiana Story,” a 1949 Oscar nominee for Best Writing, Motion Picture Story. The soundtrack score, composed by Virgil Thomson, won a Pulitzer Prize. L to R: co-director Frances Flaherty, conductor Eugene Ormandy, and C. Robert Fine, mixing engineer. (Source: T. Fine)

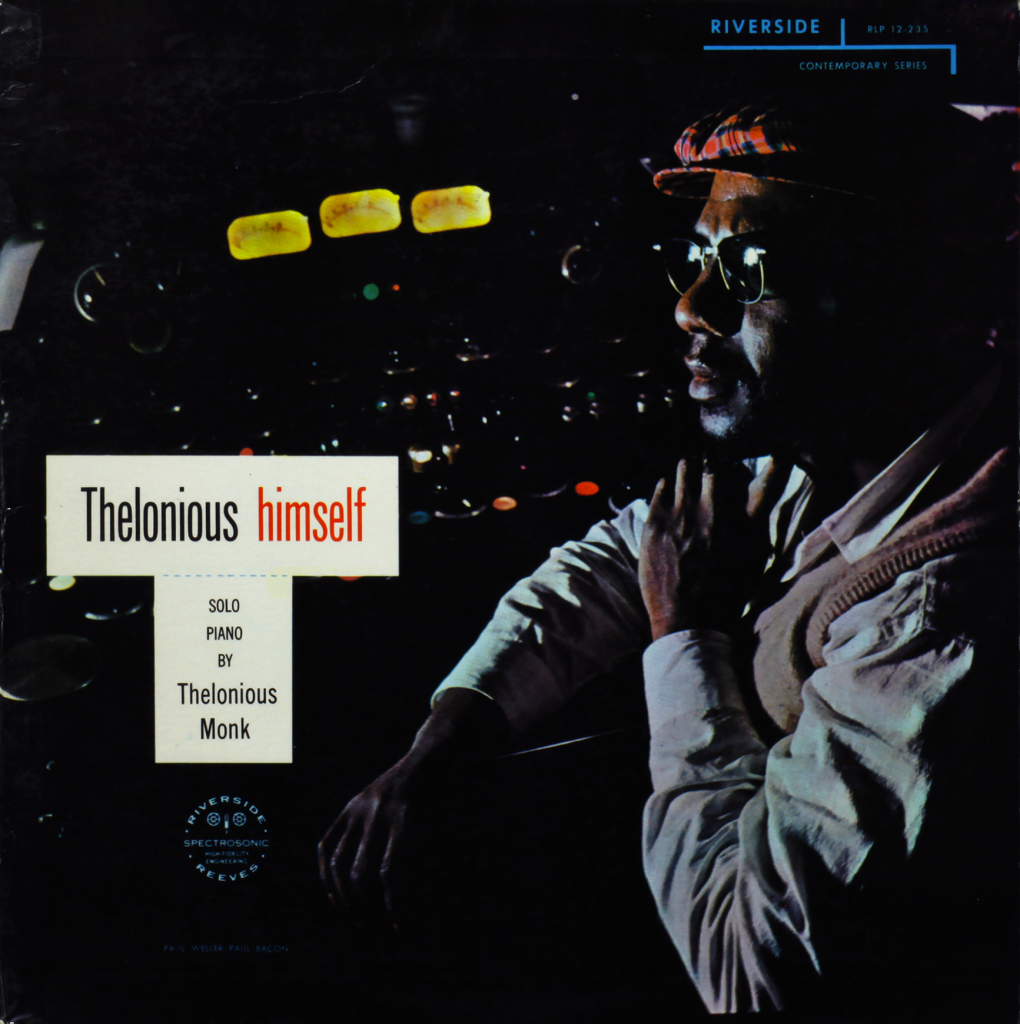

Considering that owner Hazard Reeves was the man responsible for introducing the magnetic soundtrack channel to motion-picture film, as well as being one of the developers of Cinerama, which prefigured both the stereo hi-fi music revolution and the IMAX film-format, there is surprisingly little information online regarding his Reeves Sound Studios (hf. RSS). RSS was in operation from approx. 1933 – 1980, and although it was primarily a sound-for-picture facility, some important albums were cut there, including early efforts by Thelonius Monk, Charlie Parker, and John Coltrane.

Monk listens to playback at Reeves c. 1956. Photo by E. Edwards.

Monk listens to playback at Reeves c. 1956. Photo by E. Edwards.

PS dot com contributor T. Fine has provided some background on this important piece of recording history. If any readers worked at RSS during its long history, please get in touch and tell us about it.

Above: soundtrack recording session for “Louisiana Story” in 1948. Eugene Ormandy is conducting the orchestra, with pickup via Altec 639 “Birdcage” microphones. (Source: T. Fine)

Above: soundtrack recording session for “Louisiana Story” in 1948. Eugene Ormandy is conducting the orchestra, with pickup via Altec 639 “Birdcage” microphones. (Source: T. Fine)

RSS opened its doors in 1933 (source: NYT). The earliest detailed account we have of its actual operation is a 1949 article by one Leon A. Wortman.

Click here to download a PDF of the article: Wortman-Fairchild_Studio_Design-low

Wortman’s piece(s) was originally published in the trade publication “FM AND TELEVISION” and subsequently re-published for promotional use by the Fairchild Recording Equipment Corporation. T. Fine: “Reeves (Sound Studios) was full of Fairchild and Langevin gear. Buzz Reeves was good friends with Sherman Fairchild.”

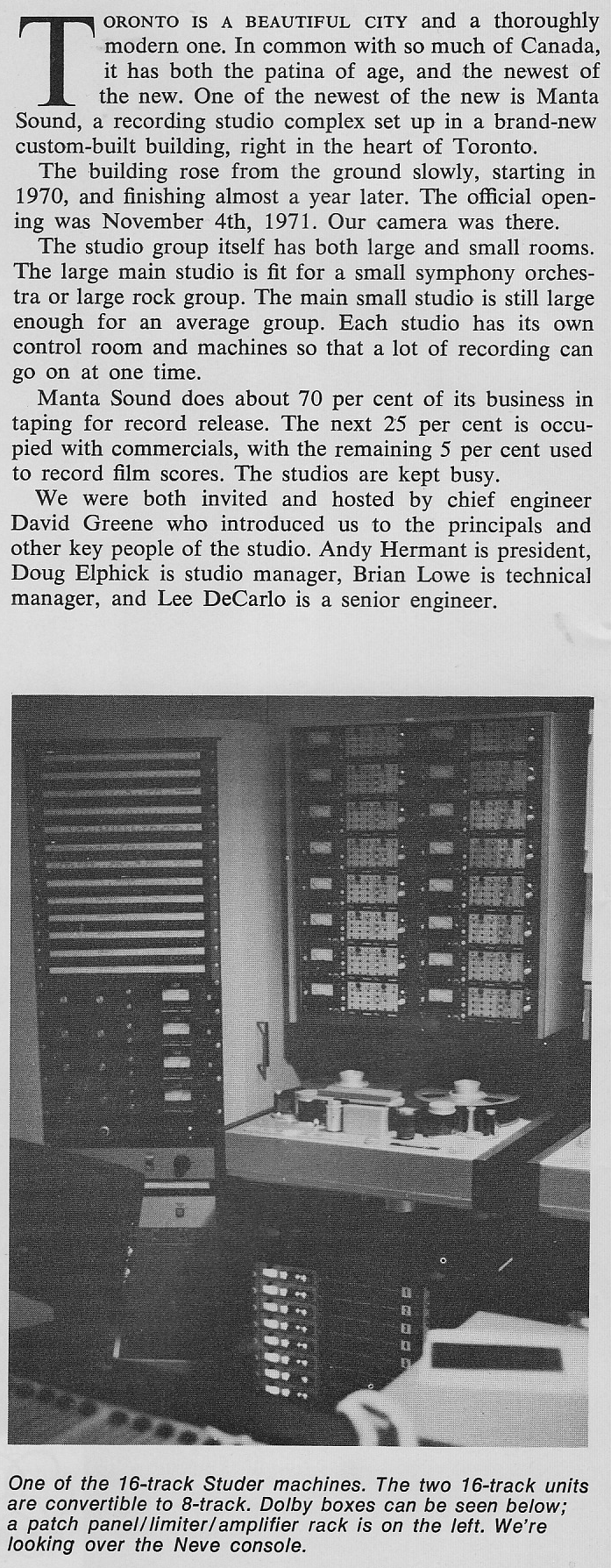

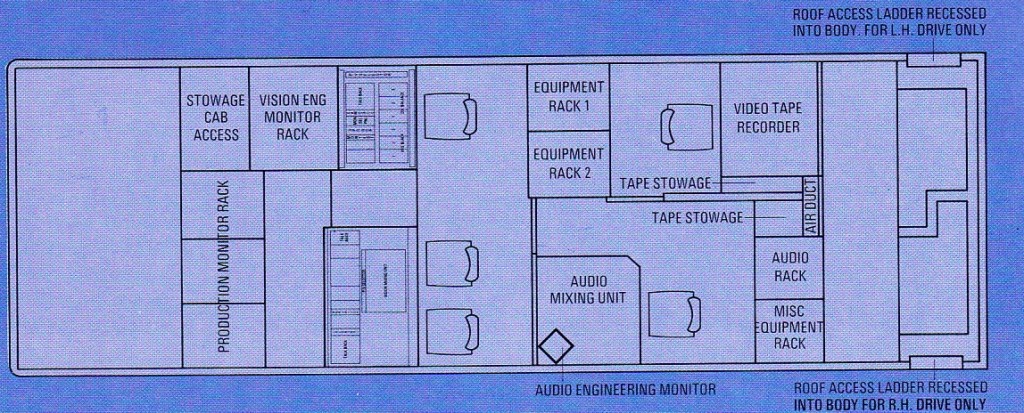

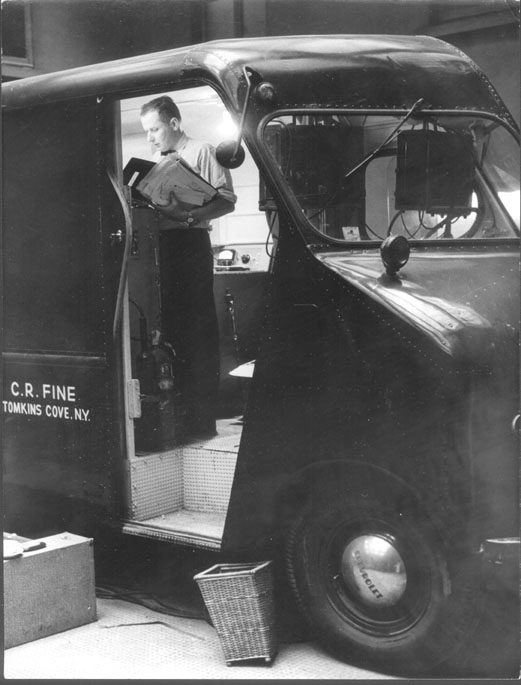

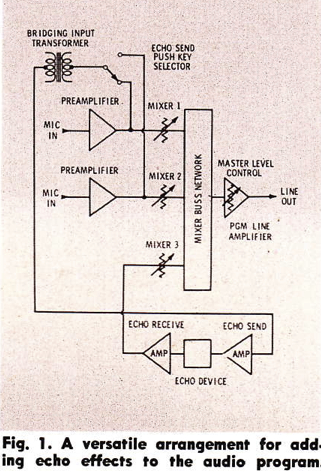

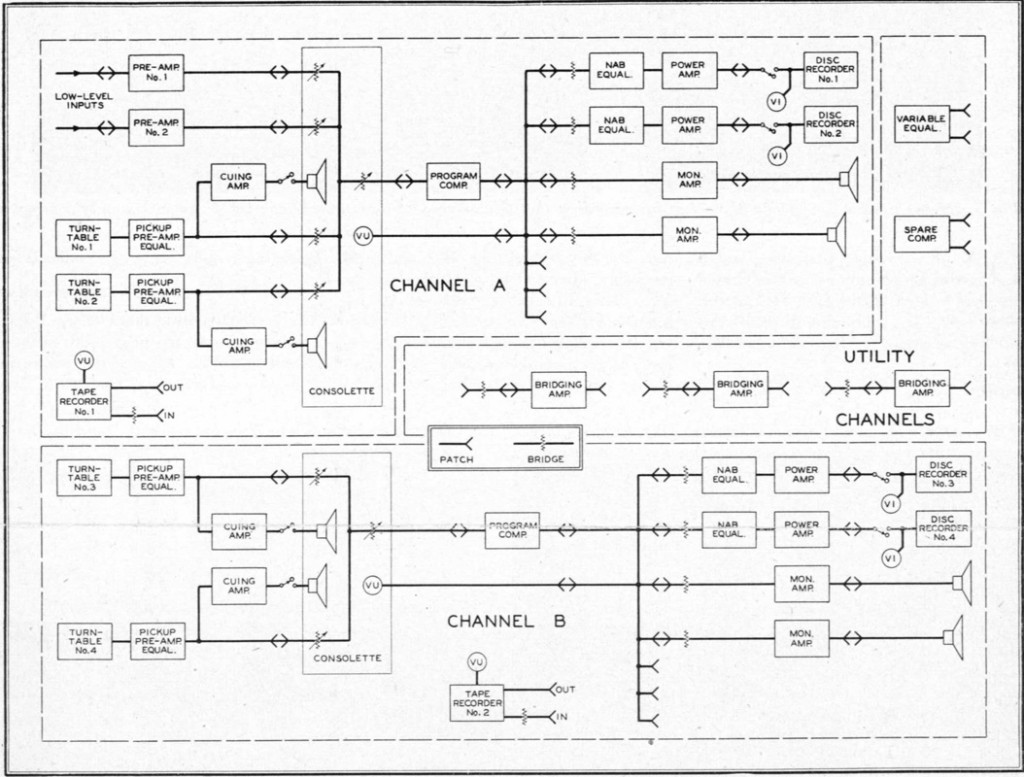

Above: schematic for RSS circa 1949 (Wortman)

Above: schematic for RSS circa 1949 (Wortman)

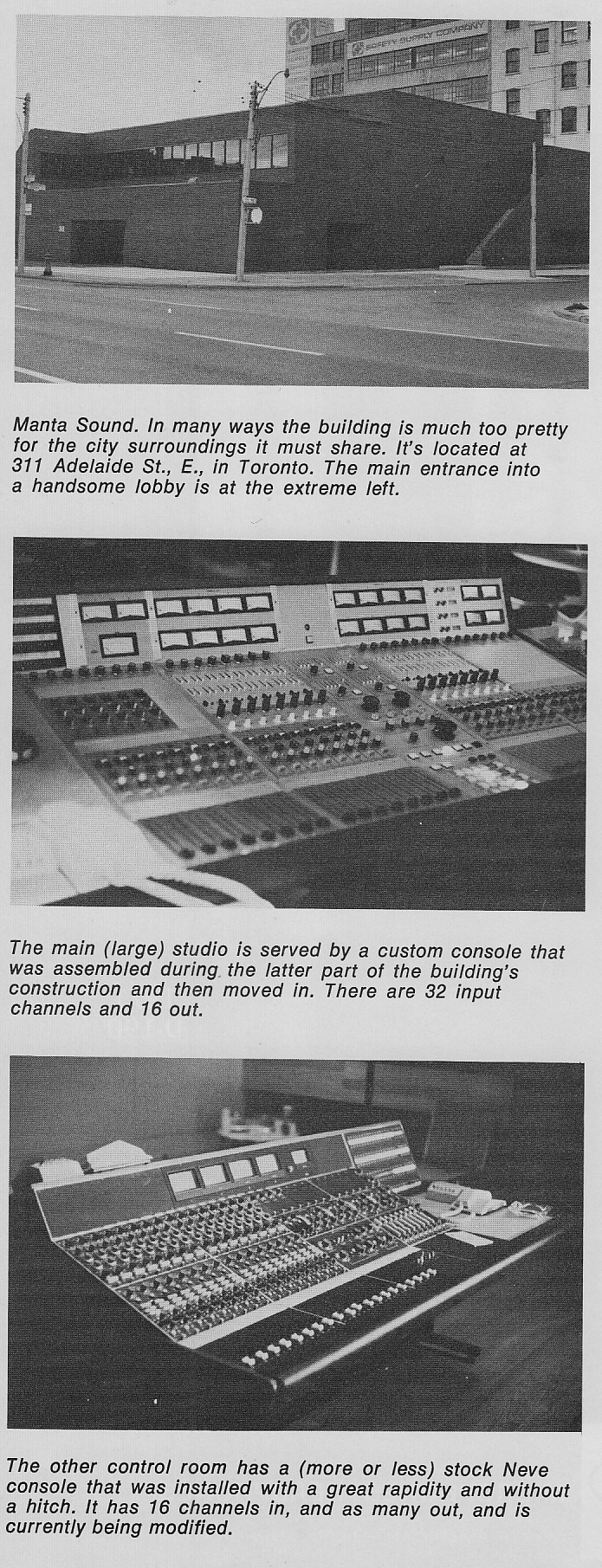

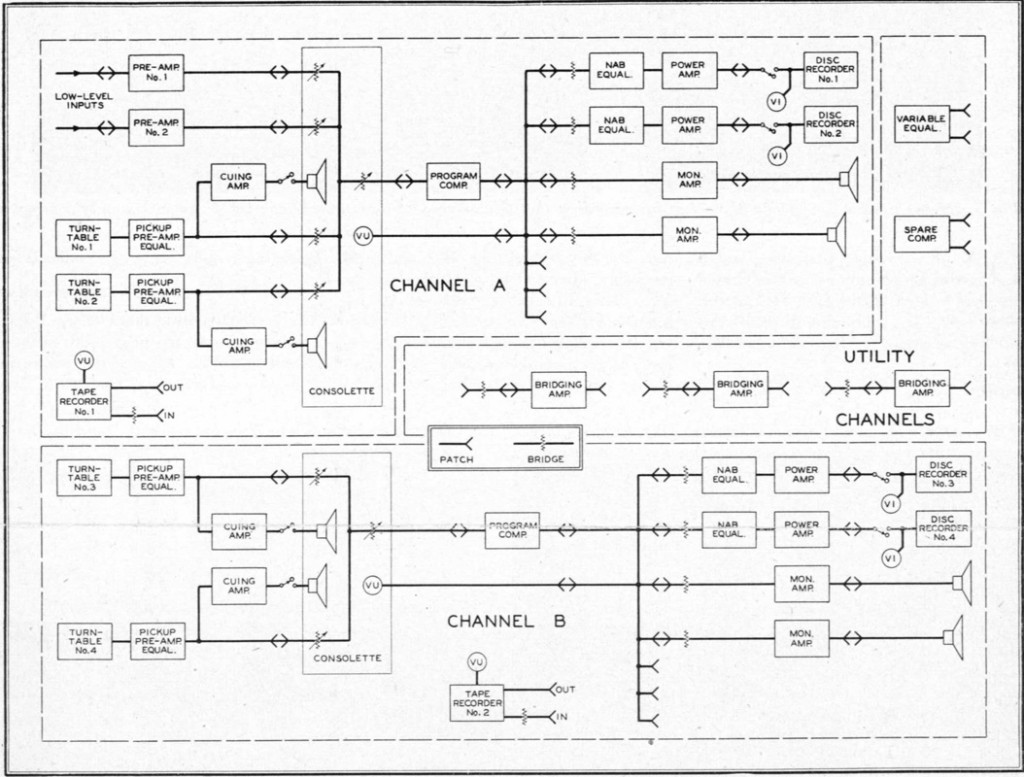

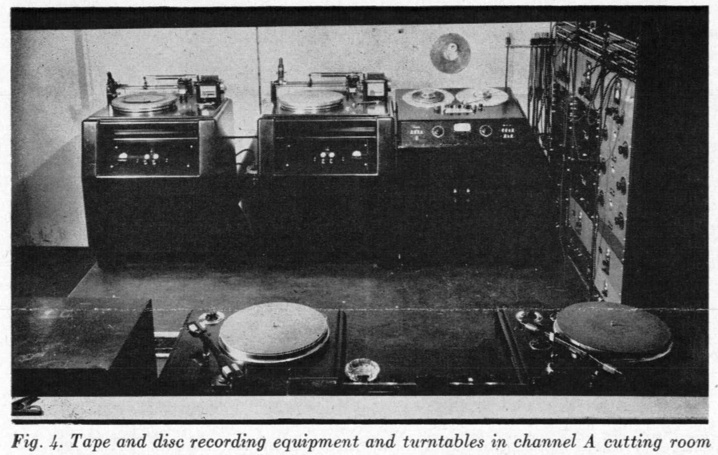

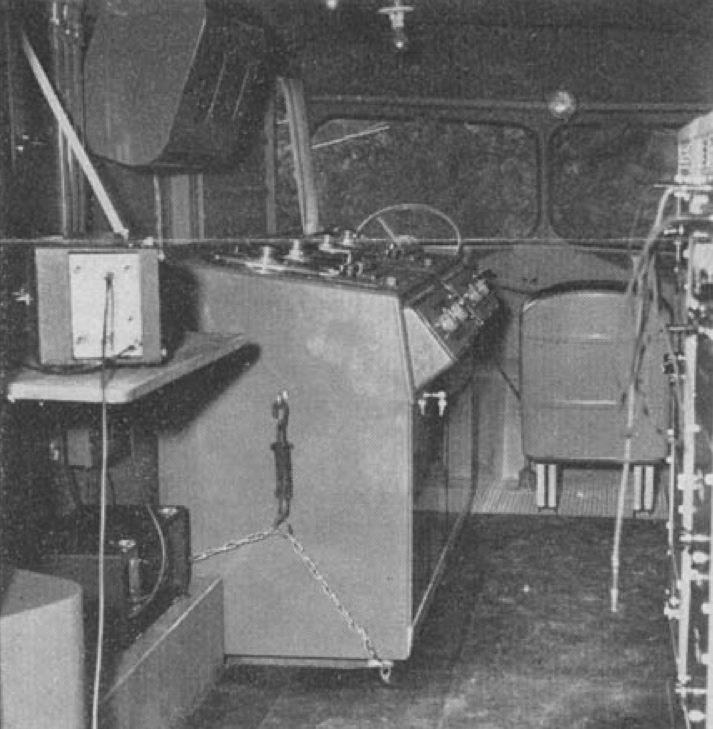

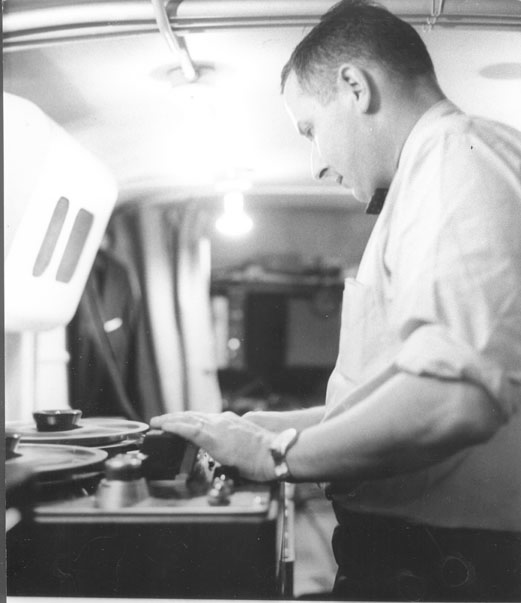

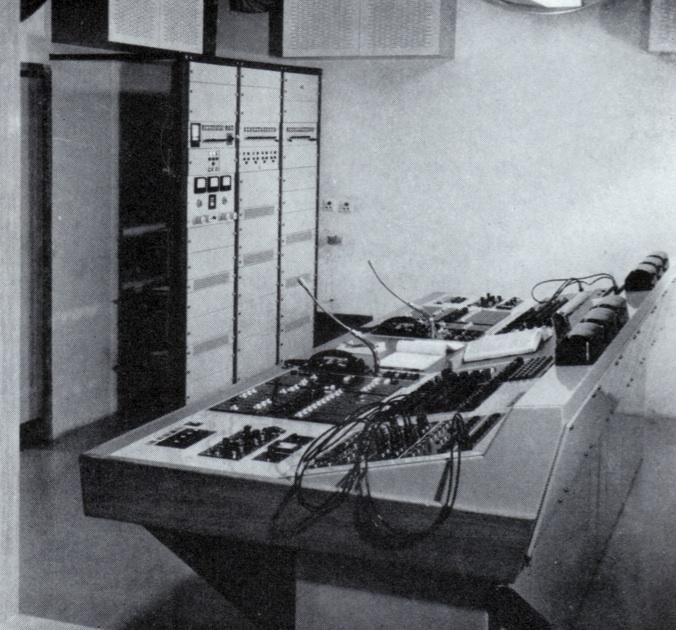

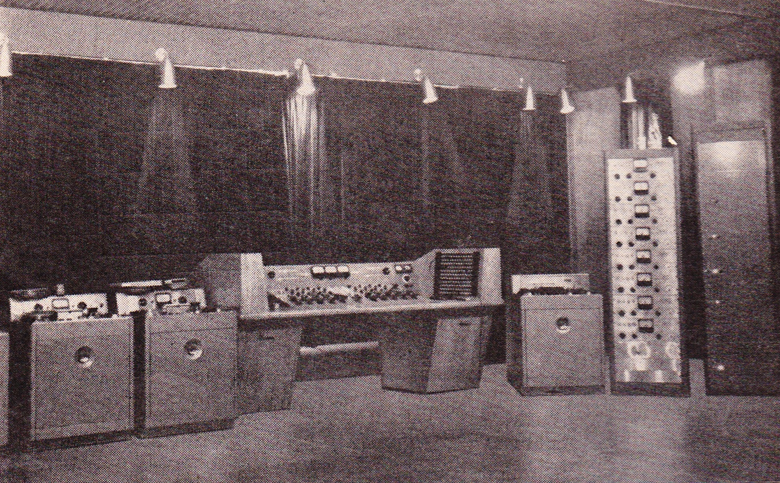

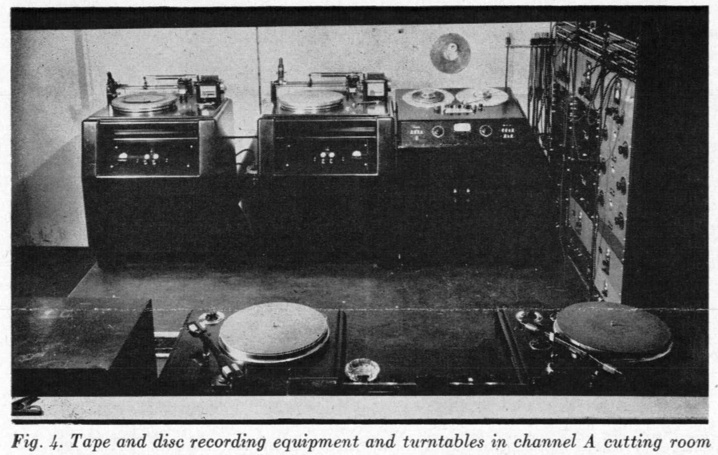

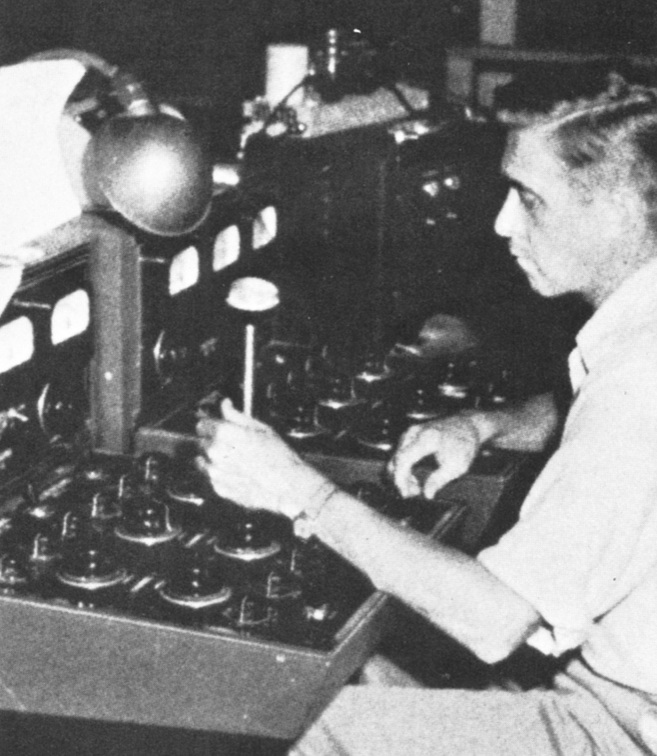

Reeves’ Room B c. 1949 (both above from Wortman)

Reeves’ Room B c. 1949 (both above from Wortman)

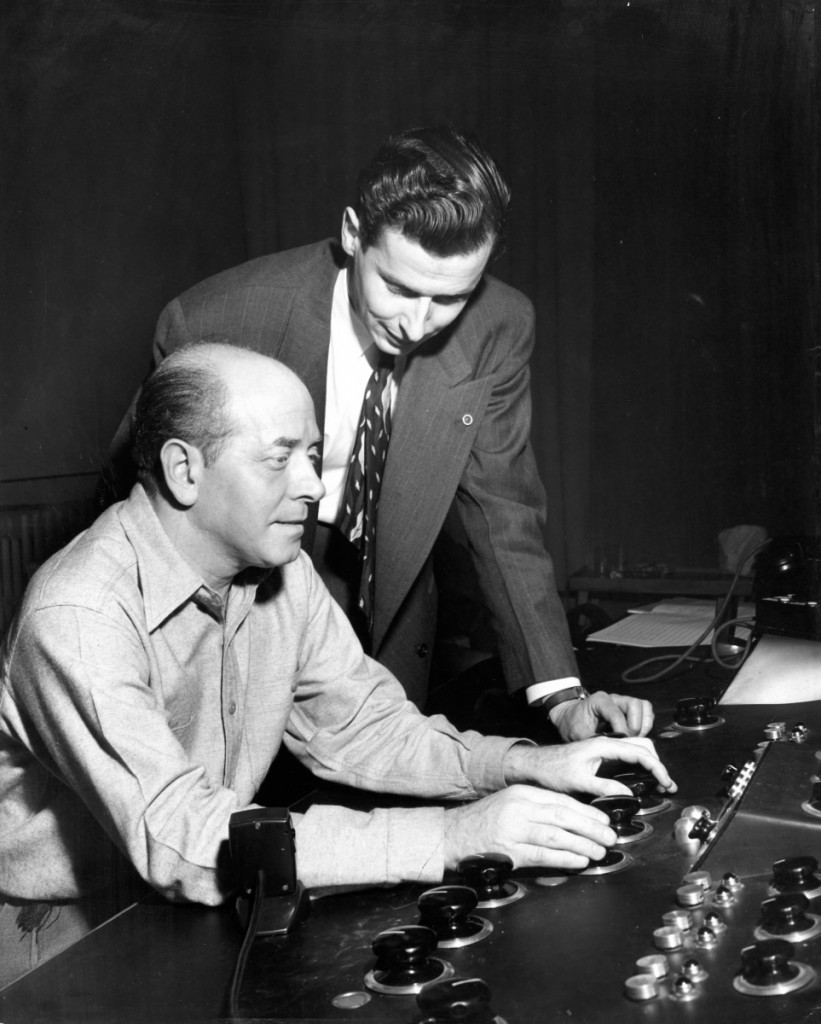

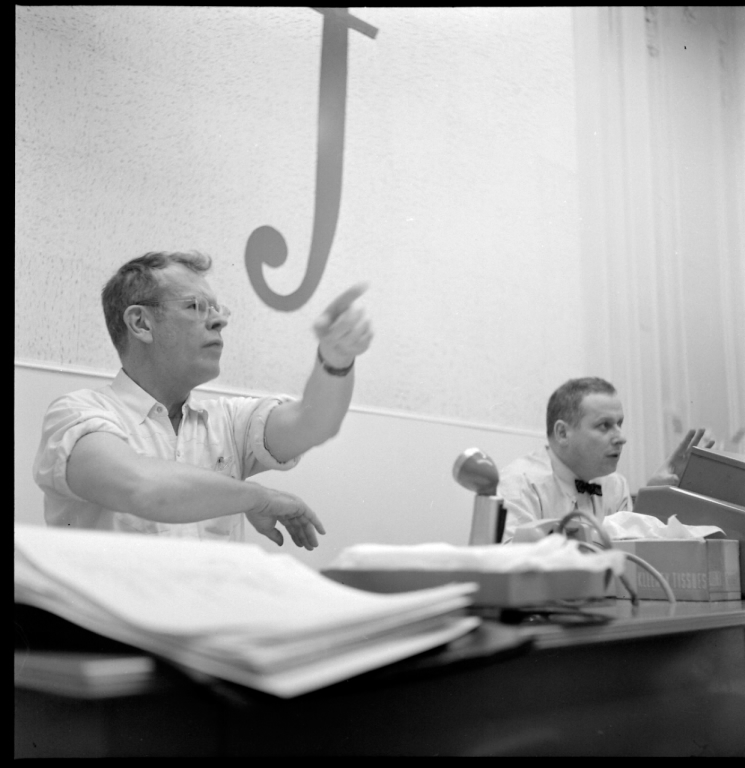

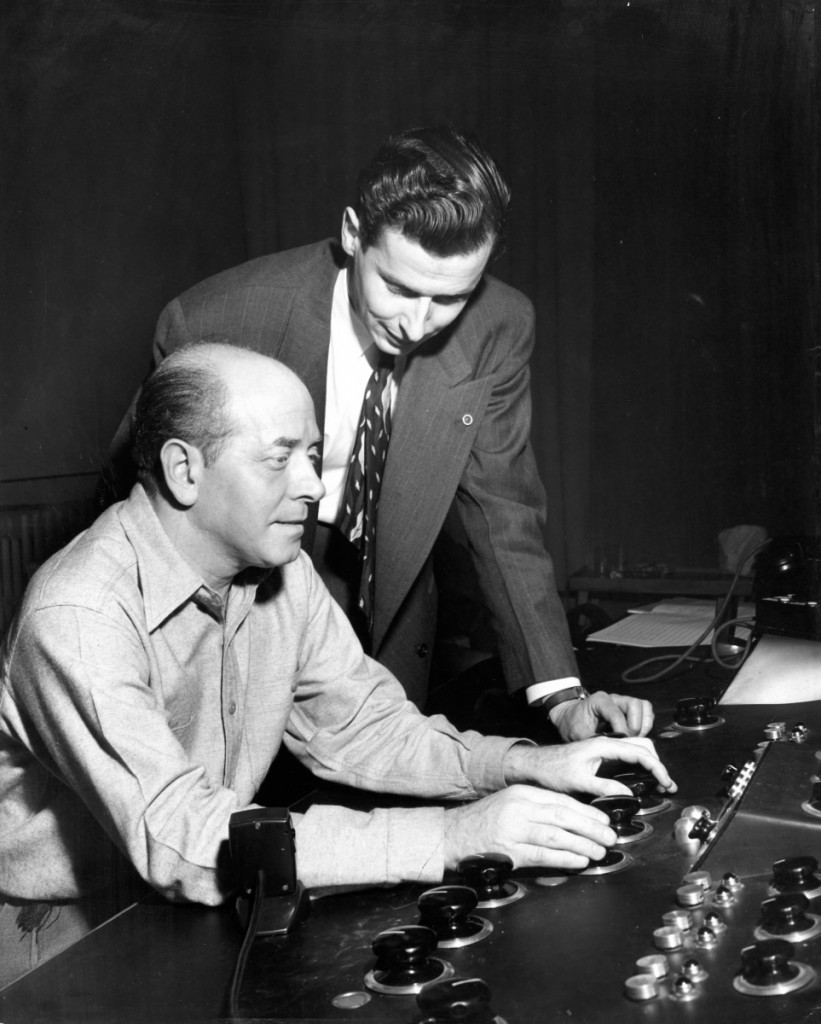

Above: Eugene Ormandy (L) and Bob Fine (R) work the Davens at RSS in 1948 (source: T. Fine)

Above: Eugene Ormandy (L) and Bob Fine (R) work the Davens at RSS in 1948 (source: T. Fine)

T. Fine: “During the time my father worked for Hazard “Buzz” Reeves in the late 40s, he engineered jazz and classical records for Mercury and Norman Granz (who later founded Verve Records). Among the significant jazz recordings were “Charlie Parker with Strings,” some sides in Granz’s deluxe “The Jazz Scene” album, and Charlie Parker’s latin-jazz sides with Machito on Mercury. Among the classical recordings for Mercury was the first U.S. use of the Neumann U-47 mic for orchestral recording: William Schuman’s “Judith” and “Undertow” performed by the Louisville Orchestra with Robert Whitney and William Schuman conducting.

“Here is a cut from the “Charlie Parker with Strings” sessions, followed by Charlie Parker with Machito and his Orchestra.

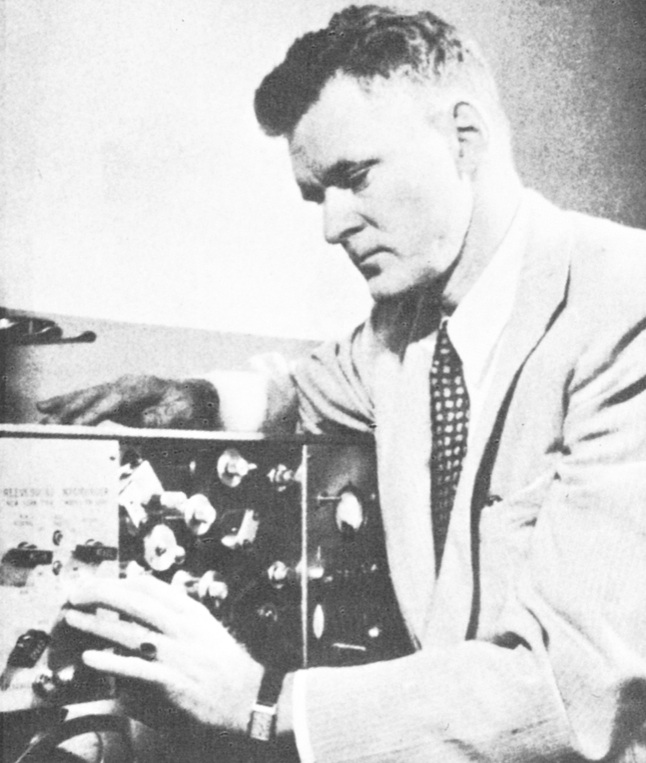

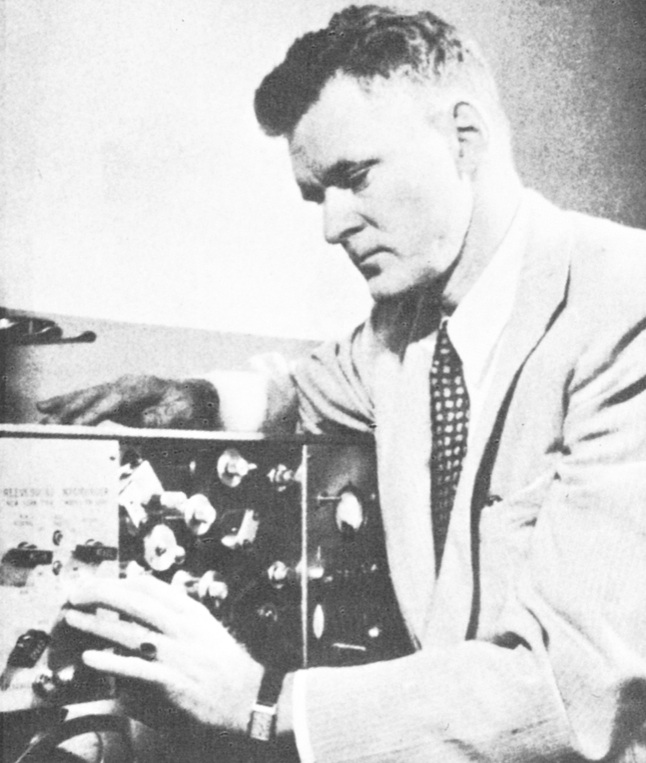

Above: Bob Fine in the Reeves A cutting room, 1949.

Above: Bob Fine in the Reeves A cutting room, 1949.

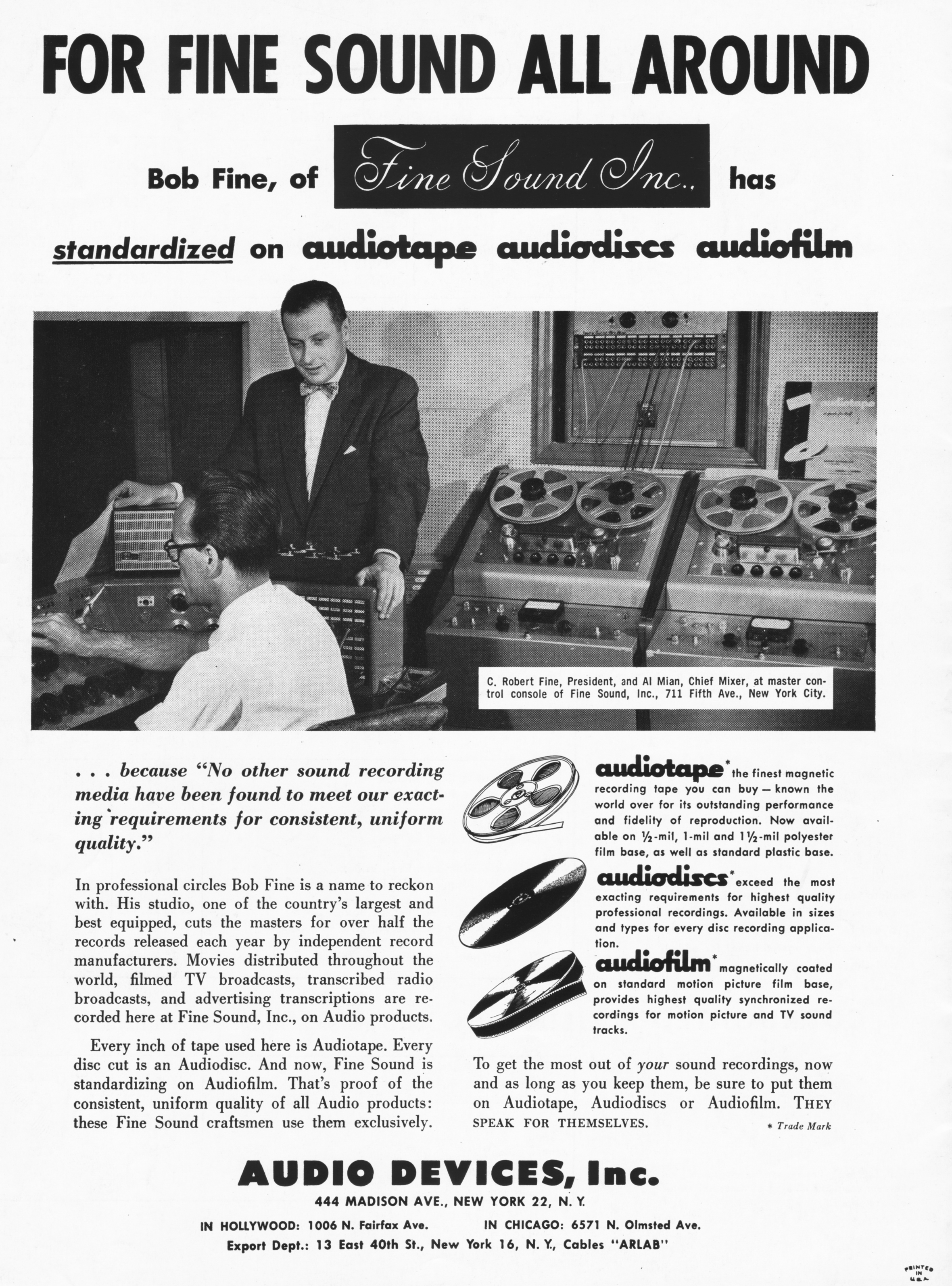

Ed: Bob Fine would leave RSS in the early 1950s to build his own sound studio Fine Sound, which was purchased and then closed by Loews/MGM. In 1958, Bob Fine opened Fine Recording Studios on 57th Street. You can read our account of Fine Recording Studios here and here.

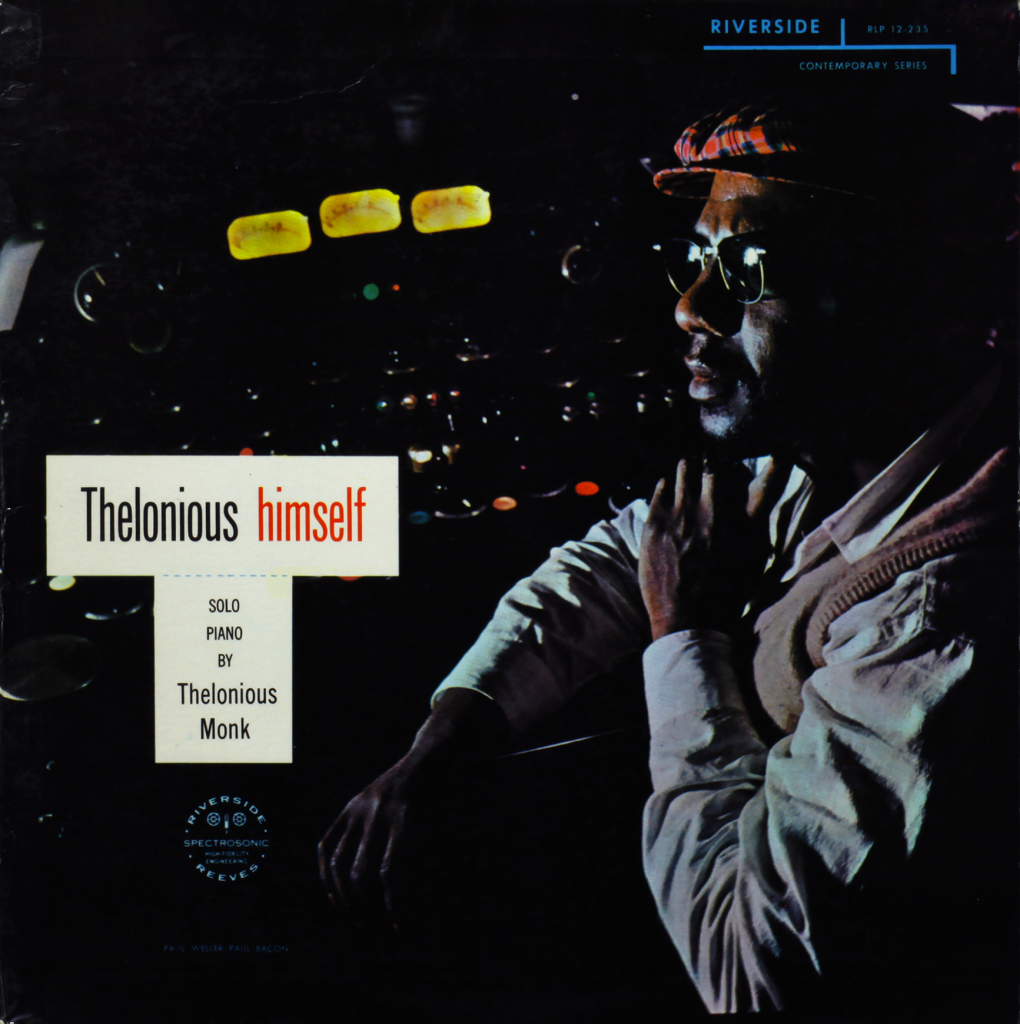

T. Fine: “In the 50s, Reeves was the studio for a bunch of significant Riverside Records jazz recordings.

In a 2007 interview, Riverside founder/producer Orrin Keepnews (who’s still alive and in his 90s) talked about making a deal with Buzz Reeves to get the studio and engineer overnight at a cut rate if he block-booked chunks of days.”

“Not long after (1954), we made a long-term deal for a studio that was of great value to us.. (We) had become aware of Reeves Sound Studios in the East 40s. It was a big room—although easily brought down by screens and baffles to the small-group size we basically needed. The studio was used primarily for radio jingles and other advertising agency work. That meant it was rarely in use after daytime working hours. They agreed to give us almost unlimited time for a very low annual flat fee, provided our recording was basically done at night. It was a real meeting of needs. That low studio rate, and the quite reasonable union scale rates in that far-off deflationary period, made it possible for us to do a lot of recording with very little cash, which was a pretty essential factor in the early growth of Riverside.” (source)

T. Fine: “It was perfect for jazz because Keepnews would have the guys come by to record after their club dates. He got a more relaxed but still tight feel than some of the Blue Note and Prestige sessions at Van Gelder, where the guys would often show up in daytime hours, off-kilter from their night-owl schedules.

“Reeves figured so prominantly in Riverside’s viability that some first-edition Riverside LP covers included a little graphic on the front boasting of “Riverside Reeves Spectrosonic High-Fidelity Engineering.” In the early stereo era, the “Stereosonic” replaced “Spectrosonic” in the logo.

“According to the Riverside Records discography located here, the sessions at Reeves began in late 1955 and continued until 1961.

(SOURCE)

(SOURCE)

*********

***

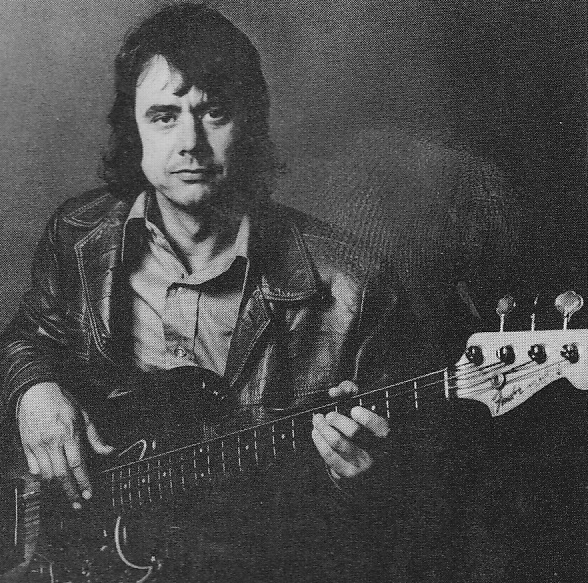

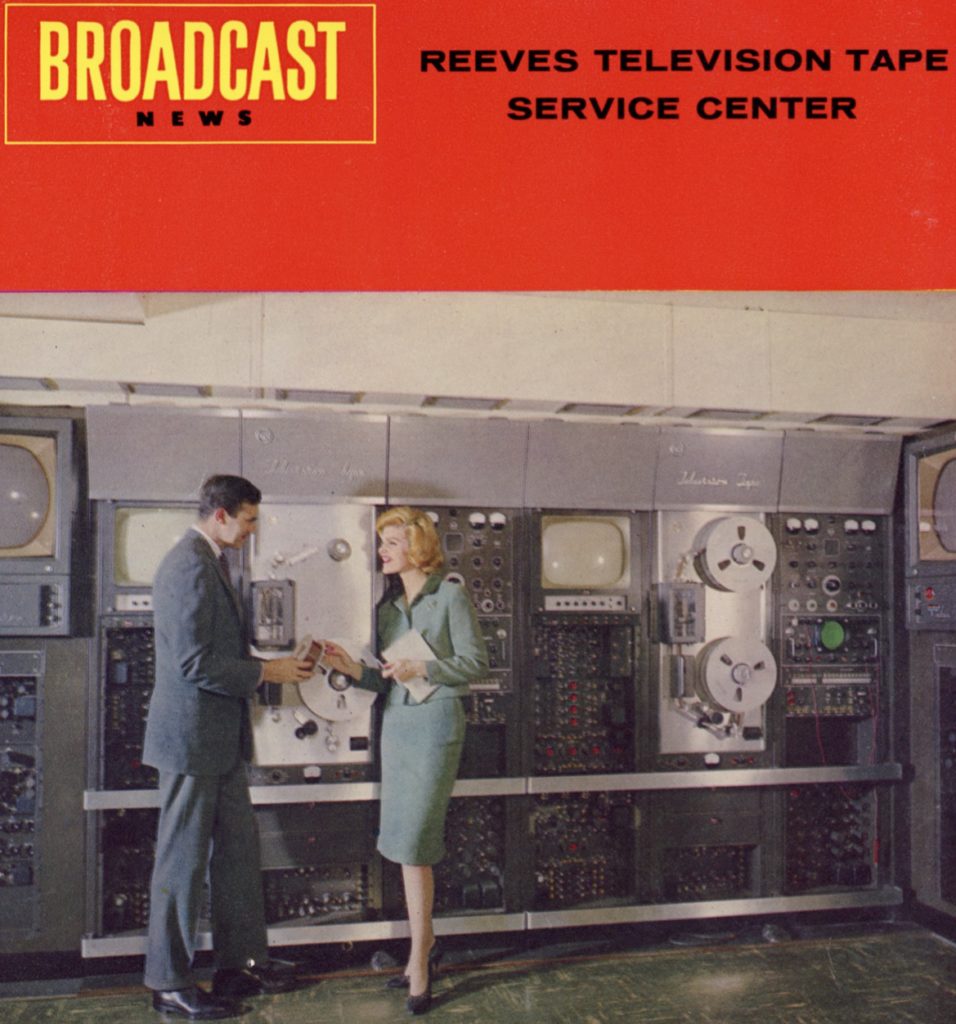

T. Fine: “In the 60s, Reeves turned more to sound-for-picture work, and they were an early TV-sound production center in NY. They later did a lot of sound mixing for videotaped productions, especially with WNET Public TV. Reeves bought out Fine Recording in the early 70s, and Bob Fine then managed Reeves Cinetel Studios in the early 70s. One of the projects he worked on then was producing the sync’d sound masters for the simulcasts of Don Kirschner’s “In Concert” late-night weekly rock concert series.”

“RSS produced a 4-track 1/2″ tape that was sync’d to video by a 59.95 Hz signal on one track, stereo audio (fed to the simulcasting FM station) on two tracks and mono audio to feed the TV station audio (or mono radio) on the 4th track.”

*********

***

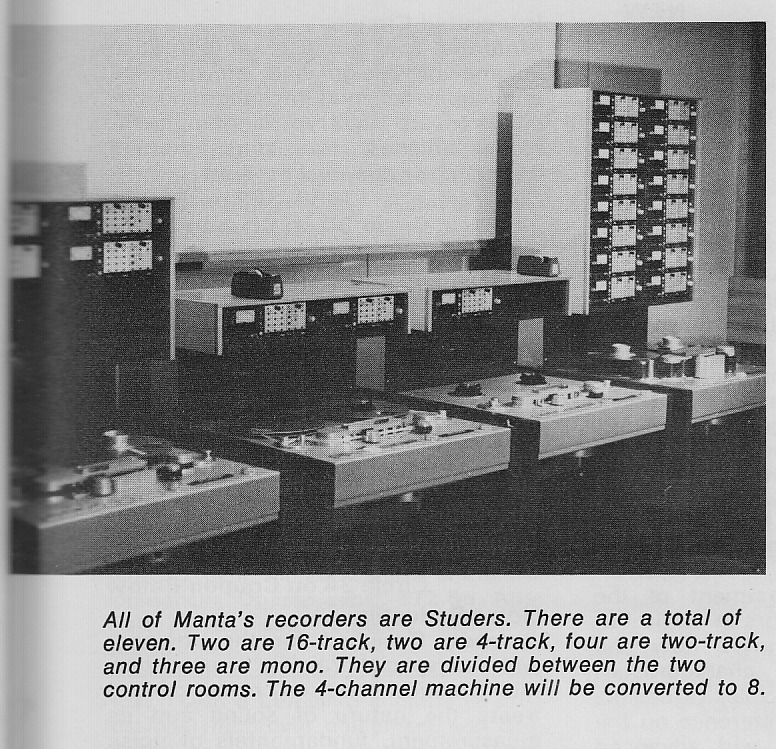

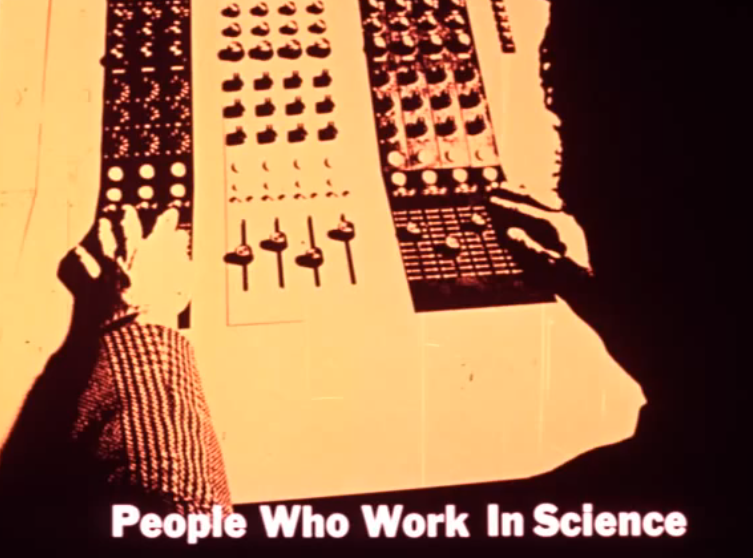

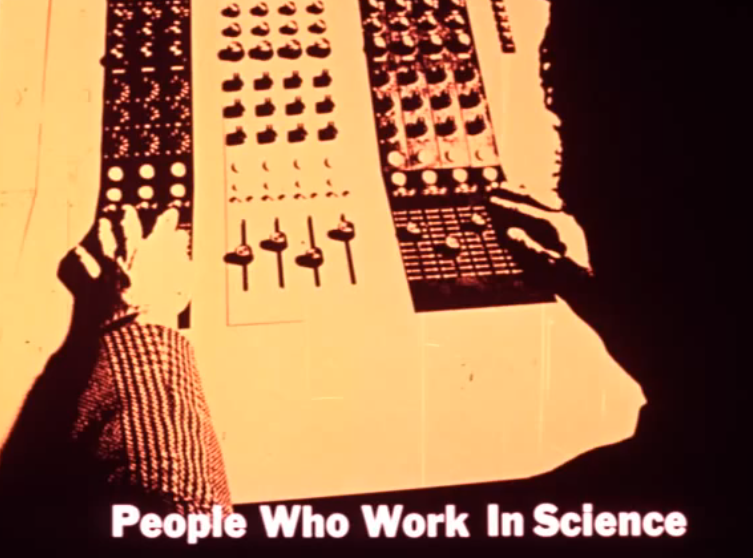

T. Fine: “In 1972, Guidance Associates (still in business in Mt. Kisco NY) produced a filmstrip centered around RSS sound engineer Bill Brueckner. Bill’s work day described in the filmstrip involved putting the soundtrack together for a Cheetos TV commercial. The filmstrip shows images of a 1970’s sound-for-picture studio in action. Brueckner is shown working in two separate studios at Reeves. The studio where the commercial was made was the more modern studio. The console appears to be custom-made, probably using Langevin faders and internal parts. The second studio shown, where Brueckner is recording a voice-over later in the filmstrip, is older. Visible there are a Fairchild full-track tape machine, an Ampex 300 full-track, plus a very old mono console.”

T. Fine: “In 1972, Guidance Associates (still in business in Mt. Kisco NY) produced a filmstrip centered around RSS sound engineer Bill Brueckner. Bill’s work day described in the filmstrip involved putting the soundtrack together for a Cheetos TV commercial. The filmstrip shows images of a 1970’s sound-for-picture studio in action. Brueckner is shown working in two separate studios at Reeves. The studio where the commercial was made was the more modern studio. The console appears to be custom-made, probably using Langevin faders and internal parts. The second studio shown, where Brueckner is recording a voice-over later in the filmstrip, is older. Visible there are a Fairchild full-track tape machine, an Ampex 300 full-track, plus a very old mono console.”

T. Fine: “The filmstrip (with accompanying LP) was part of a set titled “People Who Work In Science,” probably aimed at middle school aged kids. I found a mint-condition copy about 10 years ago; I assume a set was sent to my father since the ‘Sound Engineer’ strip was done at Reeves. I immediately transferred the LP, and eventually found someone to scan the filmstrip for me. Bill Wray, head of the AES Historical Committee and a retired Dolby exec, married the sound to the picture. He started out with side A of the LP, which has mid-range pitch manual-advance tones. He assembled the piece in Final Cut Pro and then laid over the side B audio, which had low-frequency auto-advance tones which I had notched out. We just recently finished it, got permission from the original publisher and posted it to the AES’ YouTube page. Thanks to Peter Haas for scanning the filmstrip and Jay McKnight for doing very good Photoshop cleanup on the images (the filmstrips were manufactured on that type of film stock that fades out to red over time).”

*************

*******

***

And that’s pretty much all I have been able to uncover regarding Reeves Sound Studios. Hazard Reeves himself was a very public figure with a great number of technologies and awards to his credit; he started sixty companies in his lifetime, won an Oscar, helped introduce the blender to American kitchens, and owned a major audio-tape manufacturing facility just a stones-throw away from where I grew up in Danbury Connecticut.

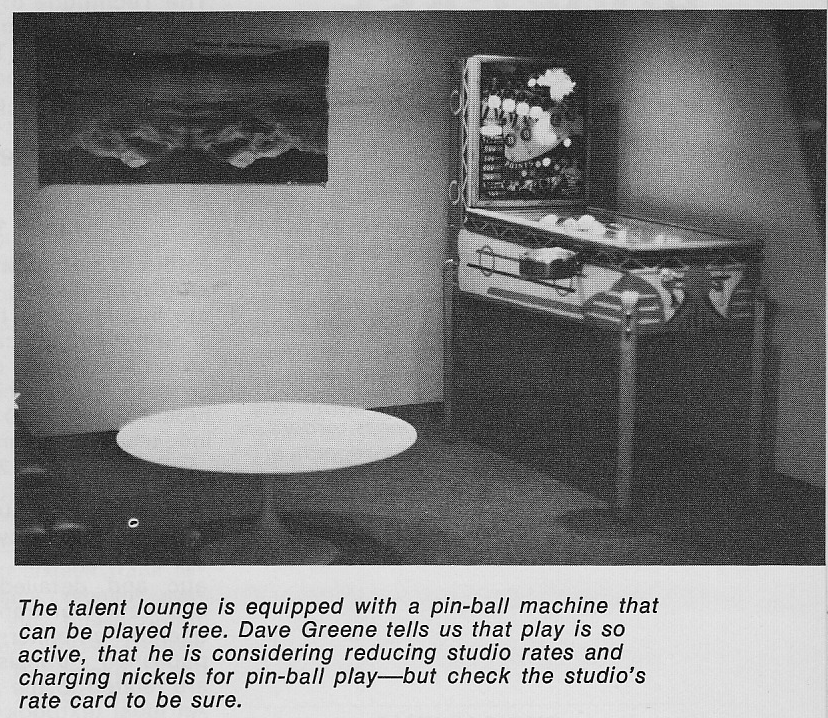

Above: a 7″ reel of consumer-grade Reeves Soundcraft audiotape, manufactured on Great Pasture road in Danbury CT.

Above: a 7″ reel of consumer-grade Reeves Soundcraft audiotape, manufactured on Great Pasture road in Danbury CT.

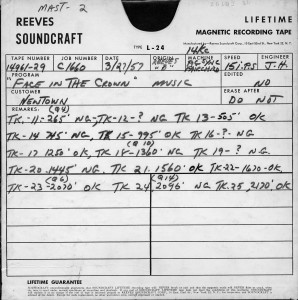

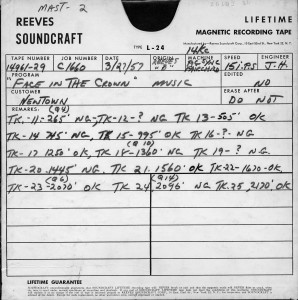

Above and left: a 10″ reel of industrial-grade Reeves audiotape. T. Fine: “Interesting data on the rear of the box. This was sound-for-picture music work done at Reeves Studio B. The engineer was “J.H.”, most likely Jack Higgins, the engineer who made most of the Riverside jazz records at Reeves. You see notes for “Pic-Sync Fairchild,” meaning the tape was recorded on one of the studio’s Fairchild tape machines using the Pic-Sync system, which used a tone modulated at 14kHz to sync with motion-picture cameras and projectors. I can’t fully interpret the take sheet, but it looks like they were scoring to picture, with timing marks indicating footage from the film projector.”

Above and left: a 10″ reel of industrial-grade Reeves audiotape. T. Fine: “Interesting data on the rear of the box. This was sound-for-picture music work done at Reeves Studio B. The engineer was “J.H.”, most likely Jack Higgins, the engineer who made most of the Riverside jazz records at Reeves. You see notes for “Pic-Sync Fairchild,” meaning the tape was recorded on one of the studio’s Fairchild tape machines using the Pic-Sync system, which used a tone modulated at 14kHz to sync with motion-picture cameras and projectors. I can’t fully interpret the take sheet, but it looks like they were scoring to picture, with timing marks indicating footage from the film projector.”

*********

***

Above: Hazard Reeves with a Cinerama 6-channel sound-head circa 1948

Above: Hazard Reeves with a Cinerama 6-channel sound-head circa 1948

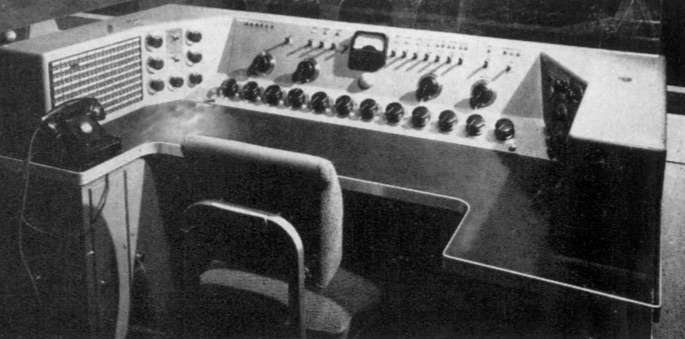

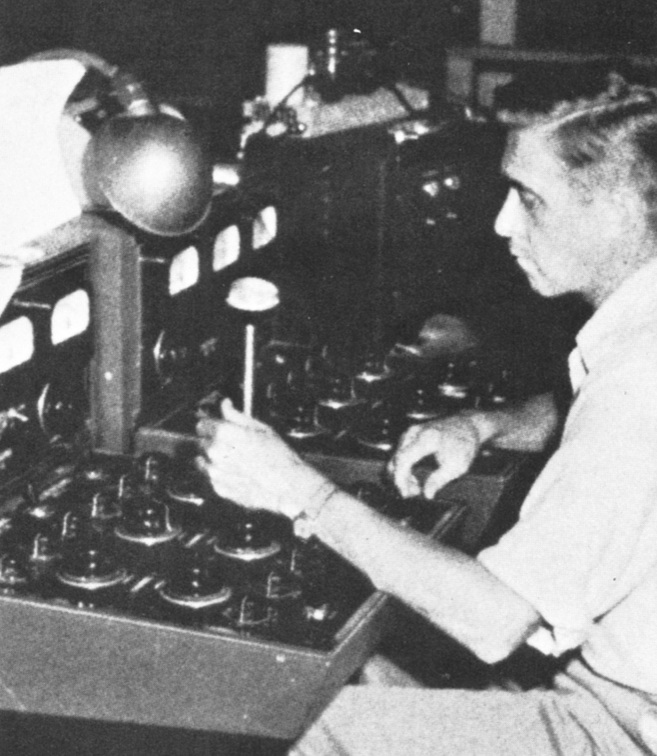

Above: an unknown audio engineer operates the 6-channel playback console at a Cinerama movie theater circa 1952.

Above: an unknown audio engineer operates the 6-channel playback console at a Cinerama movie theater circa 1952.

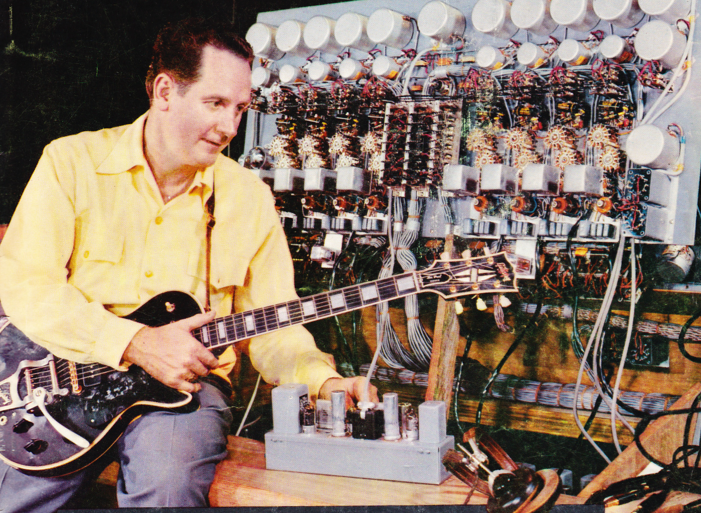

The 3-camera, 3-projector, 6-channel surround-sound film format known as Cinerama has proven to be Hazard Reeves’ principal legacy. There is a ton of information online regarding this far-ahead-of-its-time quirk of film history, so I won’t repeat any of that here. But I would like to point out how interesting it is that although Reeves possessed the technology to create 6-track magnetic audio masters as early as 1948 (as evinced by the image above), he did not chose to apply this technology to music recording. We can only assume that this was because the musical aesthetics of the day simply did not require it. In 1948, live music was still the paradigm of musical-sound; there was evidently not sufficient demand to build a console and studio workflow that would allow for multitracking and overdubbing until a decade later, ever though the actual recording technology evidently existed. This begs the question of what technologies we currently posses that could be put to the service of creating entirely new musical aesthetics, but which we are dismissive of, or simply blind to.

Nonetheless, Reeves’ diversified and energetic ventures reveal a man who boldly took advantage of the emerging technologies of his era to develop better and more effective communication products. Reeve’s assessment of the relation between media form and media message is stated quite eloquently in this passage he wrote in the November 1982 SMPTE Journal:

Show, don’t tell. That’s the message here. And ultimately this is remains the critical factor in creating meaningful artwork and communication, regardless of the tools and technologies used to produce it.

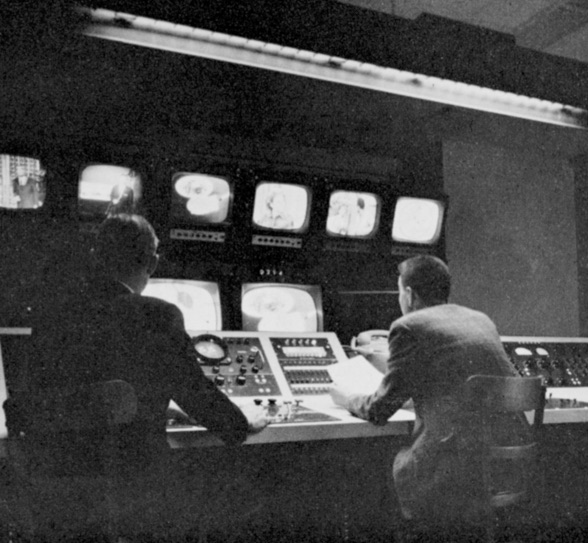

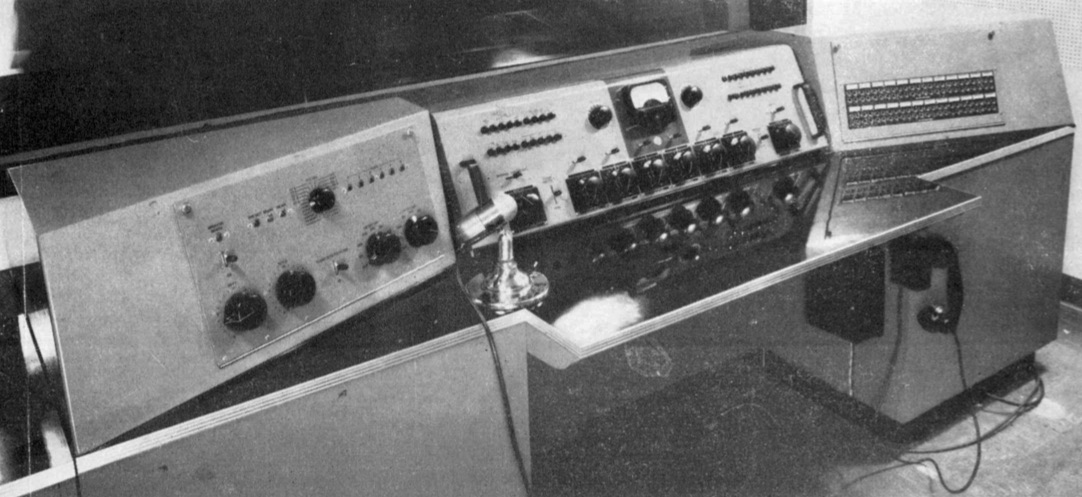

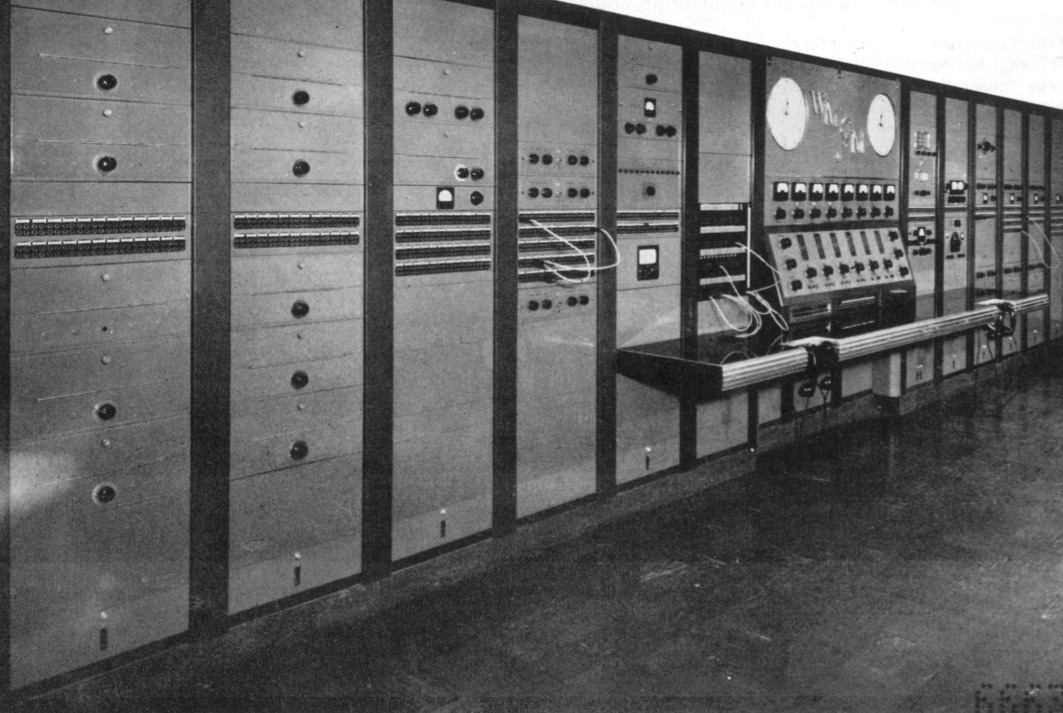

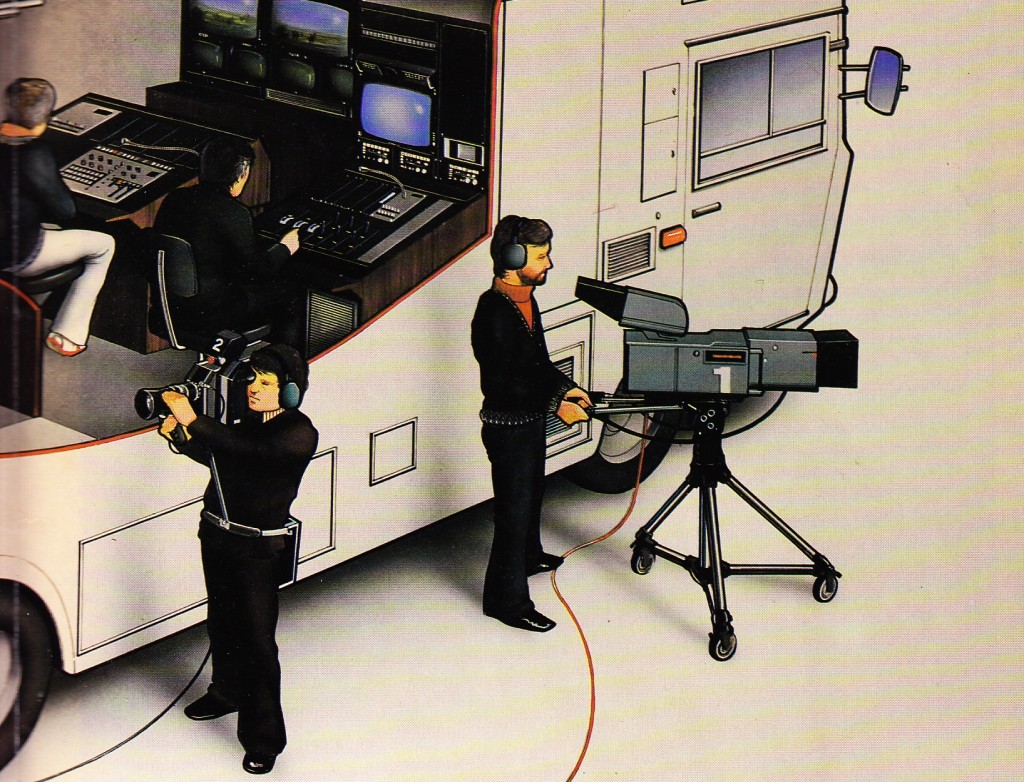

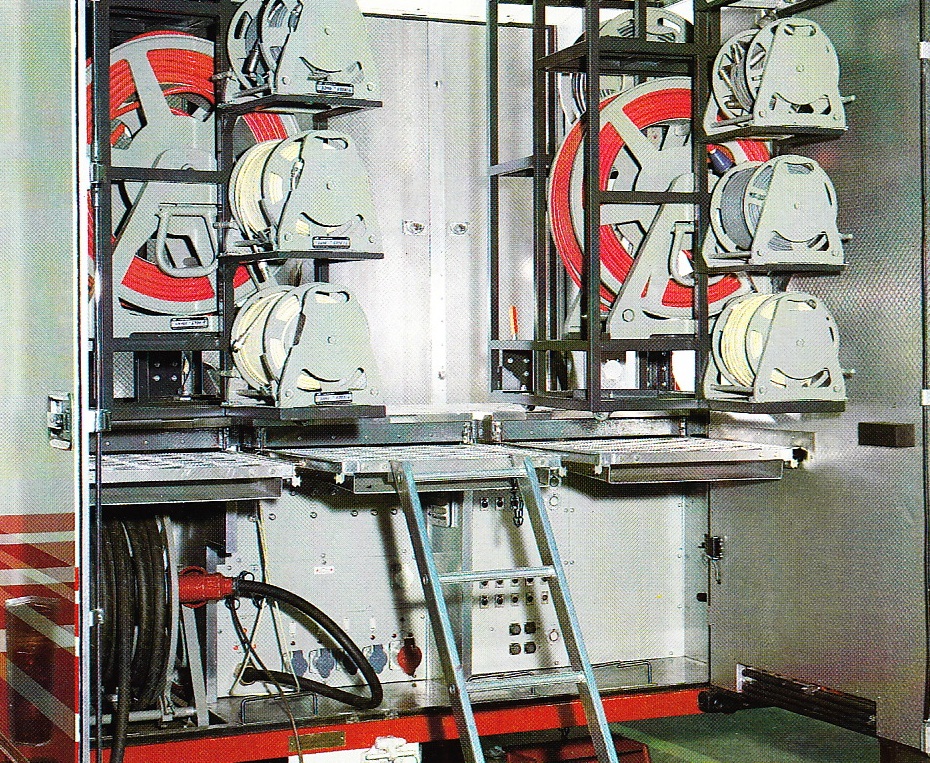

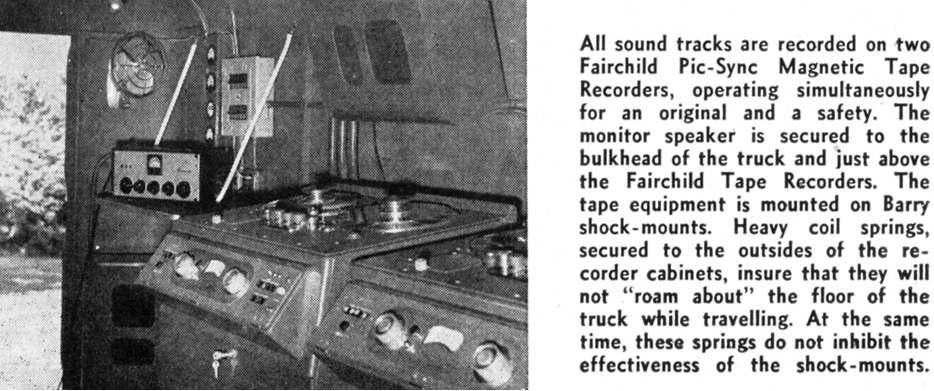

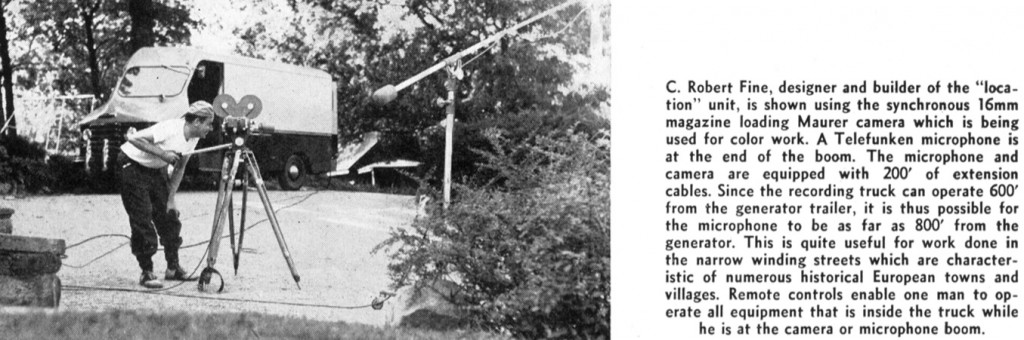

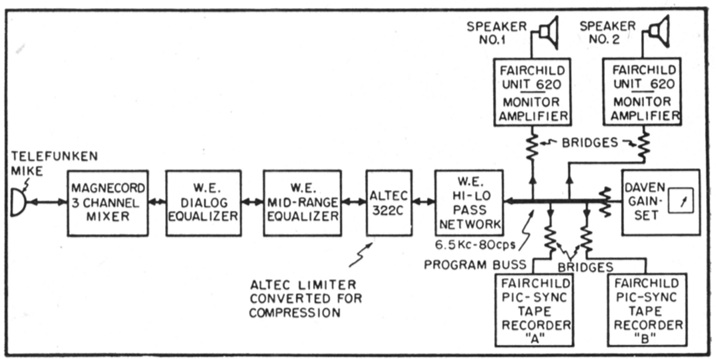

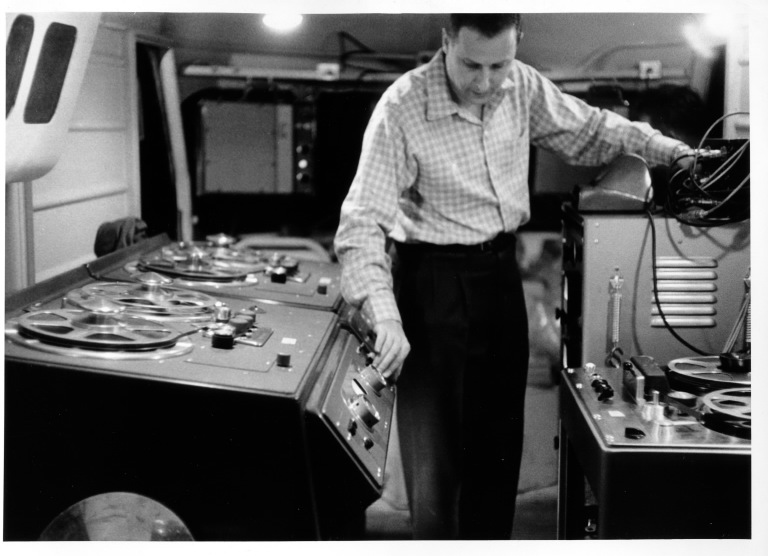

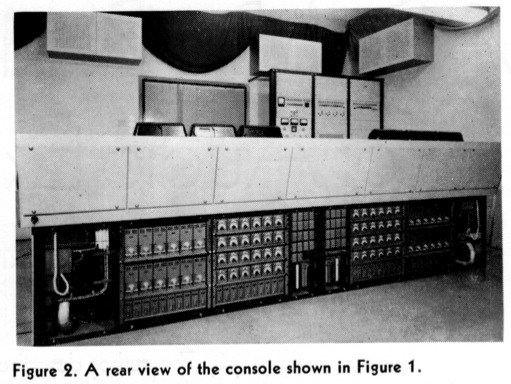

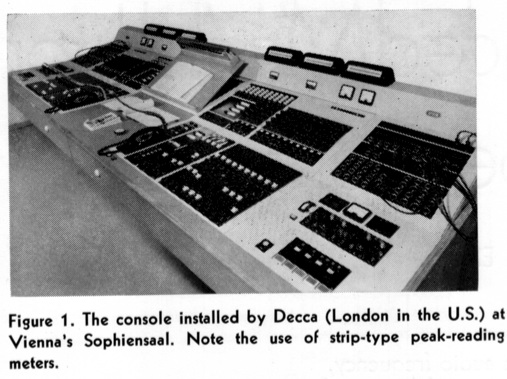

Courtesy Tom and John Fine is this fascinating 14pp 1962 article on the then-state-of-the-art television operations at Reeves Sound Studio.

Courtesy Tom and John Fine is this fascinating 14pp 1962 article on the then-state-of-the-art television operations at Reeves Sound Studio.